“Don’t say ‘Hollywood’. It’ll mark you as a rank amateur or a media flake, not as a working professional. Hollywood is more like a concept, a has-been idea, than an actual production place. You’re best to say, ‘the LA-based film industry’.”

I heard those words when I ventured into film content producing. They weren’t to put me down. Rather, they were to build me up and help me break into a world I had no experience with—the film industry—and understand how important a film “treatment” is.

I think every novel writer’s dream is to see their work on the screen. At least mine was. When I wrote my first novel, I so saw it in the movies that “as the camera sees it” was my guiding light. Did it make the movies? No. Not yet.

But, my ten years of plugging along in this writing biz taught me a few things. Perseverance. Craft knowledge. Networking. And experimenting in different mediums, including screenwriting.

I’m now immersed in four film content producing projects. They keep me occupied and energized. I’m learning a lot of new stuff including how to build a “Hollywood” film treatment.

The film industry has its jargon. Logline. Tagline. Teasers. Shopping Rights. Pitch. Option. Purchase. Green Lit. Fade in. Fade out. Roll A. Roll B. Scripted. Non-scripted. Those sorts of things. But, one term I think really important for wanna-be screenwriters to understand is Treatment.

In the film industry—whether LA-based, Vancouver-based, New York-based, London-based, or Toronto-based—producers have one common problem. It’s not funding or filming. It’s finding decent (saleable) content.

Like book publishers, film producers constantly seek decent (saleable) content. They say every Barista in “Hollywood” has a screenplay for sale. Probably true, but how many are saleable?

Film producers, like book publishers, have only so much time. They’re bombarded with screenplay submissions and can’t read them all. So, the film industry has a thing similar to a book publisher’s synopsis. In the film-biz, they’re called treatments. Treatments are a structured itemization of the screenplay that stop short of going to the work of an actual script written on speculation.

Here’s a film treatment I developed for The Fatal Shot. The storyline is based on a true crime case I investigated,. It’s a similar plot to the 1984 film The Burning Bed starring Farrah Fawcett.

Here’s a film treatment I developed for The Fatal Shot. The storyline is based on a true crime case I investigated,. It’s a similar plot to the 1984 film The Burning Bed starring Farrah Fawcett.

Because of an effective treatment, The Fatal Shot is now optioned for screenplay buildout. Whether it gets green lit, who knows. At least the pitch was purchased and it’s out there, being shopped around Hollywood..

I hope you folks at the Kill Zone gain some insight into the film industry’s screenplay submission process through this treatment example. Don’t we all want to see our stories played out on the screen?

THE FATAL SHOT — FILM TREATMENT

Working Title

The Fatal Shot

Central Story Question

Who fired the fatal shot?

Logline

A battered woman charged with killing her abusive husband faces tremendous obstacles by defending herself and her children against bureaucratic criminal and social service systems. (Based on an actual incident—a true crime story.)

Tagline

“She fought her husband… now she fights the system.”

Theme

Domestic Abuse – Intimate Partner Violence – Child Protection and Apprehension – Homicide Trial – Jury Deliberations – Battered Woman Syndrome Defense

Location

Set in the American Pacific Northwest at the village of Clearwater and city of Port Townsend in Jefferson County, Washington State, on the Olympic Peninsula.

Era

Current – modern day.

Duration

18 months from inciting incident to denouement.

Protagonist

Deeana (Dee) Finnigan — 28-year-old wife and mother of boy 10 and girl 8.

Antagonists

Lyle (Finn) Finnigan — 31-year-old husband and children’s father.

Society — portrayed through dysfunctional bureaucratic structure and incompetent representatives of the criminal justice and social service systems.

Brief Storyline

Deeana Finnigan suffers 11 years of domestic terror at the fists, boots, mind, mouth, wallet, and penis of her husband, Lyle (Finn) Finnigan. Their children, Logan (age 10) and Millie (age 8), witness a deteriorating marriage and escalating violence.

Finn is on the run from a Seattle drug gang he’s double-crossed as well as arrest warrants for narcotics trafficking. He hides the family in a cramped cabin near the remote village of Clearwater on the west coast of Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula.

On a cold winter night, Finn returns to the cabin drunk. Dee’s made mac & cheese along with wieners for supper. There’s little else to eat in the place. Finn and Dee argue over the meal. Finn slaps Dee and grinds hot food into her face. He knees Dee and puts the boots to her on the floor. Logan and Millie cower in a corner, watching. Finn is enraged. He takes a rifle and threatens to shoot the family. Finn then drags Dee to the bedroom. He rapes Dee and passes out cold.

Dee’s finally had enough. She takes the rifle and shoots Finn while he’s unconscious. The first shot badly wounds Finn in the face, blowing off his lower jaw. He wakes and tries to get at her. Dee reloads to shoot Finn again. The rifle jams. Finn is incapacitated due to shock and blood loss. Dee gets Logan’s help to find another rifle and finish Finn off. Dee takes Logan and Millie to a neighbor’s house and calls the police. They’re taken to the Jefferson County seat at Port Townsend.

Investigation determines three shots were fired. One bullet got Finn in the jaw. One missed. One fatally struck Finn in the back. Dee states she fired all shots. She claims self-defense—shooting Finn to ultimately protect herself and her children from what she knows is looming, certain death. The investigators doubt Dee fired the fatal shot and believe Logan did—Dee is covering up to protect Logan. The District Attorney rejects Dee’s self defense stance. He takes the position Dee had plenty of opportunity to take the kids, leave, and have authorities intervene as the police and social systems dictate.

Dee is charged with second-degree (non-capital) murder and faces life imprisonment. She’s represented by the public defender. Dee can’t make bail. She’s half Native Indian from a Canadian reserve and considered an international flight risk. Dee remains in custody awaiting trial. Logan and Millie are apprehended by social services and made wards of the state. They’re placed in a foster home. Because the police and DA are trying to establish who fired the fatal shot to Finn’s back, a no-contact order is placed between Dee and her kids.

Dee sinks to despair. She attempts to hang herself in jail. At her lowest point, Dee undergoes a catharsis. She’s mentored by a female jail guard. They work on upgrading Dee’s education and communication skills. Slowly, Dee builds confidence. She begins to fight for what she truly wants—justice, freedom, and her children’s welfare. Dee pushes the system. And the system pushes back.

The DA hands Dee a bargain—plead guilty to manslaughter with five years in prison. The public defender wants to run a temporary insanity defense. Dee refuses both offers. She stands her ground. Dee maintains she was forced to kill Finn in ultimately protecting herself and her children, all the while denying that Logan fired the fatal shot which would have had her acquitted of murder. Years of continuous spousal battering, plus a justice and social system failing to aid her, placed Dee in a mind state where she had no option—it was kill—or eventually be killed.

The State Child Protective Services assign a spiteful social worker to oversee Dee’s children. A court application rules Logan and Millie aren’t allowed to visit Dee in jail. Dee learns the kids are being bounced between homes. Now they’re in a facility run by questionable hosts. With her jail guard’s help, Dee turns to the media.

Dee’s plight attracts intense public interest. Advocates from women’s groups surround Dee. They use the power of mainstream, internet, and social media to raise awareness of Dee’s case. Sympathizers work to crowdfund money for a competent legal defense. From jail, Dee quickly becomes a sensational face for battered women and children’s’ rights.

The criminal justice and social service systems throw continuous obstacles at Dee’s struggle to regain her children and freedom. Her private advocates are an enormous support. They find a top legal team who are passionate about the “Battered Woman Syndrome”. All work with Dee to shape that portrayal.

But as the prosecution and defense build their cases, disturbing details rise from Dee’s past. What she’s hidden, and what new evidence investigators uncover, are devastating. Rumors leak out. Stories spread. Some of Dee’s friends become foes.

After 18 months, Dee’s case goes to trial. Testimony is dramatic and unexpected. A torn jury faces forcing the law as it stands or conceding to humanity as it exists. Their decision comes down to one recurring question—not who fired the fatal shot—but why didn’t Dee just pack up the kids and leave before things became fatal? The answer lies in the Battered Woman Syndrome.

The jury struggles between wants of the system and needs of the individual. They see an enormous precedent being set with the Battered Woman Syndrome defense becoming open season on abusive men. Jurors also doubt Dee’s credibility about who fired the fatal shot into Finn. By now, most suspect Dee coerced Logan and is covering up.

Deliberations are lengthy. They hotly debate application of the law, validity of the Battered Woman Syndrome, and the parameters of self-defense. Two camps form in the jury room. Those who see the law as black and white. Those who see many shades of gray.

Overall, the jury sympathizes with Dee. They show empathy for her state of mind at the moment of the killing and her family situation. Unanimously, the jury directs an acquittal.

Dee is freed. Logan and Millie are returned. The verdict is appealed and upheld. Dee settles into a new life with her kids. She parlays her experience into helping other battered women and their children around the world.

Recurring Story Questions

Why didn’t Dee just leave? And why cover up for Logan when, at 10-years-old, he can’t be prosecuted and Dee could easily be freed?

Human Issue

The story explores Dee Finnigan’s character change from hopeless submission as a battered wife to ultimate triumph by taking defensive action against overwhelming legal and social obstacles.

Stakes

Dee’s life. Her personal freedom. Her children’s future. Worldwide precedent for the Battered Woman Syndrome legal defense. Long-term education and assistance to other victims of domestic violence.

Protagonist Character Arc

The story opens showing Deeana Finnigan displaying all the classic battered woman characteristics that come from learned helplessness. Dee is terrified of Finn but, in her mind, has nowhere to run. To survive, she’s submissive and does everything to keep from setting Finn off. Dee has poor self-esteem. She self-loathes and feels worthless. Dee’s weak mentally, physically, and spiritually. Still, she’s ultimately protective of the only thing that really matters to her in life—her children.

After experiencing the horror of Finn beating her in front of their kids, coming within a trigger’s pull of killing them, and then being sexually violated, Dee reaches an emotional plateau where she lies on the bed in desperation. She floats toward a sense of calmness and makes the decision to kill Finn.

Inwardly, Dee experiences peace. Outwardly, she’s shaking so bad that she can’t hold the rifle. Her limited control turns to chaos when Finn is wounded and claws to get at her. Terror, horror, and panic overpower Dee. Her thought process breaks, and she reacts instinctively to have Finn finished off.

Once Finn is dead, Dee is filled with relief. Her thought patterns return, and she focuses on her children’s welfare. Finn is no longer a threat, and she knows she’ll survive. Mentally, Dee makes plans for their future. She cooperates in the investigation. Dee is convinced she’s totally justified in shooting Finn. It never occurs to her the authorities would view otherwise.

Dee is incredulous when she’s arrested and charged for murder. In her eyes, killing Finn was the only recourse available to prevent her own death and her children’s demise. Her internal relief and elation at Finn being eliminated quickly ends when she’s locked up, denied bail, and loses her son and daughter to the “system”.

In total despair and at rock bottom, Dee tries hanging herself in her cell. A jail matron intervenes. This turning point lets Dee reach a catharsis or “venting the tank”. With help from the matron and advocates found through social media attention, Dee finds a progressive legal team who take on her case. The “Battered Woman Syndrome” is their card, and they play it hard.

Dee’s world view changes while she’s incarcerated, defending herself and her family as “the system” plays out. She remains steadfast in regaining custody of her son and daughter. This conflicts with her refusal to agree to a lesser charge and gain early release. Dee gambles on taking the high road for the long haul, gradually realizing that true justice will pay greater rewards than short-term compromise.

Dee also realizes greater forces are emerging, and she’s now serving a role for educating and inspiring abused women and their children. She understands the historical legal precedent she’s setting by invoking the “Battered Woman Syndrome” defense. A greater purpose drives Dee’s will to survive, be set free, create legal history, and share her story in helping other families with domestic abuse issues.

Dee experiences betrayal and disappointing setbacks when damaging information surfaces about her past. She is devastated but reacts by facing them, not denying her foes. Dee develops in inner confidence that she’ll be vindicated. Her belief in ultimate victory becomes unshakable, and her will to win is unstoppable. She finds inner peace through self-examination rather than religious redemption which is offered in spades.

Once Dee is acquitted, she shows class. She is gracious with gratitude, appreciate of all, and reflective about moving forward to help others.

The issue of who fired the fatal shot—Dee or Logan—is never resolved.

Protagonist Emotional Range/Arc

Weak – Submissive – Scared – Helpless – Self-loathing – Worthless – Protective of Children – Terrified – Enraged – Shocked – Relieved – Confused – Sickened – Trapped – Despair – Suicidal – Catharsis – Redemption – Hope – Will to Survive – Succeed – Encouraged – Inspired – Intent – Toughness – Fight – Focus – Will to Win – Betrayed – Disappointed – Nervous – Courageous – Confident – Triumphant – Gracious – Thankful – Appreciative – Reflective

Character Cast

Family and Associates:

Deeana (Dee) Finnigan — Protagonist and battered woman – jailed and tried for murder

Lyle (Finn) Finnigan — Antagonist and wife beater – shot and killed

Logan Finnigan — Son, age 10

Millie Finnigan — Daughter, age 8

Ramona Robinson — Dee’s twin sister

Andrea Sparrow — Dee’s close friend from the Canadian reserve

Valerie (Val) Bonamassa — Dee’s friend in Seattle

Muriel Finnigan — Finn’s mother – Dee’s mother-in-law

Linton Finnigan — Finn’s brother – Dee’s brother-in-law

Louise Labee, nee Finnigan — Finn’s sister – Dee’s sister-in-law

Barton (Black Bart) Smythe — Seattle Drug Gang Enforcer and DEA Informant

Police & Forensics:

Detective Alvin (Al) Kangas — Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office

Detective Stacy Rooke — Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office

Sheriff Hendrik (Hank) DeVries — Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office

Officer Patricia (Patty) Lloyd — Forensic Investigator, Washington State Patrol Crime Scene Response Team (CSRT)

Coroner Heather Tamagotchi — Jefferson County Coroner’s Office

Moses (Uzi) Galil — Seattle DEA Agent and Informant Handler

Criminal Justice System

C. Mitchell Dowd — District Attorney, Jefferson County

Jonathon Boatwright — Prosecuting Attorney, Jefferson County

Melissa Steele — Assistant Prosecutor, Jefferson County

Wallace Froude — Public Defender, Jefferson County

Emily Coulson — Lead Trial Defense Lawyer

Duncan Campbell-Elliot — Assistant Trial Defense Lawyer

Judge Morris Fish — Presiding Jury Trial Judge

Dr. Margaret Barr — Battered Woman Syndrome Expert Witness

“Margo” — Jail Guard Matron / Dee’s Mentor

Social System

Annie Lambert — Social Worker

Care Serene — Social Worker

Grace & Greer Grimsby — Foster Care Hosts

Karla Truman — Social Service Adjudicator

Media & Advocates

Ellen Capier — Port Townsend News Reporter

Rachel Vanstone — Women’s Abuse Social Media Leader & Primary Advocate

Cynne Simpson — TV Talk Show Moderator

Jennifer (Jenny) O’Donnell — Seattle TV Reporter

Gerald Gideon — Seattle Radio Reporter

Nathan Rott — NPR Investigative Reporter

Audrey Washington — CNN Investigative Reporter

Reverends John & Isobel Burke-Gaffney — Evangelists from the Reformed Baptist Church

Maria Mercedes Hernandez — Online Feminist Advocate

Nikki Daum — Native Indian Representative

Anastasia Lee — Crowdfund Organizer

Jury

12 Members Referred to as Nicknames Given by Court Staff.

“Kay” — Court Bailiff and Jury Messenger

Episode Structure

Episode One — Beating and Finn’s Death

Episode Two — Charge/Arrest

Episode Three — Children Apprehended

Episode Four — Suicide Attempt

Episode Five — Legal Adversaries

Episode Six — Black Bart

Episode Seven — Exposing Dee

Episode Eight — Trial Proceeds

Episode Nine — Retire to Deliberate

Episode Ten — Verdict and Denouement Message

Kill Zoners — Help yourself to this film treatment format. It’s not universal in the business, but it worked for me to get an option purchase.

Questions—Who out there has worked in the film industry, and who wants to? Who’s familiar with treatments, and who wants to write (or has written) a film treatment to shop their work around “Hollywood”?

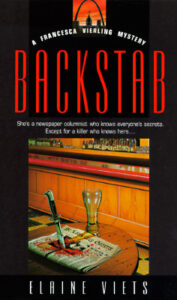

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets

But “Backstab” includes some funny stories from my time as a newspaper columnist in St. Louis. One favorite was a true story of a parking spot. St. Louis is a city where the parking spot is sacred — and never more so than on a snowy day. Those of you who have survived snowy winters know this.

But “Backstab” includes some funny stories from my time as a newspaper columnist in St. Louis. One favorite was a true story of a parking spot. St. Louis is a city where the parking spot is sacred — and never more so than on a snowy day. Those of you who have survived snowy winters know this.