Should black olives ever be allowed on a pizza? What about ketchup on a hot dog? What other culinary prohibitions do you follow?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Back when Lost became a TV phenomenon, I watched the first season and was just as hooked as everybody else. Man! Each episode ended with an inexplicable and shocking mystery, and I had to keep watching.

Back when Lost became a TV phenomenon, I watched the first season and was just as hooked as everybody else. Man! Each episode ended with an inexplicable and shocking mystery, and I had to keep watching.

A group of my writing friends were also caught up, posting how fabulous this all was.

But then came the second season, and I posted a warning. “It’s easy to come up with a cliffhanger if you don’t have to explain it. The day of reckoning is coming. I think you’re going to be massively disappointed.”

“Bah,” came the answers. “The show is great!”

“Just wait,” I said.

“Bah!”

Well, the day of reckoning finally came. I was on Twitter while the final episode was showing. It was a madhouse of frustration and even rage, with an occasional defense that got ratioed badly.

Some time after this, leaked documents and private conversations with the writers came out. One of the writers was asked by his friend, “How are you going to pay all this stuff off?” And the writer answered, “We’re not. We literally just think of the weirdest most f****** up thing and write it and we’re never going to pay it off.”

Mission accomplished.

But for those of us who write mysteries and thrillers we hope will sell and make fans, that’s not how we roll. We all want a satisfying, resonant ending.

I can write opening chapters all day long that’ll grab you by the lapels and get you flipping to Chapters 2, 3 and beyond. But wrapping up a twisty plot in a way that is both unpredictable and convincing? That takes some work.

That’s why, before I start writing, I have to know who the bad guy is, his motive, and his secrets. It takes imagination and brainstorming. That’s why one of the greatest plotters of the pulp era, Erle Stanley Gardner, spent hours walking around, talking to himself, working on what he called “the murderer’s ladder” before he wrote one word of a new story.

The murderer’s ladder was Gardner’s way of showing the step-by-step machinations of the villain, from the initial act of treachery (usually murder) through the first attempts at cover up, and then progressive steps to keep from getting caught.

The worth of this pre-work is that all of the villain’s steps are “off screen” in what I call the shadow story. Knowing the shadow story is the key to plotting mystery and suspense. You know what the villain is planning (the reader does not) and that spills into the present story in the form of red herrings and various ways the villain attempts to evade, frustrate, or even kill the hero.

In working out the murderer’s ladder, you avoid having to rely on a contrived ending to wrap things up.

Plus, as you outline (or just starts writing, if that’s what floats your boat), the plot starts to unfold almost automatically. I say almost because your main task now is to avoid predictability. When you know the shadow story, that’s easy. You can pause at each step and ask yourself: What is the best off screen move the villain can make? Also, ask yourself what the typical reader would expect to happen next—and then do something different. If you work off the shadow story, the ending will ultimately make sense.

Of course, your ending is subject to change without notice. Sometimes a new twist ending occurs to you as you close in on the final pages. That happened to me with Romeo’s Town. The nice thing was, the steps on the murderer’s ladder were the same. All I had to do was tweak them a bit.

Yes, endings are harder than beginnings. They’re also more important, because that’s the last impression you make on the reader. It’s what sells, in Mickey Spillane’s axiom, your next book.

The ending of this post is brought to you by The Last Fifty Pages: The Art and Craft of Unforgettable Endings.

Discuss!

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

For the last few years in L.A. we’ve been invaded by a nettlesome pest called the No-See-Um. That’s because, as the name implies, they’re hard to see. Of the family ceratopogonidae, they are tiny flying demons who bite and suck your blood.

For the last few years in L.A. we’ve been invaded by a nettlesome pest called the No-See-Um. That’s because, as the name implies, they’re hard to see. Of the family ceratopogonidae, they are tiny flying demons who bite and suck your blood.

Actually, it’s the femme fatale of species who do the biting, leaving itchy welts. The male is content to seek nectar from flowers, then lounge in a hammock with a good book. The females, on the other hand, need protein for their eggs, and seek it in our precious bodily fluid. As one site explains, “Their mouthparts are well-developed with cutting teeth on elongated mandibles in the proboscis…The thorax extends slightly over the head, and the abdomen is nine-segmented and tapered at the end.”

I mean, ick, amirite?

When summer rolls around, these creatures come out in force, like hormonal high schoolers at Zuma Beach. I don’t know if they’ve replaced the larger mosquito, but I haven’t seen the latter lately.

When the weather’s warm, I like to do morning typing outside, with a nice cup of joe at my side. But if I’m not protected in some way, like long sleeves, my skin becomes an epidermal Home Town Buffet for these airborne spawn of Hell. Indeed, I’m typing this in my backyard, and these devilish creepies are buzzing around me. It seems that when I breathe out, the CO2 attracts them, and they become ravenous for a meal.

Mrs. B has concocted a peppermint essential oil mix that we spread on our exposed skin. That frustrates the little buggers. They’re really fast, though. I try to swat them, usually to no avail. But dang it all, this is my yard, and I will not concede it to them!

You know what else? They’re small enough to get through normal screens. So when we have our windows open, a few manage to get inside our house. This has to be a bio-plot. Were they developed in some lab and unleashed upon the world? (Like that ever happens.)

Anyway, so as not to waste this unnerving experience, I extend to you a writing metaphor. There are some little pests that pop up and fly around the page, such as:

Annoying Adverbs

Elmore Leonard said, “Never use an adverb to modify the verb ‘said’ . . . he admonished gravely. To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange.”

While I’m not an absolutist on this, I think the use of adverbs should be as rare as a solar eclipse. Therefore, cut as many as possible. You can use the “end of word” Find feature in Word for this (see Terry’s explanation of that function).

Look always for a good, strong verb. Instead of He walked softly across the room use He padded across the room.

Swarming Semicolons

We’ve had this discussion before. I haven’t changed my opinion: “The semi-colon is a burp, a hiccup. It’s a drunk staggering out of the saloon at 2 a.m., grabbing your lapels on the way and asking you to listen to one more story.”

In nonfiction, the semicolon serves a good purpose. It ties thoughts together. You use them to make an argument and add evidence. But fiction is not an argument (unless your name is Ayn Rand). It’s an emotional ride, and semicolons are speed bumps. Eliminate them. Use a clean em dash or period instead.

Misplaced Attributions

I see this all the time in manuscripts by new writers. In dialogue, the attribution is often in the wrong place. The simple rule (yes, rule) is this: put the attribution after the first complete clause, or in front of the sentence. Not this:

“I don’t think we should case the joint. We should just go in with guns blasting. Then we can take the money and get out. Shock and awe, right?” said Maxwell.

This:

“I don’t think we should case the joint,” Maxwell said. “We should just go in with guns blasting. Then we can take the money and get out. Shock and awe, right?”

Or:

Maxwell said, “I don’t think we should case the joint. We should just go in with guns blasting. Then we can take the money and get out. Shock and awe, right?”

Or an action beat:

Maxwell slapped the table. “I don’t think we should case the joint. We should just go in with guns blasting. Then we can take the money and get out. Shock and awe, right?”

Elliptical Errors

And speaking of dialogue, you don’t use ellipses for interruptions. Not this:

“I don’t think…”

“Shut up, Max!”

Our friend the em dash is for interruptions:

“I don’t think—”

“Shut up, Max!”

Use ellipses for a voice trailing off.

“I don’t think…” Maxwell shook his head.

Apostrophe Befuddlement

It’s its when it’s possessive, and it’s when it’s “it is.”

Clear?

It’s not that hard! Use it’s only when you’re putting it and is together. The apostrophe is telling us there’s a letter missing. Every other time, use its. People get this wrong all the time because everywhere else the apostrophe is used to denote possession.

Which brings us to another bit of confusion. When should you use the possessive ’s for a name ending in s?

Is it: That’s James’ car or That’s James’s car?

The leading style guides recommend the latter. My personal preference is to use ’s as well, except when it sounds odd. So I use Dickens’ instead of Dickens’s.

Of course, you can avoid the whole issue by not giving your characters names ending in s.

Okay I’m tired of repeated attempts to suck my blood, so I’ll go indoors now and leave it to you to talk about any other writing pests that bother you.

Also, what’s the mosquito or no-see-um issue where you live? How do you handle it?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

The news is obviously a great place to find plot ideas. I used to clip news items from actual newspapers and toss them in an “idea box.” When getting ready to develop a new novel, I’d go through the box looking for something that still grabbed me and could be the basis of a story, or at least provide an interesting subplot.

The news is obviously a great place to find plot ideas. I used to clip news items from actual newspapers and toss them in an “idea box.” When getting ready to develop a new novel, I’d go through the box looking for something that still grabbed me and could be the basis of a story, or at least provide an interesting subplot.

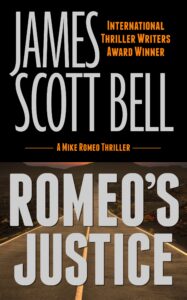

An example is my latest Mike Romeo thriller, Romeo’s Justice (which, as it happens, launches today, at the deal price of just $1.99. What a coincidence!)

For Romeo’s Justice I riffed off a story I read about the mining of lithium in California’s Salton Sea. That’s obviously timely, as electric vehicles (EVs) are being…encouraged…and lithium—lots and lots of lithium—is needed for manufacturing EV batteries. Thus, there is a rush for “white gold” and the Salton Sea is the new Sutter’s Mill. This provided both a setting and a subplot for my novel.

That’s one way to use the news—find an issue of current moment and either weave it into the narrative or make it the foundation for the main plot. Goodness knows, there are plenty of issues to choose from these days, but a word of caution is in order. A novel is not a sermon, extended rant, or thinly-disguised jeremiad. It is not 80k words worth of Twitterspeak (or should I say Xtalk?).

You’ve got to play fair with the characters. You have a strong opinion, fine, but make sure it is dramatized and not hammered. Give characters with the opposing view a justification (even if it’s just in their own minds) for what they are doing. Otherwise, a good portion of your potential readership will likely skip your other books. If they want to get yelled at they can doomscroll on X for free.

There’s another way to use headline ripping, and that’s taking an actual event and using it as the main plot. Now you’re dealing with real people, and the primary caution here is defamation.

Now, libel cases are notoriously difficult to sustain, especially in the fiction context. Though not impossible. There was the case some years ago of a novel called The Red Hat Club in which the author based a character on her (former) friend. The character in the novel is “an out-of-control alcoholic, who drinks during flights. She has sex with ‘stud puppies’ and married men, dresses provocatively, acts rude and crude, and is labeled as a ‘right wing reactionary’ and atheist with an awful temper.”

The ex-friend was not happy about this. She sued, and since she was not a “public figure” (thus bearing a more favorable burden of proof) she won.

Blue-footed booby

And so, while libel cases against novelists are as rare as the blue-footed booby, there are a few simple things you should do just to be safe.

Of course, put in the standard disclaimer: This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

But also change key facts. For example, if the real person is a man, consider making the character a woman. If he’s a lawyer, you could make him an investment banker. If the event happened in New York, set it in Los Angeles.

At the very least, change the name, for goodness’ sake. The TV show Law & Order uses real events all the time. They always run their disclaimer, then usually do an episode based on a real crime. They change things around, but one time they got lazy. In a story with the headline Was a Law & Order Episode Ripped Too Closely From the Headlines? the Hollywood Reporter documented an episode where a Brooklyn Supreme Court judge accepts cash bribes from a bald, Indian-American lawyer named Ravi Patel.

A bald, Indian-American lawyer named Ravi Batra sued the show’s creator, Dick Wolf. “In real life, Batra had close connections with a New York politician who allegedly accepted bribes and was said to have influence over a a Brooklyn Supreme Court judge.”

Defendant Wolf moved for summary judgment (a dismissal of the suit as a matter of law). But a judge denied the motion, holding that there was “a reasonable likelihood that the ordinary viewer, unacquainted with Batra personally, could understand Patel’s corruption to be the truth about Batra.”

I don’t know what ultimately happened to the case; I suspect it was settled shortly after this. But the show could easily have changed the first name of the character. Or made him a Greek-American named Xander Papadopoulos. It was careless not to.

So remember the two Ds when riffing from headlines: Disclaimer and Differences. Do that and you’re golden. (Memoir writing is another kettle of carp. See this article over on Jane Friedman’s site.)

Speaking of headlines, I can’t resist sharing a few of my favorites, gathered over the years. These are real:

Milk Drinkers Turn to Powder

Iraqi Head Seeks Arms

Something Went Wrong in Jet Crash, Experts Say

Include Your Children When Baking Cookies

Squad Helps Dog Bite Victim

Red Tape Holds Up New Bridge

Juvenile Court to Try Shooting Defendant

Complaints About NBA Referees Turning Ugly

Do you use the news for inspiration? Or just frustration?

And don’t forget:

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

One of the more ubiquitous quotes about writing out there, almost always attributed to Hemingway, is: “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

One of the more ubiquitous quotes about writing out there, almost always attributed to Hemingway, is: “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

Great quote, eh? Only problem is, Hemingway never said it, never wrote it, and probably never even thought it.

So why is he considered the source? Because some quote aggregator back in the 1970s thought it sounded like something Hemingway would say. You know, the running-with-the-bulls guy, the likes-to-box guy. He’d be all about blood.

Not.

Later, the line was given to him in a mediocre TV movie called Hemingway & Gellhorn (2012). So now you see it almost daily on X, the site formerly known as Twitter, along with another thing Hemingway never said: “Write drunk. Edit sober.” I’m starting to feel like that Britney Spears guy. “Leave Ernest Hemingway alone!!!!”

The real source for the blood quote comes down to a choice between two writers: Paul Gallico (author of The Poseidon Adventure) and the great sports columnist Red Smith. In a 1946 book, Confessions of a Story Writer, Gallico wrote:

It is only when you open your veins and bleed onto the page a little that you establish contact with your reader. If you do not believe in the characters or the story you are doing at that moment with all your mind, strength, and will, if you don’t feel joy and excitement while writing it, then you’re wasting good white paper, even if it sells, because there are other ways in which a writer can bring in the rent money besides writing bad or phony stories.

This is good advice. You can write competent fiction without feeling. Heck, that’s what AI does. But you won’t get that deep connection with the readers—and turn them into fans—unless you pour your own heart’s blood into the characters and your prose.

Shortly after Gallico’s book came out, the widely-syndicated columnist Walter Winchell quoted Red Smith as saying, “You simply sit down at the typewriter, open your veins, and bleed.” It’s likely, then, that Winchell and/or Smith paraphrased Gallico.

Smith apparently liked the blood metaphor, for in a profile in 1961 in Time magazine, he was asked how hard it was to produce a sports column every day. “Writing a column is easy,” he replied. “You just sit at your typewriter until little drops of blood appear on your forehead.”

This has a different meaning than the “bleed on the page” quote. It’s an obvious reference to the agony of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane (Luke 22:44). Smith was talking about the agony of having to come up with a fresh column idea every 24 hours (not easy!) and then write it in his singular style.

Putting these two sentiments together, I find it essential to feel something when I write a scene. Music helps. I have a playlist of various moods taken from movie soundtracks. I need an inner vibration to make a scene come alive.

And while I wouldn’t describe myself as “agonizing” (Proust-like) over my style, I do go over my words at least three times. There’s the daily editing of the previous day’s work; then the first read-through in hard copy; and a final polish. I pursue that “unobtrusive poetry” John D. MacDonald talked about. The effort, for me at least, is entirely worth it.

Mega-bestselling author John Green (Turtles All the Way Down) put it this way:

[W]riting is difficult for me. Sometimes it is difficult because I do not know what I want to say, but usually it is difficult because I know exactly what I want to say but what I want to say has not yet taken the shape of language. When I’m writing, I’m trying to translate ideas and feelings and wild abstractions into language, and that translation is complicated and challenging work. (But it is also — in moments, anyway — fun.)

It is indeed fun, and fully satisfying, to sit back and look at something you’ve written and think, “Ya know, that’s pretty darn good.” Maybe that’s what Hemingway meant when he (really) said, “For a long time now I have tried simply to write the best I can. Sometimes I have good luck and write better than I can.”

So…do you ever think of yourself as “bleeding” on the page? Should you?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Today’s post is brought to you by the new Mike Romeo thriller, Romeo’s Justice, now available for pre-order at the ridiculously low deal price of just $1.99. (Outside the U.S., go to your Kindle store and search for: B0CHMTRC6N)

Today’s post is brought to you by the new Mike Romeo thriller, Romeo’s Justice, now available for pre-order at the ridiculously low deal price of just $1.99. (Outside the U.S., go to your Kindle store and search for: B0CHMTRC6N)

Which brings me to the subject of minor characters (you’ll find out why in a moment).

First, let’s define terms. Though you’ll find variations on how fictional character types are defined, I’ll break it down this way: Main, Secondary, and Minor.

Main characters are those who are essential to the plot and usually appear in several scenes.

Secondary characters are supporting players who have a more limited, though sometimes crucial, role.

Minor characters are those who are necessary for a scene or two, and may only appear once, twice or a few times throughout.

For example, in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, the main characters are Sam Spade, Brigid O’Shaughnessy, Joel Cairo, and Casper Gutman. They recur throughout the book.

Effie Perrine, Sam Spade’s secretary, is a secondary character, who provides information and plot relief later in the story.

Wilmer Cook, Gutman’s enforcer, is a minor character, as is Tom Polhaus, Spade’s cop friend.

I call secondary and minor characters “spice.” They can add just the right touch of tasty flavor to a story. But if they’re bland or stereotypical, you’re wasting the ingredient.

So where do you start? By giving each one a tag (something physical) and a singular way of talking.

The Maltese Falcon is a masterclass in characterization. The following descriptions are for main characters, but I include them as examples of Hammett’s orchestration—making each character different in order to increase conflict.

Early on, Sam Spade gets a visit at his office from an odd little fellow named Joel Cairo.

Mr. Joel Cairo was a small-boned dark man of medium height. His hair was black and smooth and very glossy. His features were Levantine. A square-cut ruby, its sides paralleled by four baguette diamonds, gleamed against the deep green of his cravat. His black coat, cut tight to narrow shoulders, flared a little over slightly plump hips.

Cairo has a distinct way of speaking:

“May a stranger offer condolences for your partner’s unfortunate death?”

***

“Our conversations in private have not been such that I am anxious to continue them.”

Then we have the “fat man,” Casper Gutman, who—

was flabbily fat with bulbous pink cheeks and lips and chins and neck, with a great soft egg of a belly that was all his torso, and pendant cones for arms and legs. As he advanced to meet Spade all his bulbs rose and shook and fell separately with each step, in the manner of clustered soap-bubbles not yet released from the pipe through which they had been blown.

When he talks to Spade, he sounds like this:

“Now, sir, we’ll talk if you like. And I’ll tell you right out that I’m a man who likes talking to a man that likes to talk.”

***

“You’re the man for me, sir, a man cut along my own lines. No beating about the bush, but right to the point. ‘Will we talk about the black bird?’ We will. I like that, sir. I like that way of doing business. Let us talk about the black bird by all means…”

You get the idea. Physicality and speech pattern. Tags and dialogue. Even for minor characters. In Falcon, Wilmer Cook, the “gunsel,” plays a small but important role. Hammett describes him only as a “youth” wearing a “cap.” When he talks, he tries too hard to sound like a tough guy.

Dwight Frye as Wilmer Cook in the 1931 version of The Maltese Falcon

The boy raised his eyes to Spade’s mouth and spoke in the strained voice of one in physical pain: “Keep on riding me and you’re going to be picking iron out of your navel.”

Spade chuckled. “The cheaper the crook, the gaudier the patter,” he said cheerfully. “Well, let’s go.”

And while we’re on the subject of minor characters, I want to talk about how they can save your bacon when you close in on the end of your book. This happened to me as I was finishing the aforementioned Romeo’s Justice. My plot was rolling along nicely, unfurling several threads of mystery and suspense, strategically woven into the plot according to my outline. But when I got to the end, there was one thread that was still dangling. I needed to clear this up for the reader. But how?

I made up a minor character to explain it.

But wait, didn’t I just say this was at the end? You can’t just bring in some character at the very end, out of the blue, to save your keister, can you?

Of course you can! All you have to do is work that character into an early scene or two, setting him up for the big reveal.

I thumbed through my hard copy of the first draft and located a place in Act I where I could intro the character. I ended up with a minor character who I’m sure is going to show up in a future book.

This is what’s fun about being an author. You create your world and your people, and you remain sovereign over the proceedings. You can go back and move things around as you see fit. And then you can put the book up for pre-order.

What’s your approach to creating minor characters?

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

The subtitle of my book on dialogue is The Fastest Way to Improve Any Manuscript. The converse, of course, is that dialogue can sink a book pretty darn fast, too. Sodden, cliché-ridden talk is like cement shoes on a mafia stoolie. Many a book has been found at the bottom of the East River because the dialogue dragged it down.

The subtitle of my book on dialogue is The Fastest Way to Improve Any Manuscript. The converse, of course, is that dialogue can sink a book pretty darn fast, too. Sodden, cliché-ridden talk is like cement shoes on a mafia stoolie. Many a book has been found at the bottom of the East River because the dialogue dragged it down.

Before I get to the two most useless lines in literature, I have a runner-up. This couplet has been used so often it crossed over into the cliché zone around 1986:

“This isn’t about ____. It’s about ___.”

Now, you may have written such an exchange yourself, so I want to make something clear. I bear you no malice or derision. If you feel the absolute need to have a character say such a thing, I shall not throw a flag. I will, however, issue a warning. Clichés flatten the reading experience. Instead of delight, which is what you want to produce, the reader feels cheated. That feeling is usually subconscious, but why even flirt with that?

And by all means do not flirt with, entertain, or otherwise consider the two most useless lines in all literature:

“I love you.”

“I love you, too.”

I have never read this exchange (or seen it in a movie) except as a shorthand from the author demanding that I care about these people! They love each other, see? You now must love them, too, so that when tragedy befalls them you’ll really, REALLY care, because these are wonderful people who are in love, okay?

Only the effect is the opposite. It comes off as manipulation. It does nothing to make me believe the characters actually do love each other. Words are easy. You need to show me that they do. An action is aces for this, but an original line of dialogue counts as showing me, too.

Now, let’s nuance this a bit. While 98% of the time you don’t need the words “I love you,” there might be a few exceptions. Perhaps a man recovering from a traumatic brain injury, who finally opens his mouth to speak after months of silence, sees his wife at the bedside and utters, “I love you.”

Yeah, might work, though I think you could do better by thinking up some line of dialogue that was meaningful to them both early in the book, as in, “Let’s have chocolate croissants.” I dunno, you’re a writer, make something up. It’s more work than that easy-peasy “I love you,” but work that is worth it to a reader.

This cliché was demolished years ago in a commercial for a certain beer:

Or you can freshen the cliché by putting a spin on it, as Woody Allen does in Annie Hall:

ANNIE: Do you love me?

ALVY: Love is too weak a word for what—I lurve you. You know, I loave you. I luff you, with two F’s. Yes, I have to invent… of course I do. Don’t you think I do?

But for “I love you” followed by “I love you, too,” I cannot think of any exception. Find something else, anything else. The movie Ghost (1980) did it this way:

SAM: I love you, Molly. I’ve always loved you.

MOLLY: Ditto.

That word, Ditto, is not a throwaway, as it becomes a key clue later in the movie.

As I said, readers are cliché resistant. When they see one, it shoots past them without landing, without leaving any mark except a speed bump of dullness. The essence of dullness is predictability. Conversely, when you ditch a cliché for something original, it’s gladdens the reader’s heart.

UPDATE: I just remembered there’s a nuance here also. In my Romeo books, there are a couple of occasions when Mike’s friend and mentor, Ira, says something snarky yet insightful to him, and Mike replies, “I love you, too.” There it has an ironic twist. It’s also outside of the romantic love context which this post is primarily about.

So next time you’re tempted to have a character say “I love you,” and especially “I love you, too,” I want the words of Eliza Doolittle—as portrayed by the great Julie Andrews in My Fair Lady—pounding in your brain:

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I was reading in the back yard when Mrs. B came out to let me know that L.A. was in for two days of rain.

I was reading in the back yard when Mrs. B came out to let me know that L.A. was in for two days of rain.

Without missing a beat I said, “Spahn and Sain and two days of rain.”

Cindy said, “What?”

“Spahn and Sain and two days of rain.”

“What on earth are you talking about?”

I told her.

Back in my Little League days, when I was in love with baseball, the Dodgers, and Sandy Koufax in particular, I did a lot of reading in baseball history. In 1948, the Boston Braves were in a tight pennant race. They had two ace pitchers that year, Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain. In those days, ball clubs used four starting pitchers on a rotating basis. If only, fans mused, we could play the remaining games with our two stars doing all the pitching.

The sports editor of the Boston Post, Gerald V. Hern, set this hope in verse:

First, we’ll use Spahn,

Then we’ll use Sain,

Then an off day,

Followed by rain.

Back will come Spahn

Followed by Sain

And followed,

We Hope,

By two days of rain.

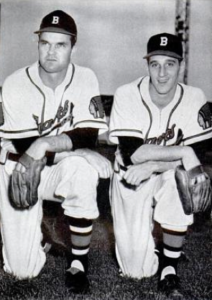

Johnny Sain and Warren Spahn

Now, who but a baseball nut from the past would know this? Bob Costas would know it. Vin Scully knew it. Yea, verily, most die-hard fans of the era would. Warren Spahn is a Hall of Famer, one of the greatest pitchers of all time. He won 363 games (winning 300 is an automatic ticket to the Hall of Fame) even though, incredibly, he missed three full seasons serving in World War II. In that capacity he won a Purple Heart and Bronze Star for action at the Battle of the Bulge.

Johnny Sain had a fine career, with 1948 as the highlight, when he was runner-up as the league’s MVP (Stan “The Man” Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals won it). He also served three years in the Navy during the war. After his retirement he became one of the best pitching coaches in the game.

So why did I want my lovely wife to know this bit of trivia? Well, because it’s part of me and my experience, my interests, my memories of love (baseball). I wanted to share it with her, have her experience the joy with me.

And that’s why I drop historical or philosophical references in my Romeo books. Those interest Mike, they’re part of him. No surprise they interest me, too, and I want to share them with my readers.

But to do so, there must be a story reason for it, and it must flow seamlessly into the narrative. Most often Mike will do this in dialogue, as with his young charge at the beach, Carter “C Dog” Weeks.

Almost always Mike explains the reference. But sometimes he’ll drop a reference and move on. It’s a risk, for the reader may be stopped short (this is not a Seinfeld reference) and wonder what it means.

And that might induce the reader to take a moment to look it up. In the “old days” to do that would be a cumbersome process of finding a dictionary or encyclopedia to seek it out. But now a couple of clicks will get you there in nothing flat.

I’m okay with that. Indeed, I get the occasional email telling me something like, “I didn’t know about ___, but looked it up. That’s pretty cool!” Indeed, Dick Francis once remarked, “If you can teach people something, you’ve won half the battle. They want to keep on reading.”

Now, I’m always mindful of doing too much of this. It can easily be overdone. In fact, editing my next Romeo, I read one of these excursions that I found entirely fascinating. But it just felt like too much. So I cut it. This was killing a darling, but we all know sometimes we must.

John D. MacDonald’s famous series character, Travis McGee, would occasionally offer personal musings about something, like what land speculators were doing in Florida or what the city of San Francisco used to be like (one wonders what ol’ Trav would think now). A few readers and critics made a minor complaint about this, but I think the larger majority—which includes yours truly—enjoyed them. They gave a deeper insight into the character.

That’s why I think it’s worth the risk.

So what risks have you taken in your writing? How’d it work out?

NOTE: I’m traveling today but will check in as I can. Cheers!

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Whenever I think of the past, it brings back so many memories. — Steven Wright

We often talk about a character’s backstory, including a “wound” that haunts as a “ghost” in the present. It’s a solid device, giving a character interesting and mysterious subtext at the beginning. The wound is revealed later as an explanation. (Think of Rick in Casablanca. “I stick my neck out for nobody” and his casual using of women. The wound of Ilsa’s “betrayal” doesn’t become clear until the midpoint).

We often talk about a character’s backstory, including a “wound” that haunts as a “ghost” in the present. It’s a solid device, giving a character interesting and mysterious subtext at the beginning. The wound is revealed later as an explanation. (Think of Rick in Casablanca. “I stick my neck out for nobody” and his casual using of women. The wound of Ilsa’s “betrayal” doesn’t become clear until the midpoint).

An often overlooked, but equally useful item, is a character’s memories. These can show up when we want a deeper look inside. It is sometimes recalled as a flashback, but can also be revealed in a dialogue exchange. One of my favorite examples of the latter is when the three friends in City Slickers are riding along together and share the best day and worst day of their lives.* In my workshops I have the students do a best day-worst day voice journal for their Lead, and suggest they do the same for other main characters, including the villain.

Another way to access this material is through your own memories. And a good way to do that is via morning pages. One exercise is to write I remember and just go. What’s the first thing that comes to mind? Follow the tangents. The other morning I did just that:

I remember a mobile hanging above my crib. Do I? Or did I formulate it later as a created memory? I don’t know, but I can see it even now.

A nursery school memory I know is real. There was a girl crying in the room, which had walls with nursery rhyme murals on them. I vividly recall a grandfather clock with a mouse running up. Anyway, I went up to the girl and started to pet her hair. I didn’t want her to be sad.

In third grade there was a girl in our class named Leslie. She was sort of an outsider. Never said much. One rainy day I was walking home from school in my raincoat when I came upon Leslie crying her little eyes out. She was having trouble holding her books, lunchbox and umbrella. So I took the books from her and offered to walk her home. Immediately she brightened up and chatted away all the way to her house.

Not long after that I was riding my bike when I made a wrong move and crashed into a tree. Down I went. My arm exploded in pain. As I lay there moaning, a woman ran out of her house to check on me. She helped me up and into her house, where she called my mom to come and get me. Mom took me to our family doctor (remember those?), the same doctor, Dr. Depper, who had delivered me into the world. My arm wasn’t broken, but it got wrapped up and put in a sling. When we got home, Mom turned on the TV. My favorite show was on, Huckleberry Hound. Mom gave me some ice cream.

About forty years later, Mrs. B and I were having dinner at a Mexican restaurant when an elderly gentleman came in with his wife and was seated.

“You see that man?” I said to Cindy. “He’s the doctor who delivered me.”

I went over. “Dr. Depper?”

“Yes?”

“I’m Rosemary Bell’s son.”

“Well I’ll be!”

“I remember your office in Canoga Park. You had a great aquarium in the waiting room.”

“Oh, yes. Those were the days, weren’t they?”

Yes indeed, those were the days, and the memories are priceless.

Do you give your characters memories?

What’s your earliest memory?

What act of kindness were you shown when you were young?

*Here’s that scene from City Slickers. It’s beautiful writing.