by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Some time ago I was asked on Twitter: “When you write first thing in A.M. do you work on current project or just write what comes to mind?”

Some time ago I was asked on Twitter: “When you write first thing in A.M. do you work on current project or just write what comes to mind?”

My reply: “Almost always my WIP. May do some free-form on occasion for warm up or chasing a new idea.”

The chase is what I want to talk about today. It involves five steps:

- Spark

- Nurture

- Development

- Analysis

- Green light

1. Spark

Where do ideas come from? Everywhere! A billboard, a dream, a news item, a bit of overheard conversation, a memory. Ray Bradbury would hop out of bed in the morning and write down whatever was in his head. Only later would he see if there was a whole story there.

Thus, for the creative artist, the question shouldn’t be Where can I get an idea? but Which idea should I nurture?

2. Nurture

Keep a list of the most promising sparks. Look at this list from time to time and see which ones cry out for more attention. Take these and nurture them into What if statements. I posted here about getting the spark of an idea watching the long-dead Peter Cushing make a CGI appearance in Rogue One. My spark was, Hey, maybe they’ll make movies someday with all dead actors. I nurtured that to: What if, in the future, a studio was making a Western with CGI John Wayne, and John Wayne (via AI) decided he didn’t like the script?

3. Development

Keep a file of your best What ifs. These are the ideas you’ll develop further. In the case of “John Wayne’s Revenge,” I developed it right into a short story. But most of my What ifs are ideas for full-length novels. I call this file “Front Burner Concepts.”

My preferred method of further development is what I call the “white-hot journal.” I got this from the great writing instructor Dwight V. Swain in his classic book, Techniques of the Selling Writer. Swain advocated writing a “focused, free-association document” for development. An hour to start with, at least. You’re not looking for structure, you are simply letting what Natalie Goldberg called the “wild mind” go wherever it wants to go: scene ideas, talking to yourself about why this idea is grabbing you, possible characters, settings, twists, turns, further ideas and possibilities, bits of dialogue.

Leave this document for a day, then go over it, annotate it, highlight the best parts, and add more free-form thoughts.

Do this again a third day. Start forming a cast of characters. I like to brainstorm a “relationship web,” possible connections the characters may have with each other before the story begins.

After a few days of this I have a mass of material that is starting to coalesce around a real plot. Now I’m going to ask some key questions:

- Are the stakes death (physical, professional or psychological)?

- Is there a motivated antagonist (person and/or group)?

- Are the characters starting to feel “warm” to me?

If I’m continuing to get excited, I’ll probably do some research. Since I set most of my books in Los Angeles, I’ll go “location scouting.” You always pick up great details doing live research. (See my post on this subject here.)

4. Analysis

How do you decide which project is going to take up the next three, four, six or twelve months of your writing life?

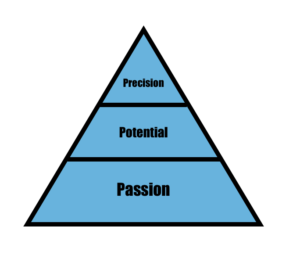

You start with Bell’s Pyramid.

Passion

The base of the pyramid is the most important. Without a passionate commitment to a story you’re burning to tell, your book will not be as original or vital or full of “voice” as it could be. You’ll risk sounding like all the cookie-cutter books competing in the marketplace. You might also get to the middle of the novel and be tempted to chuck the whole thing.

The key question here is, How emotionally invested are you in your main character? A novel, at its basic level, is about one character’s fighting a life and death battle using strength of will. That character will have to transform––becoming a fundamentally different (almost always better) person; or stronger (developing inner and outer resources in order to survive).

You should care about this character almost as much as a beloved family member. You should feel almost a need to see their story.

Potential

Now step back and consider the possible reach of your concept to an actual audience. Take off your artist’s hat and assume the role of an investor. If you were going to put up beaucoup bucks to publish your book, would it have a chance to recoup the investment and make some profit besides?

Find that sweet spot that joins your passion for the story with commercial viability.

Note, your assessment of potential need not be with the largest possible audience in mind. Genre writers know they are limiting themselves to a distinct group of potential readers. Even within genres, there are subgroups. Many science fiction writers, for example, are not writing “hard” science fiction, but rather books about deeply held philosophical ideas. They know that such novels appeal to some, and not to others. That’s fine. That’s a sweet spot, too.

Precision

Finally, be precise about your plot. You may be a plotter, you may be a pantser. In any case I advise you brainstorm the “mirror moment” for your Lead. It illuminates what your story is really all about and enables you to write organic scenes, no matter what your preferred plotting method. (Don’t worry, that moment is subject to change if the book demands it; but it’s best to have a lighthouse in a fog even if you end up in a different port.)

5. Green Light

As my wife likes to say out loud when the car in front of us has failed to notice it’s no longer a red light: “Green means go!”

And so you’re off. Write that first draft as fast as you comfortably can (refer to my post on working method here).

And that is how you chase, capture and animate an idea that you will turn into a full-length novel.

All you have to do now is add your genius.