Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

By Debbie Burke

@burke_writer

Welcome to another Brave Author who’s submitted a first page for critique. The story is untitled so I used the name of the likely main character.

Please read and enjoy then we’ll discuss.

~~~

2 years ago, Port of Chicago

“All positions report in,” Special Agent Jonas Stone released the transmission button on the communicator attached to his wrist.

“Sierra 6, good to go,” the team leader of the Special Weapons and Tactics Team sounded off from their tactical vehicle.

“Sierra 3, on station and sighted in,” the sniper team responded.

“Sierra 5, off the shore and set up in case they try to break out of the port,” the Marine Unit called in.

The rest of the perimeter posts completed their check in.

“That’s all of them,” Jonas looked over at his partner in the passenger seat of their SUV. Special Agent Michael Lock had been with Jonas since the beginning of their time together with the Secret Service. These last twelve years Mike had become like a brother, something Jonas missed from his time in the military.

“Let’s just hope everything is going as planned for Eddie,” Mike said, the worry etched on his face. “I don’t want to face the wrath of Linda if something happens to him.”

Jonas shook his head thinking about the firecracker that was Eddie’s wife. The old adage of Murphy’s Law, “Anything that can go wrong will go wrong,” reared its ugly head right from the beginning of the operation. The transmission wire set up on their snitch, or confidential informant as Mike liked to correct Jonas when talking about Eddie, completely malfunctioned. Mike had a soft spot for Eddie, more so than even Jonas.

“What time is it?” Jonas asked.

“2200 hours.”

Eddie has always been reliable. When it came to snitching, he was the best Jonas’ had ever worked with, the gold standard. Some of the biggest cases in the Chicago Field Office, dealing with everything from counterfeit U.S. currency to child pornography cases, were thanks to Eddie. Jonas and Mike looked out for him and made sure he got paid handsomely for his contributions over the years.

“It’s been over an hour, and we haven’t heard any word from him,” Jonas pressed, knowing the success of the operation will come down to the signal from Eddie.

This wasn’t just another case for Jonas. This was personal.

“It’ll work out, Jonas,” Mike seemed to pick up on his anxiety. “Eddie will come through, he always does. Today, we will take down the bastards that killed Jade.”

Jonas’ eyes misted over, and he couldn’t speak. He had investigated this human smuggling ring for the last six months. They had been responsible for his daughter’s disappearance and heinous death, but the evidence was lacking. The case finally got a shot in the arm thanks to Eddie. He had provided information that there was a vessel in one of the harbors of the Port of Chicago that was going to be loaded with two CONEX boxes containing local kidnapped girls bound for New York City.

~~~

Okay, let’s get started.

2 years ago, Port of Chicago – This is evidently a chapter heading for what appears to be a prologue. It suggests within a few pages the story will jump forward to present day.

Some readers love prologues, some hate ’em. I don’t care either way. But consider deleting “2 years ago” and just use “Port of Chicago.” Then, if the story does jump forward, the heading of the next section could be, “Two years later.”

This story is about human trafficking and features a Secret Service team poised to arrest perpetrators in the Port of Chicago. The subject is timely and compelling, making it a good choice for what sounds like a thriller or police procedural.

Featuring the Secret Service as the lead agency is another good choice because it hasn’t been used as frequently as the FBI and other police agencies. That makes it stand out among other books in the genre, especially if the Brave Author adds fresh insights to the Secret Service’s particular duties, like counterfeiting and child pornography, that are also mentioned.

The Port of Chicago is a dramatic setting because it offers plenty of dangerous backdrops for action to unfold.

I had to look up CONEX boxes but that’s okay because the use of a specific type of shipping container lends authenticity.

When balancing between too much description vs. not enough, I believe it’s better to err on the side of not enough, especially at the beginning of the story, to not slow the action. However, BA might consider adding more setting details a bit later to bring the locale to noisy, colorful, smelly, vivid life.

BA selected an effective point to begin the story. The agents are in the middle of a tense operation, in media res, and they have a problem—their most reliable snitch hasn’t been heard from. The success of the mission rests on him and his wire isn’t working. The stakes are upped even higher because the villains are responsible for the death of the daughter of the POV character, Special Agent Jonas Stone.

Good job setting up the story problem and stakes!

A small aside: names that end with “s” can be inconvenient. You have to decide if the possessive is Jonas’s or Jonas’ (either is correct) then remain consistent. Also, it can lead to unneeded apostrophes such as the best Jonas’ had ever…

One last consideration: this might eventually become an audiobook. Jonas Stone is a mouthful for the narrator.

This doesn’t mean BA shouldn’t use the name, simply to consider it can add small problems.

Let’s look at characterization. Jonas Stone has been partnered for 12 years with Mike Lock and they are like brothers. Jonas was formerly in the military. Jonas cares about his “snitch” Eddie but not as much as Mike does. Jonas lost his daughter Jade to the traffickers they are now targeting.

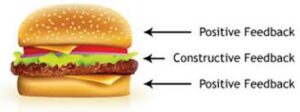

This is all good background information, but it is TOLD to the reader, rather than SHOWN. Showing engages the reader more with Jonas.

Use the first eight lines then try reworking their conversation. Here’s a sample of SHOWING (in blue) more than TELLING.

“Everyone’s checked in.” Jonas glanced at Mike Lock, his partner of twelve years, sitting in the passenger seat of their unmarked Secret Service SUV. Jonas gnashed his chewing gum. “Still, this operation has Murphy’s Law written all over it.”

“Tell me about it,” Mike answered. “If something goes wrong, I don’t want to be the one to explain to Eddie’s wife that his wire didn’t work.”

“Yeah, he’s helped us close a lot of cases. Best snitch I ever worked with.”

Mike looked down his nose. “That’s confidential informant.”

“All right, all right, I get it,” Jonas snapped then regretted his sharpness.

Mike was right—some of the biggest cases in the Chicago Field Office, everything from counterfeit U.S. currency to child pornography cases, were thanks to Eddie. Jonas and Mike made sure he was paid well, and he always delivered.

After a few seconds of silence, Mike’s elbow nudged Jonas’s shoulder. “You OK, buddy?”

“Yeah.” No, Jonas wasn’t OK. This case was personal. These same traffickers had murdered his daughter, Jade.

“Eddie will come through for us. He always does.” Mike cuffed Jonas’s arm. “Today we’re gonna get the evidence to take the bastards down. For Jade.”

Same info but it’s SHOWN with dialogue, tone of voice, facial expressions, gestures, and internal monologue.

To ramp up an already-tense situation, consider adding a ticking clock. For instance:

Jonas asked, “What time is it?”

“Twenty-two hundred hours.”

“Wonder how long those kidnapped girls can survive in CONEX containers. Aren’t they air-tight?”

A few typos and minor nits:

“2200 hours.” – Spell out numbers in dialogue: “Twenty-two hundred hours.”

Eddie has always been reliable. – Change of tense. Eddie had always been reliable.

…the best Jonas’ had ever worked with – delete apostrophe.

…word from him,” Jonas pressed, – pressed isn’t a normal verb to describe speech. Maybe stick with said but add a physical gesture like: Jonas clutched the steering wheel.

…the operation will come down to the signal from Eddie. – change to the operation would come down.

Brave Author, you chose a timely crime with high stakes. The story starts with action, tension, and suspense. Putting your characters in the Secret Service offers a chance to explore their special duties that aren’t widely known to the public—a value-added bonus for the reader.

The main character has an urgent, driving need to put his daughter’s killers behind bars. If BA moves a little deeper into Jonas’s head and heart, the reader feels his loss more intensely and roots harder for his success.

This is a strong start that can be improved with minor tweaking. Good work and good luck with this, Brave Author!

~~~

TKZers: What suggestions do you have for the Brave Author? Would you turn the page?

~~~

Deep Fakes are illusion but death is real.

Debbie Burke’s new thriller Deep Fake Double Down launches on April 25, 2023. Available for pre-order now at Amazon.

I’m pleased to have Steve “Captain” Marvel, the narrator of my Mapleton Mystery series, as my guest at The Kill Zone today. We’ve been working together for eight novels and a three-novella bundle and since I’m virtually clueless about how someone works with voice rather than fingers, I asked if he’d share a bit about himself and his process. He said he’d check in from time to time, so if you have any questions for him, ask away.

I’m pleased to have Steve “Captain” Marvel, the narrator of my Mapleton Mystery series, as my guest at The Kill Zone today. We’ve been working together for eight novels and a three-novella bundle and since I’m virtually clueless about how someone works with voice rather than fingers, I asked if he’d share a bit about himself and his process. He said he’d check in from time to time, so if you have any questions for him, ask away.

What’s the favorite part of the job (not counting getting paid!)

What’s the favorite part of the job (not counting getting paid!)