“It’s the truth, even if it didn’t happen.” – Chief Bromden, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

By PJ Parrish

Liars are all the rage in publishing right now.

Whether it is that fun couple Amy and Nick Dunne in Gone Girl or that poor sot Rachel on the train, the character whose believability is compromised seems to be enjoying her day in the shadows. There seems, in fact, to be a whole sub-genre of Un-relies in YA fiction alone. (CLICK HERE).

I am just back from SleuthFest, the fabulous writers craft-con presented by the Mystery Writers of America Florida chapter, and one of my panels was on this topic. I shared the panel with my co-author sister Kelly, Debra Goldstein (Should Have Played Poker, pubbing in April) and critique group buddy Sharon Potts, whose unreliable narrator book Someone Must Die comes out this year. I have to admit, I had to do some boning up on the subject. Unreliable narrators are, for me at least, like post-modern literary fiction — I sorta kinda almost recognize it when I see it but don’t ask me to define it.

But define it we did. Or tried. The Un-Rely is a slippery fish.

Gone Girl aside, these characters have been with us for a long time now. The unreliable narrator goes back at least as far as the murderer in Poe’s The Tell Tale Heart who tries to convince us that he’s not crazy –- he’s just an excitable boy! — even though he hears his victim’s heart beating under the floorboards.

True! Nervous — very, very nervous I had been and am! But why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses — not destroyed them. Above all was the sense of hearing. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in the underworld. How, then, am I mad? Observe how healthily — how calmly I can tell you the whole story.

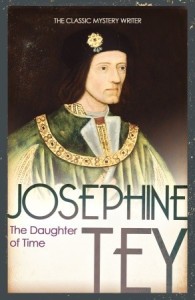

The rogues gallery of unreliable narrators is long and illustrious. Poe begat Agatha Christie’s Dr. James Sheppard (The Murder of Roger Ackroyd) who begat Kurt Vonnegut’s Billy Pilgrim (Slaughterhouse Five) who begat Ian McEwan’s Briony Tallis (Atonement) who begat Dennis Lehane’s Teddy Daniels (Shutter Island).

So are unreliable narrators all liars or nut-balls? And is this someone you want running around ranting in your head for the next year as you write your novel?

I didn’t expect a big turnout for our panel, but we packed the room. Apparently, many writers want to explore this technique, but I got the feeling most don’t really understand what it entails. So before I throw out the PROCEED WITH CAUTION signs, maybe we first need to lay down a definition.

The term “unreliable narrator” was coined by Wayne C. Booth, a literary critic and professor who in 1961 wrote a book about narrative technique called The Rhetoric of Fiction. He wrote: “I have called a narrator reliable when he speaks for or acts in accordance with the norms of the work (which is to say the implied author’s norms), unreliable when he does not.”

Well, that really clears things up, right? Try this one:

An unreliable narrator is a character whose account of the story and his commentary on it is supposed to be taken as authoritative, but for whatever reason the telling of the story and or commentary is suspect.

What are the “reasons” for the duplicity? Ah, there are many kinds of demons in the human heart and head. Here are the types of unreliable narrators I could glean from my research:

Bald-faced liars. These bad-boys take pride in playing mind games. As Holden Caulfield says, “I’m the most terrific liar you ever saw in your life. It’s awful. If I’m on my way to the store to buy a magazine, even, and somebody asks me where I’m going, I’m liable to say I’m going to the opera. It’s terrible.” Amy and Nick Dunne in Gone Girl are classic liars. One of the best liars might be Verbel Kent in the brilliant screenplay for The Usual Suspects. One of my favorite novels, Sandrine’s Case, by Thomas Cook features a really well rendered unreliable, Samuel Madison. His wife is Sandrine, who suffered from Lou Gehrig’s disease, shutting down in stages, and finally is found dead by her own hand – or was she? The novel opens with Sam’s trial for murder but is one big juicy flashback that explores his marriage and the days leading up to the trial. Cook skillfully builds suspense with Sam’s narrative, dropping “clues” that can be read in more than one way. Sam isn’t very likeable and we don’t believe him. But then the ending is turns everything on its head.

The mentally ill: In Shutter Island Teddy Daniels is a bipolar mental patient who hallucinates that he is a U.S. marshal. In the film, A Beautiful Mind, we believe John Forbes Nash is a brilliant mathematician working undercover for the government, until about halfway through we find out he is a delusional schizophrenic. In Henry James’s Turn of the Screw, it is impossible to tell if what we are reading is a ghost story or the tragic tale of a young woman undergoing a breakdown. In Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the first-person narrator is Chief Bromden, a schizophrenic. In the first chapter, he says, “God; you think this is too horrible to have really happened, this is too awful to be the truth! But, please. It’s hard for me to have a clear mind thinking on it. But it’s the truth even if it didn’t happen.”

The mentally altered or different: In Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club, the narrator has debilitating insomnia that makes his grasp of reality suspect. Amnesia figures into the veracity of narrators in SJ Watson’s thriller Before I Go to Sleep, in the cult film Memento, and in my own book She’s Not There. Post-trauma Stress Syndrome colors the reality of the Vietnam vet in the film Jacob’s Ladder and in Slaughterhouse Five, Billy Pilgrim, after the Dresden bombing, comes to believe he was abducted by a bunch of aliens. Vonnegut warns us about Billy with the book’s first line: “All this happened, more or less.”

The Naif: This narrator has limited knowledge due to a mental state or narrow world view. In Forrest Gump (Winston Groom’s novel, not the sentimentalized movie), Forrest’s 70 IQ gives him cognitive limits. We might also include here Christian, the 15-year-old autistic in Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. And even Huck Finn, who is only 14 after all tells us, “Everybody lies.”

Children: By virtue of their innocence, limited experience and gullibility, kids can’t really be trusted. In Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, the narrator is a 9 year old boy looking for his dead father after 911. In Emma Donoghue’s bestseller Room, the narrator is a 5-year-old who is trapped in a small room with his mother and talks to the furniture. He doesn’t lie, but he does say, “When I was a little kid I thought like a little kid, but now I’m five I know everything.”

Dead People: Can we really trust Susie Salmon to tell us the truth about what happened to her in The Lovely Bones? Is Nicole Kidman’s seeing dead people walking around in her manor house in The Others, or is she dead herself? And has there ever been a bigger case of denial than Dr. Malcom Crowe in The Sixth Sense?

Now here’s something to chew on: All characters we create are in a way unreliable. Unless you are using a true omniscent point of view (wherein you the writer knows all, sees all and tells all), our stories are filtered through at least one consciousness and sometimes multiple prisms. One one person can know the “truth.”

This is sometimes refers to as the Rashômon Effect. It comes from the 1950 Akira Kurosawa film Rashômon. It is a crime drama that uses multiple narrators to tell the story of the death of a samurai. Each of the witnesses describe the same basic events but differ wildly in the details, alternately claiming that the samurai died by accident, suicide, or murder. The point is that different witnesses produce contradictory accounts of the same event, though each version is equally sincerity and plausible — or suspect. I often recommend a viewing of this movie for writers struggling with multiple POVs.

So why are unreliable narrators so appealing? I think it has something to do with our readers’ expectations within the “norms” of fiction coupled with the power of the twist. think of it this way: When a character starts to tell you a story, your natural instinct is to believe him and what he is describing, feeling or thinking. If the narrator tells you the sky is blue, you believe because he gives you no reason not to. Fans of crime fiction, in particular, tend to believe the narrator because often he or she is a person of authority (cop, investigator) who acts as a sort of guide along the way to us discovering the truth.

But sometimes, the person isn’t telling you the truth or the truth is being altered through artful lying or filtered through something like a mental illness. Or we find out that our guide is actually the murderer. That’s the brilliant conceit in Agatha Christie’s seminal The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Nothing Dr. Sheppard says is technically untrue; he just hides the truth with his phrasing and omissions so we believe that he is innocent and loyal.

That’s what makes unreliables so fascinating. When the twist is revealed and we finally realize we have been lied to, the story can spin the story off into a totally new direction. But unreliable narrators are tough to pull off well. When badly handled, they can just made readers feel manipulated or confused.

So let’s talk now about some things you the writer have to keep in mind if you’re going to play this game. Here are some of take-aways from our SleuthFest panel and discussion.

Questions to Ask Yourself Before You Use Unreliable Narrators

Confess or conceal? Often, the narrator’s unreliability is made clear from the start – like Holden Caulfield telling us he’s a liar. But for more drama, some writers chose to delay the revelation until near the story’s end, thus delivering that great twist. This is common in thrillers. But here’s the problem with that – it can made readers angry. That happened with Shutter Island, I think. People either love or hate that book. Dennis Lehane is on record saying he wanted the ending to be purposely ambiguous. But a scan of Good Reads shows frustration and a lot of WTFs?

One of my favorite URs in all fiction, who tells us up front he is unreliable, is Odd Thomas in Dean Koontz’s novel of the same name. Here is the opening of Chapter One:

My name is Odd Thomas, though in this age when fame is the altar at which most people worship, I am not sure why you should care who I am or that I exist… I lead an unusual life. By this I do not mean that my life is better than yours. I’m sure that your life is filled with as much happiness, charm, wonder, and abiding fear as anyone could wish. Like me, you are human, after all, and we know what a joy and terror that is. I mean only that my life is not typical. Peculiar things happen to me that don’t happen to other people with regularity, if ever.

For example, I would never have written this memoir if I had not been commanded to do so by a four-hundred-pound man with six fingers on his left hand…When at first I proved unable to keep the tone light, Ozzie suggested that I be an unreliable narrator. “It worked for Agatha Christie in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd,” he said. In that first-person mystery novel, the nice-guy narrator turns out to be the murderer of Roger Ackroyd, a fact he conceals from the reader until the end.

Understand, I am not a murderer. I have done nothing evil that I am concealing from you. My unreliability as a narrator has to do largely with the tense of certain verbs.

Don’t worry about it. You’ll know the truth soon enough.

Can you write well in first person? All first person narrators are unreliable in their own ways because they are filtering all events through ONE CHARACTER’S biases, experiences, and beliefs. But with unreliables, that filered is complicated by extraneous influences like illness, so it’s doubly hard to pull off. Also, to pull off a satisfying unreliable narrator, you must be fully within that character’s psyche. You must know them inside and out. If you have trouble plumbing the depths of “normal” narrators, then this is not for you.

Why doesn’t it work as well in third person? Sure, there are examples of successful third-person un-relys, but I think it’s hard to writer because it can make you, the writer, seem unreliable. Readers will accept a liar telling the story. But not if that liar is you. The writer needs to be able to “hide” behind his narrator.

Can you pull off a possibly unlikeable character? Now, most of us sort of sense it when we’re being deceived, and that creates an element of mistrust. So your trick in writing an reliable narrator is to create a character who has enough empathetic characteristics that we still relate to him even though he isn’t trustworthy. You also have to create a plot that is so juicy that that readers will turn the pages even though they may not like your protagonist. I think this accounts partly for the success of Gone Girl. As gruesome as Amy and Nick Dunne were, we couldn’t look away.

Think twice about using children. Now maybe this is my personal bias showing here, but I really don’t like books narrated by little kids. Teens, yes…but anything below about 10, and I get weary. Here’s why: If you are writing an unreliable narrator, you must be in an intimate point of view. If you are in an intimate POV, your words, phrases, syntax, description – everything – must be filtered through the sensibility of a child. I gave up on The Curious Incident because I found the stream of consciousness wearing. I couldn’t get past chapter three of Room because…well, all you parents out there, tell the truth: How long can you really listen to a 6 year old? Try 352 pages then go have two stiff drinks.

Which leads me to the next question you have to ask yourself before you consider using an unreliable narrator:

Are you going for gimmick? Be honest with yourself about this. If you are writing from a child’s POV or letting a mentally unbalanced person tell your story, ask yourself: Am I doing this because of a personal feeling or am I creating a gimmick in the hopes of standing out from the crowd?

And finally…

How much stamina do you have? Being in the head of an unreliable narrator can be exhausting for you the writer. Not just because of the demands of being in an intimate POV. But because you have to constantly reassess how much – or little – information you are dribbling out to the reader. You have to be in total control of a character who often is not in control of himself. It is hard for a rational person (you the writer) to “become” an irrational person. Which is also why so many serial killer characters feel wooden.

In my case, my character Amelia Tobias, is an essentially good person. But when a head injury gives her amnesia, she loses her grasp on reality. I did a lot of research on amnesiacs and tried to understand the fragility of their reality. But to be honest, I found it easier to slip into the skin of Louis Kincaid, a biracial man, than a woman who can’t remember her past and whose grasp of her reality is constantly changing.

So did I scare you off? Does letting one of these types into your imagination sound like too much trouble? Well, it’s high risk but also high reward. When done well, like in Thomas Cook’s Sandrine’s Case or Koontz’s Odd Thomas, you get a terrific twist that also delivers a poignant pay-off. Or with a story like The Sixth Sense or The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, you’ll have readers rewinding or going back over your book muttering in amazement, “how did she do that?”

Unreliable narrators can create intrigue. They can be huge sources of tension. Readers can take great delight in discovering the reasons why behind it all. If you really want to try this, just be aware of the possible pitfalls. I got through my encounter with an unreliable and though it was a challenge, it made me stretch in new directions as a writer.

So go ahead. Give it a try. You can do this.

Would I lie to you?

Writing is a job, and working writers cannot afford writer’s block. It’s a luxury. Pros know that inspiration won’t strike like lightning. We can’t wait for it to hit us. We have to write.

Writing is a job, and working writers cannot afford writer’s block. It’s a luxury. Pros know that inspiration won’t strike like lightning. We can’t wait for it to hit us. We have to write. Early in my newspaper career, I told my editor, “I’m blocked. I can’t write this story.”

Early in my newspaper career, I told my editor, “I’m blocked. I can’t write this story.” I remember what Daniel Keyes, who wrote Flowers for Algernon, said at a speech:

I remember what Daniel Keyes, who wrote Flowers for Algernon, said at a speech: