Yearly Archives: 2014

Reader Friday: Other Things That Matter

Writers think about writing all the time. Self-publishing writers have to add all the business aspects of publishing, and everybody is on social media. It’s easy to get so focused on writing stuff that other things in life get fuzzy.

So today, take off your writing hat for a moment and talk about something else that matters to you.

Five Key Ways to Create a Character’s Distinct Voice

Jordan Dane

@JordanDane

Inspired by Joe Moore’s excellent post yesterday on Narrative Voice, I thought about my process for making characters distinct in the worlds I build in a novel. We are all influenced by where we grew up or where we live now, our race, social class, jobs, friends, religious beliefs, and other factors. Any character an author creates is no different. It’s not enough to picture their outward appearance. Give them a background and sphere of influence. Sometimes it helps for me to hear their voices in my head. (Yes, that’s allowed without taking medication. Special dispensation for authors.)

I recently binged on Sherlock (a la Benedict Cumberbatch) and Sleepy Hollow (British star Tom Mison’s reinvented Icabod Crane). I loved the notion of Sherlock’s brilliant mind leaps and I also loved the idea of a more stilted proper speech of an educated scholarly man similar to the Oxford professor of Icabod Crane, but I wanted my character to be American with a brash punch to him when he wanted to make a point. Those rare moments of punch give him a sense of gravitas and unexpected depth of personality. Being familiar with these TV characters, it became a fun challenge to meld their distinct voices and mannerisms into my American FBI profiler haunted by visions of crime scenes when he sleeps.

It’s amazing fun when you can hear the character voice in your head and write with a good pace, without filtering the words you type on the page. I call this “free association” where you channel the voice of your character without having to think about it. Over the years I’ve gotten better at this, which also comes with a cautionary warning born of experience. Often if you THINK in free association without filter, you will SPEAK that way too. Not always good in a social setting. #FilteringSavesLives

Five Key Ways to Give Your Character a Distinct Voice

1.) Word Choices:

- What is your character’s vocabulary?

- How educated is he/she?

- How much does race/culture play into his/her narrative?

- Are there regional influences on his/her speech? (I feel most comfortable writing in Midwest, TX, OK, and Alaska, places I’ve lived and worked.)

- Is slang or pop culture references a part of his/her speech patterns? (A secondary character can use slang as a way to distinguish that character’s voice from the protagonist. Fewer tag lines necessary.)

- How old is your character? (Don’t force a more youthful influence if you aren’t comfortable, but be aware of generation gaps.)

- Is your character from another country? (Word choices and even spellings can indicate where a character is from. I wouldn’t take any short cuts here. If your character is British, but YOU as the writer aren’t as familiar with nuances of a particular region in the UK, get help from a native speaker or build a backstory where your character has other influences that will temper their voice into more of a melting pot.)

- What gender is your character? (Gender can play a big part in making narrative distinctive. Avoid the cliché, but men and women are fun to contrast, no matter what your vision is for unique individuals.)

2.) Confidence Level:

- If your character is an assertive cop or from a military background, he or she would expressive themselves in a more direct and decisive fashion.

- How forceful or passive is your character? (A deliberate use of the passive voice can be an indicator of a submissive character. Use of “Uh” or “Um” can indicate hesitation and lack of self-confidence.)

- Does he or she take charge and have a no nonsense approach to dealing with conflict or do they only react and let others take over? (Even their clothes choices can indicate how confident they are.)

3.) Quirks/Mannerisms:

- Does your character have distinctive habits or mannerisms? (Sometimes a facial tic can be fun to exploit at key times.)

- Does your character have a unique hobby or interest that affects how they speak? (Someone into sailing could infuse nautical words, for example.)

- What humor do they have, if any? (Characters can have humor play out cynically in their internal monologue, yet their dialogue lines don’t reflect humor at all. This can be great for comic relief. Also characters can have distinctive sense of humor from very dry to crass bathroom humor.)

4.) Internal/External Voice:

- Your character might have a day job, but at night they come home to a family with small children or a demanding pet. How does their internal voice change when they let their guard down? Do their internal thoughts show a more tender vulnerability? This duality can bring depth and complexity to your character.

5.) Metaphors/Similes/Comparisons:

- I love imagery, but let’s face it, some characters will never think in terms of elaborate metaphors. It would not make sense to force it. In the case of my educated professor type, for example, his narrative could be infused with imagery/metaphors or perhaps literary influences because that’s how his mind works. He sees reality of the world around him yet he longs for the fictional world of his favorite book. If my character is a street kid without much education, he might be more influenced by rap music lyrics or the daily hustle on the street where he fast talks to survive everyday. No matter who your character is, they would have their own frame of reference for making comparisons.

FOR GRINS & GIGGLES: I took a little champion New York Times Online Test of 25 questions that analyzed how I spoke to determine where I live. (Best suited for residents of the U.S.) The test came back with a result that I lived in Rockford Illinois, New Orleans, and Rochester NY. Totally wrong since I live and grew up in Texas, but my mother was a Yankee and I’ve lived all over the country, so apparently that has also influenced me.) Take the test and see what your results are. Did they get it right? Let us know.

For TKZ Discussion:

How do you infuse a unique voice to your character? What are your key influences? If you’ve written characters outside your comfort zone, what tricks can you share about how to make that work?

Narrative Voice

A few weeks ago, I blogged about POV shifting and what’s called “head hopping”. To carry on with the topic of POV, I want to dig into a common topic discussed at workshops and critique group: narrative voice. Narrative voice determines how the narrator tells a story. Often it’s the voice of a character, less often, an unseen voice. The narrative voice is what provides background information, insight, or describes the actions and reactions taking place in a scene. Before a writer sets out to tell a story, she must choose which narrative voice to use. Here is a basic list and comparison of the different choices and why one might be more adventitious that the other in a particular project.

Although dialogue plays a critical role in fiction, having a story told completely with dialogue would be out of the ordinary if not downright creepy. No matter how many characters there are in a typical novel, there’s one that’s always there but is rarely thought of by the reader—the narrator. Like the referee at a football game, the narrator’s job is to impart necessary information and, in general, keep order. Someone has to tell us about mundane stuff like the time of day, the weather, the setting, physical descriptions, and the other things that the characters either don’t have time to tell us about or don’t know.

And just like the characters, the narrator—the author—has a voice or persona. Some authors like to be a part of the story and make themselves known through a distinct personality and attitude. Others prefer to remain distant and aloof, or completely transparent. One of the main things that determine the narrator’s voice is point of view.

Most stories are written in either first- or third-person. If it’s first-person, it’s usually subjective. Subjective POV tells the reader all the intimate details of the protagonist—her thoughts, emotions, and reactions to what’s going on around her. There’s also first-person objective. This story telling technique tells us about what everyone did and said, but without any personal commentary, mainly because the narrator doesn’t know the thoughts of the other characters, only their actions and reactions. First-person narration is all about “I”. I read the book. I took a walk. I fell in love.

In between first- and third-person is a rare POV called second-person. You don’t see this technique used much, and when you do, it’s about as pleasant as standing in line for hours at the DMV. Second-person narration is all about “you”. You read the book. You took a walk. You fell in love.

Next is third-person. There are a couple of third-person types starting with limited. As the term implies, this is a story technique told from a limited POV. It usually involves internal thoughts and feelings, and is the most popular narration style in commercial fiction.

We can also use third-person objective. The narrator tells the story with no emotional involvement or opinion. This is the transparent technique mentioned earlier. The interesting advantage of third-person objective is that the reader tends to inject more of his or her emotions into the story since the narrator does not.

Then there’s third-person omniscient. With this POV, the narrator pulls the camera back to see the bigger picture. He is god-like in his knowledge of everyone and everything. This POV works well when dealing with sweeping epic adventures that might span numerous generations or time periods. Unlike first-person subjective, which is up close and intimate, third-person omniscient is distant, impersonal, and sometimes cold. The reader has to use his imagination more when it comes to emotions because there’s no one to help him along. Third-person narration is all about “he, she and they”. He read the book. She took a walk. They fell in love.

The other key element in determining narration and voice is verb tense. Most stories use the past tense. This is what most readers are comfortable with. The opposite of this would be the incredibly annoying and almost unreadable second-person present tense. If you’re interested in experimental, artsy writing and want to use this technique, make sure you’re independently wealthy and have no interest in actually selling copies of your book.

So who does the talking in your books? Does your narrator’s voice seem warm and fuzzy, cleaver and funny, or cold and distant? Do you stick with the norm of third-person past tense or do you like to venture into uncharted territory? And what type of narration do you enjoy reading?

——————————-

Coming soon:THE SHIELD by Sholes & Moore

Coming soon:THE SHIELD by Sholes & Moore

“THE SHIELD rocks on all cylinders.” – James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of THE EYE OF GOD.

Forty years later, a first high school reunion

I went to my 40th high school reunion last weekend, and I’m so glad I did. I had a small and treasured group of friends in school, but over the years my peripatetic lifestyle had caused me to lose touch with them. When it dawned on me that our graduation digits were turning the Big 4-0, I decided to step on a plane and head from Los Angeles to Boston.

As anyone who has attended a major reunion for the first time already knows, it felt strange at first to suddenly reconnect with people I hadn’t seen in decades. I remembered us all as kids, but now we were all older adults. I had to quickly reconcile my memories of the past with the mature present. The gangly, shy boy I’d known is now the dapper periodontist; the former tom boy and gal pal is now the accomplished television professional.

|

| Getting my first wheels, circa ’73 |

I think we attend reunions to reconnect, not just with others, but with a sense of ourselves from an earlier time. As I sat at the reunion table, I tried to remember what I was like in high school, what my ambitions had been back then. I remember that I loved English class, especially creative writing assignments. But I didn’t connect my vague enjoyment of writing with any notion of a future career. I come from a family of scientists and academicians. Our clan regards writing as a tool, not an aspiration. I thought the ambition of becoming a writer was only meant for the literati and artistes.

I wish I’d known when I was young that “real” people can become writers. It would have helped me get started earlier. So, here’s my advice to all the high school English teachers out there: invite a local novelist to speak about writing to your class. You might just be giving that quiet girl in the third row a vision of her future.

Question for you all: have you ever braved a high school reunion before? How did it go?

Update: I just added a picture of me “back in the day”–thanks to Jordan for the suggestion!

Moving from Idea to Novel

I was presenting at my sons’ school on Friday, and one of the questions I was asked was how I turned my ideas into novels. Part of my answer was that, although I have heaps of ‘ideas’ jotted down in various journals, only about a handful of these have (so far ) developed into complete stories. This is because the majority of my ideas aren’t ‘story ready’. They’re either too flimsy or under-baked at the moment or, as I tinker with the plot options for them, turn out to be incapable of sustaining an entire story.

There are many reasons an idea fails but one question that keeps coming up is – how do you know when an idea is sufficient to carry a great story? I think the easiest way to answer this is to ask the reverse – when is it not a good idea for a story?

Like when…

- You think it’s a good idea only because it fits in with a current publishing trend

- You like the idea only because someone else told you it would make a great story

- You like the idea only because you think it will make you lots of money

Clearly, you have to love an idea to turn it into a terrific story. You have to love it because you’re going to live with it for a very long time as part of the writing process. Merely liking an idea isn’t really enough to sustain the commitment required to complete a novel.

You also have to let go of some darlings, because sometimes, no matter how much you love an idea, the characters, story and plot line simply don’t come together to make a successful story.

I adopt the following process when converting my ‘raw’ ideas into novels.

- Firstly, I jot down all my ideas. You never know which ones might stick with you or which ones, years later, suddenly resonate. That’s not to say I write down every half-baked idea I get in the middle of the night, but if I’m still mulling over it in the morning, it’s probably worth putting down in my journal.

- Then I let a few of these ideas percolate, to see which ones I am most passionate about writing about, now. Some ideas I love, but still don’t feel quite ready to explore.

- I then work through the ideas I’m most passionate about, summarising the overall premise of the story, characters, and plot overview in order to prepare a proposal (about 1-2 pages) for my agent and I to consider. Sometimes, even at this stage it’s clear I’m forcing an idea that doesn’t yet work.

- Then, once my agent and I agree on which proposal seems to stand out as the story I should work on next, I draft the first few chapters and do a more detailed plot outline to see whether it all looks as if it’s going to hang together.

Now I’ve had ideas fail at all these levels – either because the premise wasn’t clear enough, the plot was too unwieldy or, even after the first chapters and outline have been prepared, the idea still didn’t seem to work for a successful novel. (In this case, at least I discovered this before I finished the entire first draft!)

So what about you? How do you know when an idea is really ‘story ready’. How do you evaluate whether the idea is sufficient to sustain a novel? Do you plan it out or muddle through?

Will One Bad Book Ruin Your Career?

How My Daughter Became an International Multi-Media Internet Superstar Overnight

Reader Friday: The Bucket List

Cats Are the New Vampires

By Elaine Viets

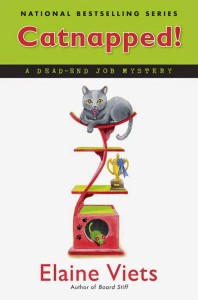

“Your next Dead-End Job mystery should be about cats,” my editor said.

I reacted as if she’d handed me a freshly used litter box.

“No,” I said. “Not cats.”

“You love cats,” she said.

I do. And I like most cat mysteries, too. But some are so cutesy they make my teeth ache. Cats are not sweet. They’re funny, they’re beautiful, they’re elegant. But I never forget that under a cat’s soft fur beats the heart of a killer.

So I persuaded my editor that I should write my 13th Dead-End Job mystery about another subject. I sent her the outline. She was underwhelmed. “You really should write about cats,” she said.

“But they’re so girlie,” I said.

“They don’t have to be,” she said. “Write the Elaine Viets take on cats.”

That’s when it dawned on me. Cats are the new vampires. They’re a subject that’s eminently portable and ever changing. Cats are whatever you want them to be: cuddly, ruthless, aloof, loveable – or all four.

Each generation reworks the vampire myth. The classic Bram Stoker vampire was the rich preying on the poor. The ’70s Frank Langella vampire was sex without responsibility – or pregnancy.

Charlaine Harris brilliantly reworked the vampire myth, and I’m not saying that just because I know her. Charlaine was already a successful New York Times mystery writer with several series when she got the idea for her Sookie Stackhouse Southern Vampire series.

Charlaine added a fresh twist. Her vampires, like gay people, lived unrecognized among us. Then the Japanese blood substitute let the vamps come out and northern Louisiana was overrun with the undead.

When other writers tell me they’re going to write a vampire mystery, I congratulate them. But I wonder if they’ll write a different vampire mystery, or simply another variation on one of the timeworn themes.

I wrote a vampire story called “Vampire Hours,” about a woman who becomes a vampire to escape the trials of middle age – an unfaithful husband, constant dieting, fading beauty. People asked me if I was going to make that story into a novel. No. My idea was different, but not universal.

But cats are universal. So I agreed to do the cat book. I’m owned by a defrocked show cat, Columbleu’s Unsolved Mysterie. She bit a judge at her first show.

I would write my new Dead-End Job mystery about the world of show cats and the people who love and care for them. I’d report on a culture.

And so Catnapped! was born. Helen Hawthorne and Phil Sagemont, my husband and wife PI team, are the in-house lawyers for a Fort Lauderdale attorney. The lawyer’s client, Trish Barrymore, is divorcing her husband, financier Smart Mort, and the only thing the couple can agree on is custody of their show cat, Justine.

When Mort fails to return the cat on time, Helen and Phil are sent to collect the cat. They find Mort dead and Justine kidnapped and held for half a million dollars. Helen goes undercover to work for a show cat breeder.

Judge Tracy Petty, Cat Fanciers’ Association southern region director, helped with the cat show details.

Did you know that long-haired show cats have to be bathed – and they learn to like it? Their fur is so thick they are slathered in Goop, the mechanic’s hand cleaner, and then the cats get two shampoos, a conditioner and more. Their fur is dried with a special blow dryer. There’s more. Much more. But you’ll have to read the book to find it out.

When you pick your next subject, ask yourself: How novel is it? How universal?

Catnapped! is two days old today. Too young to know if I have a were-tiger by the tail, like Charlaine. But my show cat is scratching her way up the charts.

___________________________________

Check out the first chapter and the book trailer for Catnapped! at www.elaineviets.com