First rule: Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing. All they do is show you’ve been to college. ― Kurt Vonnegut

By PJ Parrish

I had been storing this blog to run around Thanksgiving, but John D. MacDonald forced my hand this week, so I’m posting early. I want to take a moment to acknowledge the books and thank the authors who have helped me along the way.

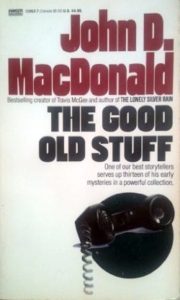

Recently, I was asked by a writer friend Don Bruns to contribute to an ongoing series that has been running in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune called “John D and Me.” Cool beans, I thought, since other contributors included Stephen King, Lee Child, Dennis Lehane, Heather Graham, JA Jance, David Morrell…the list went on and on. Click here to read my article. Don’t worry…it’s short. I chose to write about MacDonald’s short stories because, truth be told, I hadn’t read many of the guy’s novels back then. But I had found a yellowed dog-earred copy of his short story collection The Good Old Stuff in a used book store, and at that time, I was struggling mightily to write my first short story.

Actually, it wasn’t my first. My first short story was way back in eighth grade. I was an inattentive student, but I had a lovely teacher Miss Gentry, who made us write a short story. The only touchstones in my little life at that point were The Beatles and my only dream was to run away to London. So I wrote about a lonely cockney boy who painted magic pictures. It was called “The Transformation of Robbie.” I got an A on it.

Miss Gentry

After class, Miss Gentry pulled me aside and said, “you should be a writer.” Twenty-five years later, I dedicated a book to her.

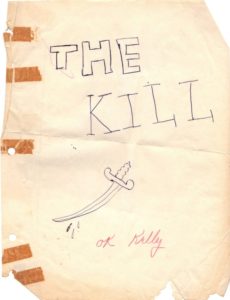

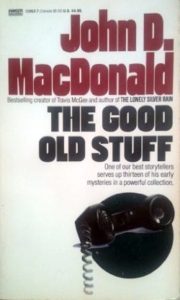

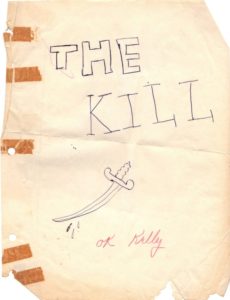

It should be noted that my sister and future co-author Kelly was also churning out short stories in those days. Her most notable effort was called “The Kill.” It was about a serial killer who knocks off The Beatles, one by one. We joke now that nothing much has changed: She still likes to write the gory scenes, I like doing the psychological stuff. I don’t have my early efforts, but she kept hers – see photo below right for the stunning cover she designed at age 11.

Fast forward to 2005. I am trying to write a story for the Mystery Writers of America’s anthology, edited by Harlan Coben. In addition to the big-name writers the editor invites, the anthology holds out 10 spots for blind submissions from any MWA member. I had a good idea for my story and four published mysteries under my belt. But I couldn’t get a bead on the short story’s special formula. What came so easy at age 14 wasn’t coming so easy at age 54.

So I cracked open The Good Old Stuff. Maybe it was because I had been reading Cheever and Chandler and was getting intimidated. But MacDonald made it look effortless. His stories, culled from his pulp magazine career, had an ease and breeze as fresh as the ocean winds. I realized I had been fighting an undertow of expectations, so I flipped over on my back and floated. The words flowed, the story formed. My first adult short story, “One Shot” got picked for MWA’s anthology Death Do Us Part. It was the second proudest moment of my writing life, right after Miss Gentry’s A.

Writing about MacDonald this month got me thinking about the debts I owed to other writers. Here are a couple I should thank:

E.B. White. Charlotte’s Web remains my favorite book of all time. I love it as pure story, but it taught me a very valuable lesson that all novelists should take to heart: Sometimes, you just have to kill off a sympathetic character.

Joyce Carol Oates. Lots of lessons from this woman about productivity and having the courage to write outside the boundaries of whatever box they try to put you in. But one book of hers had a huge impact on me — Because It Is Bitter and Because It Is My Heart. From this murky violent story of murder and race, I learned about the power of ambiguity, about the need to leave room in a story for the reader’s imagination to breath, to resist the urge to tie everything up in a neat bow. Also, she just makes me want to write with more metaphoric power. Check out her opening paragraph:

“Little Red” Garlock, sixteen years old, skull smashed soft as a rotted pumpkin and body dumped into the Cassadaga River near the foot of Pitt Street, must not have sunk as he’d been intended to sink, or floated as far. As the morning mist begins to lift form the river a solitary fisherman sights him, or the body he has become, trapped and bobbing frantically in pilings about thirty feet offshore. It’s the buglelike cries of the gulls that alert the fisherman – gulls with wide gunmetal-gray wings, dazzling snowy heads and tails feathers, dangling pink legs like something incompletely hatched. The kind you think might be a beautiful bird until you get up close.

Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. I still think about this story years after I read it. From it, I learned about spare writing and especially the power of one indelible image. Michael Connelly talks about this, too, about how one gesture, word or image can have so much more impact than an avalanche of description. Connelly talks about how he wrote about a cop who seemed the paragon of cool, how nothing about the horrors of his job seemed to bother him. Except for one telling detail – the stems of his glasses were chewed down to the nubs. In The Road, the image I can’t get out of my head, the one thing that stands in my mind as the symbol of post-apocalyptic survival, is canned peaches.

In the story, a man and the boy discover a cache of supplies in an abandoned farmhouse. Among them is canned peaches. Yes, it’s a delicacy in a time of starvation, but McCarthy also uses it as a symbol marking the split in the world between the fruit-eating “good guys” and the cannibalistic “bad guys.” Here’s an exchange between man and boy:

He pulled one of the boxes down and clawed it open and held up a can of peaches.

“It’s here because someone thought it might be needed.”

“But they didn’t get to use it.”

“No. They didn’t.”

“They died.”

“Yes.”

“Is it okay for us to take it?”

“Yes. It is. They would want us to. Just like we would want them to.”

“They were the good guys?”

“Yes. They were.”

“Like us.”

“Like us. Yes.”

“So it’s okay.”

“Yes. It’s okay.”

They ate a can of peaches. They licked the spoons and tipped the bowls and drank the rich sweet syrup.

I can’t eat canned peaches anymore because of this. I want to cry just thinking about.

Neil Gaiman. When I was working on our latest book She’s Not There, I needed to find just the right children’s book that resonated with my adult heroine. It was happenstance that I found Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book. It follows the adventures of a boy named Bod after his family is murdered and he is left to be brought up by a graveyard. Which metaphorically is what happened to my heroine. I just started Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane, which, like my own book, is about the fragility of memory. I think what I am learning from Gaiman is the need to be original, to not follow the pack, to be true to yourself as a writer. He sums it up in this quote:

Start telling the stories that only you can tell, because there’ll always be better writers than you and there’ll always be smarter writers than you. There will always be people who are much better at doing this or doing that – but you are the only you.

David Morrell. Several years ago, David was the guest of honor at our writers conference SleuthFest here in Florida. This talented teacher, prolific writer, and editor of the anthology Thrillers: 100 Must Reads, and creator of Rambo no less, had tons of great advice. But here is the single line that impacted me as a writer.

Find out what you’re most afraid of, and that will be your subject for your life or until your fear changes.

David credits this lesson to another writer Phillip Klass (pen name William Tenn) who told David that all the great writers have a distinct subject matter, a particular approach, that sets them apart from everyone else. The mere mention of their names, Faulkner, for example, or Edith Wharton, conjures themes, settings, methods, tones, and attitudes that are unique to them. How did they get to be so distinctive? By responding to who they were and the forces that made them that way. And all writers are haunted by secrets they need to tell. David talks about this in his book The Successful Novelist: A Lifetime of Lessons about Writing and Publishing. Click Here to read the first chapter.

And last but not least…

Unamed Romance Novel. I read this eons ago as part of my education back in the days when I thought I was going to make a million bucks writing for Harlequin. This novel (I won’t use the title here) taught me perhaps the most valuable lesson of all, one that every writer – published or un – should take to heart. Here is the line from the book that did it:

She sat on the sand on Miami Beach and watched the sun sink slowly into the ocean in a blaze of orange and pink.

When I read that line, I threw the book across the room. But then I picked the book up and put it on my shelf, where it still sits today. (Well, on my bathroom shelf). Because this book taught me that no matter how brilliant your metaphors, how original your story, how beguiling your prose, how deep your unexplored fears, if you have the sun setting in the east, nothing else is gonna work.

So who were your teachers, what were their books, and what did you learn?