by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Here’s a first page for critique. The title is Savage Gunman. Genre: Western. Have a look:

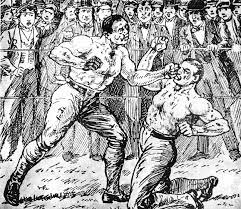

Matt Benson, a lefty, hit the massive Mexican, Juan Cortez, in the jaw with a hard right jab. Cortez’s eyelids fluttered and he took a few long steps backward on the hay-covered floor.

Matt Benson, a lefty, hit the massive Mexican, Juan Cortez, in the jaw with a hard right jab. Cortez’s eyelids fluttered and he took a few long steps backward on the hay-covered floor.

The crowd in the packed back room of the saloon roared. A drunken cowboy hollered above the rabble: “That was a lucky shot, hombre. You still got this.”

Benson crouched as soon as Cortez sprang back, charging at him. Whiffs of air swept by his ears as he imagined Cortez swinging high above his head in vain. He gripped his opponent’s tree-trunk thighs in a bear hug and used his body weight to shake the fighter until he tumbled onto his back. The thump was like an old oak thundering down from the final swing of a sharp axe.

“Get up, you bastard,” Milligan, the saloon owner shouted. “I got a fortune on you. Now ain’t the time to lose.”

Benson stood in a dizzy haze. It had been the longest fight of his life, and Cortez had worked him over pretty good for what had to have been at least a half hour at this point. His eyes couldn’t focus properly, but he took in the blurry crowd and wondered how much money in total they’d bet against him. He was half Cortez’s size and, once the men stripped shirts to fight, clearly had none of the etched muscles of the younger Mexican farmer. Years of hard work and probably even more fighting had carved those from stone.

Cortez bent his knees to arch his legs. He shifted his arms about the straw stained with blood and mud and lord knows what else. But he showed no signs of rising.

“Call it,” Benson said. “He’s knocked out. I won.”

A bald man in the crowd put spectacles on his face and hustled into the improvised ring. Down on one knee, he pinched Cortez’s cheeks and checked the eyes and face.

“His legs are up,” Milligan said. “He’s awake. Get on up now, son.”

Benson found his shirt on the ground, pulled it over his head, and started to button it.

“Not so fast,” Milligan said. “The doc hasn’t called the fight. Well, Doc?”

The bespectacled doctor stood. “He’s not out cold. He’ll be alright.”

“I’m no doctor,” Milligan continued, “but it sounds like the Mex can go another round. Hold your bets, gentleman!”

Another roar erupted.

***

JSB: There is much to like about this page. It opens with action. There’s no backstory dump to slow us down. (One bit is nicely woven in by inference: …the longest fight of his life.) The opening follows one of my axioms: Act first, explain later. It closes with the fight still in doubt, so I definitely want to turn the page to find out what happens.

Thus, my critique today is about one simple thing: cutting what Sol Stein called “flab.” Watch how a few simple cuts gives greater momentum to the scene.

Matt Benson, a lefty, hit the massive Mexican, Juan Cortez, in the jaw with a hard right jab. Cortez’s eyelids fluttered. and h He took a few long steps backward on the hay-covered floor.

The first tip here, especially for a genre like Western (or hardboiled), is that shorter sentences pack a greater punch. This goes double for a fight scene.

Now, it may be important that we find out Benson is a lefty, and I presume the author mentions it because his jab is with the right. But how essential is it to know that from the jump? Act first, explain later.

Further, that info takes us out of a close 3d Person POV (Benson wouldn’t be thinking about being a lefty. He already knows that) into Omniscient. Please note, there’s nothing “wrong” with opening in an Omniscient POV and then “dropping down” into 3d Person. It’s just that it seems more popular today to get in close and stay there.

I should also point out that a jab, hard as one may be, usually doesn’t back an opponent up a few, long steps. True, this could be a defensive maneuver by Cortez, but the way it’s presented feels like cause-effect.

The crowd in the packed back room of the saloon roared. A drunken cowboy hollered above the rabble. “That was a lucky shot, hombre. You still got this.”

I like this. The words roared, hollered, rabble are vivid. I cut the colon because I don’t like ’em in fiction. It’s not needed here where a simple period will do. A comma is also acceptable. (Just don’t get me started on semicolons!)

Benson crouched as soon as Cortez sprang back, charging at him.

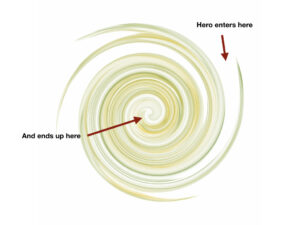

Here’s a little thing, but crucial. This violates the stimulus-response equation. (See my post on the subject here.) We have Benson crouching before we know Cortez is charging. Simple to fix. Just put the stimulus up front:

Cortez sprang back, charged at Benson.

Benson crouched.

Notice I changed charging to charged. Be very careful about violating the laws of physics by putting in simultaneous actions that don’t go together in real time. Springing back up is one action; charging ahead is another. (Yeah, I see the semicolon. Very helpful in nonfiction.) This is a common mistake and one you should train yourself to spot.

The above also offers another tip about short sentences in an action sequence: you can occasionally make separate paragraphs out of them. That conveys fast motion.

Whiffs of air swept by his ears as he imagined Cortez swinging high above his head in vain.

I’m having a little trouble picturing this. If whiffs of air are by his ears, plural, that implies at least two missed punches. I can’t see one missed punch followed by another, especially “high” above Benson’s head. And I don’t get the whiffs being by the ears unless Cortez is punching up and not over Benson’s head. Fight scenes like this can benefit by the author walking through the action physically.

I’m also not sure Benson, in the moment, would be imagining anything. Further, we don’t need to be told the punches were “in vain.”

So my advice is to rework this sentence with stimulus-response in the right spots. E.g.,

Cortez threw a right at Benson’s head. Benson ducked. A whiff of air swept the back of his neck.

Next:

He gripped his opponent’s tree-trunk thighs in a bear hug and used his body weight to shake the fighter until he tumbled onto his back.

Every style needs variety, a changeup from time to time. So a compound sentence every now and again is a good thing. The only thing I’d say here is that the he is ambiguous. It could refer to either fighter, so just change it to until Cortez tumbled onto his back.

The thump was like an old oak thundering down from the final swing of a sharp axe.

I’d like to see a little more work on this simile. I get what you’re going for. It just seems a bit cumbersome to get there (e.g., do we really need to be told the axe is sharp)? With metaphors and similes, it’s important to tweak them to get them “right.” So play around with this one. Maybe try some alternatives for the same effect. What else thumps?

“Get up, you bastard,” Milligan, the saloon owner shouted. “I got a fortune on you. Now ain’t the time to lose.”

I’m not against exclamation points in dialogue. So if this is the guy shouting, make it “Get up, you bastard!” Milligan, the saloon owner, shouted. “I got a fortune on you Now ain’t the time to lose!” [Note the grammatically required comma after owner. Also note that technically shouted is redundant in light of the exclamation point, thus said is fine. But I’m not going to call a foul.]

Benson stood in a dizzy haze. It had been the longest fight of his life, and. Cortez had worked him over pretty good for what had to have been at least a half hour. at this point. His eyes couldn’t focus. properly, but He took in the blurry crowd and wondered how much money in total they’d bet against him. He was half Cortez’s size and, once the men stripped shirts to fight, clearly had none of the etched muscles of the younger Mexican farmer. Years of hard work and probably even more fighting had carved those from stone.

I took out the last line because carved from stone is a bit of a cliché. And Benson, in the condition described, wouldn’t be wistfully pondering how Cortez got his abs.

Cortez bent his knees to arch arched his legs.

Choose one or the other. The latter is more specific.

He shifted his arms about on the straw stained with blood and mud and lord knows what else blood-and-mud soaked straw. But he showed no signs of rising.

We’re in Benson’s POV, so lord knows what is a bit much. And also the wrong tense. Plus, it takes away from the image of blood and mud, which is vivid enough.

“Call it,” Benson said. “He’s knocked out. I won.”

A bald man in the crowd put spectacles on his face and hustled into the improvised ring. Down on one knee, he pinched Cortez’s cheeks and checked the eyes and face.

“His legs are up,” Milligan said. “He’s awake. Get on up now, son.”

Benson found his shirt on the ground, pulled it over his head, and started to button it.

“Not so fast,” Milligan said. “The doc hasn’t called the fight. Well, Doc?”

The bespectacled doctor stood. “He’s not out cold. He’ll be alright.”

“I’m no doctor,” Milligan continued said, “but it sounds like the Mex can go another round. Hold your bets, gentleman gentlemen!”

This section is fine. Continued isn’t quite right, because Milligan addressed the Doc, and now the crowd. Again, no foul, but once again said does its job and gets out of the way.

Another roar erupted. The crowd roared.

A change from passive to active tense here.

So, author, I hope you take all this not as picking nits, but showing the value of small cuts at the sentence level. I hope it will help make your story a knockout.

Comments welcome.

I love this place.

I love this place.

I’ve often thought of the imagination as a muscle. With proper care and exercise, it gets stronger. Leave it alone, and it atrophies.

I’ve often thought of the imagination as a muscle. With proper care and exercise, it gets stronger. Leave it alone, and it atrophies.

Apropos of our

Apropos of our

Matt Benson, a lefty, hit the massive Mexican, Juan Cortez, in the jaw with a hard right jab. Cortez’s eyelids fluttered and he took a few long steps backward on the hay-covered floor.

Matt Benson, a lefty, hit the massive Mexican, Juan Cortez, in the jaw with a hard right jab. Cortez’s eyelids fluttered and he took a few long steps backward on the hay-covered floor. There are many ways to write a novel. That much has been made quite clear on TKZ and in the comments thereto.

There are many ways to write a novel. That much has been made quite clear on TKZ and in the comments thereto. George Horace Lorimer was the legendary editor of The Saturday Evening Post from 1899 to 1936. He brought the circulation up from a few thousand to over a million, and made it a place known for quality fiction.

George Horace Lorimer was the legendary editor of The Saturday Evening Post from 1899 to 1936. He brought the circulation up from a few thousand to over a million, and made it a place known for quality fiction.