by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Many writers are not content merely to write a good story. They want to “say something.” This is not a bad impulse. We are awash in a culture of the trivial, the trite, and the downright stupid. It is part of the writer’s calling to stand against all that.

Many writers are not content merely to write a good story. They want to “say something.” This is not a bad impulse. We are awash in a culture of the trivial, the trite, and the downright stupid. It is part of the writer’s calling to stand against all that.

I can’t recall who it was, but one novelist said, “A writer should have something on his mind.”

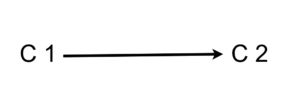

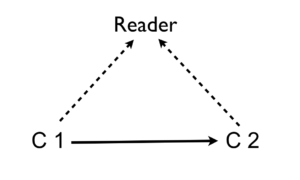

That something is the theme, or meaning, of a story. It is the moral message that comes through at the end. The noted writing teacher William Foster-Harris believed that all worthy stories can be explained as an exercise in “moral arithmetic.” In The Basic Formulas of Fiction he expressed it thus:

Value 1 vs. Value 2 = Outcome

For example, Love vs. Ambition = Love. In other words, the value of love overcomes in the struggle against ambition. If one were writing a tragedy, the outcome would be the opposite, with ambition winning out at the cost of love.

This is true even if you write without a fleeting thought about theme. Your story will have one, whether you’re conscious of it or not.

Each story has only one primary theme, which can also be stated as “Value X leads to Outcome Y.” James N. Frey says in How to Write a Damn Good Novel: “In fiction, the premise [or theme] is the conclusion of a fictive argument. You cannot prove two different premises in a nonfiction argument; the same is true for a fictive argument. Say the character ends up dead. How did it happen? He ended up dead because he tried to rob the bank. He tried to rob the bank because he needed money. He needed money because he wanted to elope. He wanted to elope because he was madly in love. Therefore, his being madly in love is what got him killed.”

So, “mad love leads to death” is the theme.

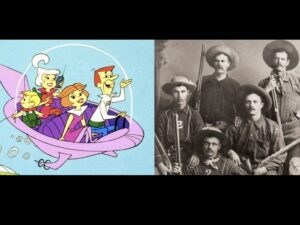

It is crucial, however, to realize that theme is played out through the characters in the story. In high school my son was tasked with a book report. He read (at my suggestion) Shane, the classic Western by Jack Schaeffer. One of the questions on his report sheet was to state the theme. He asked me for help, because he had never thought about books this deeply before.

With a little prodding, he was able to see that the homesteaders represented civilization, while the ranchers who hire gunmen represent brutality and lawlessness. Shane, of course, is the enigmatic figure who helps this moral equation become: “Civilization (a community of shared values) can overcome the forces of lawlessness.”

Look to the characters and what they are fighting for, and you will find the theme of your story.

But there is a common problem writers face when they have “something on their minds.” And that is simply that they often begin with a theme and try to force a story into it. This can result in a host of issues, among them:

- Cardboard, one-dimensional characters

- A preachy tone

- Lack of subtlety

- Story clichés

The way to avoid these is to remember: Characters in competition come before theme.

Always.

Develop your characters first—your hero, your villain, your supporting cast—and set them in a story world where their values, aims, and agendas will be in conflict. Create scenes where the struggles is vivid on the page.

Yes, you can have a theme in mind, but make it as wispy as a butterfly wing, and subject to change without notice. If you write truly about the characters, following the wants, needs, and desires, you’ll begin see the theme of your story emerge. At first it may be like the faint glow of a miner’s lamp deep in a dark cave. You may not have full illumination until the end, but it will be there.

So give your characters full, complex humanity, and then a passionate commitment to their own set of values. Even the villain. No, especially the villain. All villains (or antagonists) think they are right, and they are the drivers of the plot.

Sometimes, the theme may surprise you. That’s when writing becomes a wondrous act of self-revelation. Your story is revealing who you are and what you really care about.

Do you think about theme when you write? Or after you write? Or at any time? Have you ever been surprised at yourself when you finish a story and find a meaning you hadn’t anticipated?

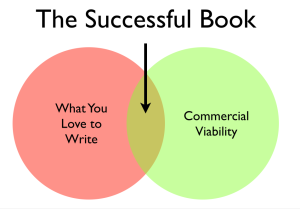

We’re over halfway through the year (ack!), so it seems an apt time to catch up on a few publishing business items. Here are five that recently caught my eye. Additions and prognostications are welcome in the comments.

We’re over halfway through the year (ack!), so it seems an apt time to catch up on a few publishing business items. Here are five that recently caught my eye. Additions and prognostications are welcome in the comments. Was she a prophet, a huckster, a healer, or a performer? Or a combination of them all?

Was she a prophet, a huckster, a healer, or a performer? Or a combination of them all?

Several weeks went by. Her stunned followers began to pray for her resurrection.

Several weeks went by. Her stunned followers began to pray for her resurrection.

We’ve had some robust discussions over the years on this matter of “rules” for writers. That word always seems to raise hackles (hackles, n., the erectile hairs along the back of a dog or other animal that rise when it is angry or alarmed).

We’ve had some robust discussions over the years on this matter of “rules” for writers. That word always seems to raise hackles (hackles, n., the erectile hairs along the back of a dog or other animal that rise when it is angry or alarmed).

Back when I was trying to learn how to write fiction, I joined the Writer’s Digest book club. Each month I’d buy a book or two, devour them, try things out. I have several shelves filled with these books, all highlighted and sticky-noted. Every now and then I like to take one down for a revisit, remembering the lessons I learned.

Back when I was trying to learn how to write fiction, I joined the Writer’s Digest book club. Each month I’d buy a book or two, devour them, try things out. I have several shelves filled with these books, all highlighted and sticky-noted. Every now and then I like to take one down for a revisit, remembering the lessons I learned.