by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

There is a publishing industry. And there is a publishing world.

There is a publishing industry. And there is a publishing world.

The Big 5 publishers, along with the Medium However Many, form the industry.

All of them, plus every self-publishing author, form the world.

Here in 2017, what does that world look like? Your humble correspondent now takes his shot.

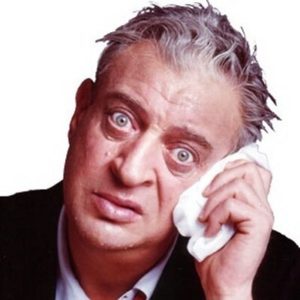

Self-Publishing is Not Rodney Dangerfield

Back around 2010-2011, the internet was aflame with screeds arguing all sides of the self-publishing boom. Such jeremiads have mostly disappeared. But every now and then, like a California aftershock, we get a fulmination that rattles the furniture.

One such appeared recently in HuffPo, wherein author Laurie Gough referred to the self-publishing enterprise as “an insult to the written word.” As of this morning, the piece has well over 600 comments, and at least one solid “fisking.” What a stroll down Memory Lane! It was like the good old Joe Konrath-Barry Eisler blogosphere of yore.

Ms. Gough believes that “gatekeeping” is essential for the consumer. “Readers expect books to have passed through all the gates, to be vetted by professionals. This system doesn’t always work out perfectly, but it’s the best system we have.”

Is it? Sarah Nelson, Executive Editor at Harper Collins, seems to think so:

There will always be a market for good writing and storytelling, whatever the format, and there are always going to be “gatekeepers,” no matter how much people complain about them. In fact, the more self-published stuff that’s out there, the more imprints, the more books, the more regular people (i.e. people who buy books) are going to need a filter, a curator, a gatekeeper. Nobody can read everything, after all: people still want to hear what’s the best of the bunch.

Methinks this does not reflect how readers actually decide to plunk down their discretionary income. Almost always it’s by some form of word-of-mouth that a book is purchased. These days, word-of-mouth is not only by way of a friend, but also reader reviews on Amazon and Goodreads.

In other words, readers are the gatekeepers.

Besides, attempts to form some sort of new, official gatekeeping locale have been going on for years, without success. Remember Bookish? It started off as a joint venture between the (then) Big 6 publishers to create an Amazon-style footprint on the internet. This was back during the industry fight over Amazon’s increasing dominance, and before the Department of Justice stepped in to stop the brouhaha. In any event, Bookish did not catch on. There was simply not enough incentive or reason to latch onto a new form of “approval.”

Self-publishing continues to get a few slings and arrows from the establishment, but the force of the blows is largely spent. “With my dog,” Rodney Dangerfield once said, “I don’t get no respect. He keeps barking at the front door. He doesn’t want to go out. He wants me to leave.”

Self-publishing continues to get a few slings and arrows from the establishment, but the force of the blows is largely spent. “With my dog,” Rodney Dangerfield once said, “I don’t get no respect. He keeps barking at the front door. He doesn’t want to go out. He wants me to leave.”

Well, self-publishing authors aren’t leaving. And those who keep producing and growing as writers, and who take a business-like approach, will fare nicely.

The Future of Print

Back in 2013 you could find fields of blooming blogsters predicting the imminent demise of traditional print publishing. (I was not one of them, likening trad-pub to the fighter who would not go down, Jake “Raging Bull” LaMotta.)

Last year Publishers Weekly wrote a story about the Codex Group’s April, 2016 survey of booksellers. The main finding was that “e-book units purchased as a share of total books purchased fell from 35.9% in April 2015 to 32.4% in April 2016. The Codex survey includes e-books published by traditional publishers and self-publishers and sold across all channels and in all categories.”

What was the cause of the decline (or stagnation, if you’re a half-full kind of person)? It might be “digital fatigue,” especially among the young—the future book buyers.

[T]hough book buyers stated they spent almost five hours of daily personal time on screens, 25% of book buyers, including 37% of those 18–24 years old, want to spend less time on their digital devices. Since consumers almost always have the option to read books in physical formats, they are indicating a preference to return to print … Overall, 14% of book buyers said they are now reading fewer e-books than when they started reading books in the format, and 59% percent of those who said they are reading fewer e-books cited a preference for print as the main reason for switching back to physical books. The share of print books purchased was also the highest among the heaviest screen users, the so-called digital natives, ages 18–24 (83%), and lowest (61%) among 55-to-64-year-olds.

That’s a bit of amazing, isn’t it? A few years ago all the old codgers were thinking this younger generation was going to be all digital, all the time. Apparently, the trend is the other way! Don’t those Millennials know how to listen to us?

And in another bit of print-preservation news, one of the original indie firebrands, Joe Konrath, announced a print-only deal with Kensington:

I’ve always known that I’m leaving money on the table because my books aren’t in brick and mortar stores. There are a whole lot of readers who shop at bookstores, airports, department stores, and convenience stores, and I’m not available in those outlets. My POD titles are $13-$17, which is pricey compared to my $4.99 ebooks. Wal-Mart won’t ever carry me. Neither will B&N.

This Kensington deal will let me reach an audience I haven’t reached since 2009.

So is this a portend of things to come for self-pubbed authors?

Kensington has shown themselves to be nimble and forward-thinking. I have yet to see any evidence that the Big 5 are smart enough to try something like this, save for that big Hugh Howey deal years ago. Writers waited for more opportunities like that (me included), and none happened.

It will indeed be interesting to see how this plays out. Kensington specializes in mass market editions, a segment of the industry that has been in steady decline. If Kensington can figure out a way to make it work for Konrath, maybe others will follow…but only those with significant ebook success, a la Joe.

Add one more datum, from the aptly named “Data Guy” (the mastermind, with Hugh Howey, behind the Author Earnings Reports). As quoted by Mr. Porter Anderson in the new Digital Book World white paper, Mr. Guy states, “Adult fiction sales in the US are nearly 71 percent digital now, and that is also the category where indie sales have made the deepest inroads: today, 30 percent of all US adult fiction book purchases are of titles self-published by indie authors.”

When it comes to fiction, then, E is eating away at P. And it is voracious.

And don’t let us forget about the fastest-growing medium for “reading” books: audio. According to one source, audio book downloads increased by a whopping 38.1 percent in 2015. An executive of Audible, Inc. is quoted in the story thus: “Audible members globally listened to 1.6 billion hours of audio content in 2015 (up from 1.2 billion in 2014).”

So A now encroaches on both E and P. That’s the alphabet soup of current publishing.

However, print will hang in there. As one editor told me, “Flat is the new up.” And there’s some good cheer for print in the mini-boom of independent bookstores. As Borders closed down and Barnes & Noble cut back, mom-and-pop bookstores started springing up. According to one report, 550 indie bookstores have opened since 2010. That makes me happy.

The Rise of Amazon Publishing, and How it Affects Indies

Amazon continues to expand its own imprint publishing program. They now have thirteen (13) imprints, ranging from mystery & suspense (Thomas & Mercer) to StoryFront, a venue for short fiction. Wow.

This expansion has been the subject of interest to many pure indie writers, who have reported a downward trend in their sales. John Ellsworth, for example, a bestselling legal thriller authors, wonders if APub is the major reason behind this decline.

Well, APub is an arm of the world’s largest bookstore, and therefore it makes sense that it would use the power of its algorithms to feature titles it publishes. It’s like front-of-store placement.

Amazon Publishing is turning out a high-quality product, and so will continue to expand. Heck, Amazon is even opening up physical bookstores to shelve them!

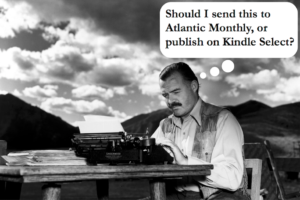

Writers, as the corks atop the roiling sea of change, will continue to adjust. Indies are always experimenting with things like Kindle exclusivity versus “going wide.” There are also scads of startups who want to partner with authors for publication and distribution. All I can say to that is, caveat scriptor! Do your homework before signing over your life’s work. For while there are top-notch companies like Brach Books, there is also a cautionary tale in the shuttering (and withholding of royalties) by AllRomance.

Are We All Part of The Gas Lamp Industry Anyway?

The larger question is whether book publishing itself is in its last phase as a human enterprise. There was a need for gas lamplighters 120 years ago. Electricity killed that need. Human beings were out of jobs. Fast food franchises are moving to ordering kiosks, with more jobs lost.

Will the same thing happen to authors when AI starts churning out books? What Patterson does with co-writers now, AI will do by itself, a million times faster and perfectly tailored to the various market niches.

Hugh Howey predicts that AI will become “the holy grail for readers, the end of writing as a profession, and I give it anywhere from 50 – 200 years.”

Entire novels will be written from scratch by machines, a million novels spurting out in the blink of an eye, and they will be tailored to individual readers, win major awards, and be as sublime and moving as anything we’ve ever read before. We balk at the idea now, but just as manually driving a car will seem insane one day (unless on a closed track by daredevils with death wishes), a handwritten novel will also seem bizarre. Why do with long division what a calculator on our phone can do for us? Sure, people will still write, but very few will read these works. And the process will happen so gradually that hardly anyone will understand what has happened.

Sure, machines will try to take over. We’ll Sarah Connor them! And we’ll keep writing. Because what we do. Never despair over trends. We are the storytellers!

With apologies to Dylan Thomas, let me adapt his most famous poem for our purposes:

Do not go gentle onto that good page,

True writers burn and rave at gloomy news;

They type, and never think to disengage.

They know it’s hard to make a living wage.

But harder still it is to mute the Muse

Or keep their heart’s desire in a cage.

So writers, though they are of drinking age,

Will not allow surrender to the blues!

They’ll up the heat, and burst the pressure gauge!

They won’t go gentle onto that good page!

So what are your thoughts about the state of publishing-writing-print-reading these days? Any predictions for the year ahead?

![[http://www.utexas.edu/features/2010/12/06/christmas_america/ 'Santa's Portrait' byThomas Nast, published in Harper's Weekly, 1881]](https://killzoneblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Nast-Santa-300x200.jpg)