By Mark Alpert

Choosing a title for your novel should be fun, right? So why is it often so frustrating?

I think it’s because there are so many requirements for a good title. It has to tell the reader, in a general way, what the book is about. It also has to convey the tone of the book — a light, amusing title for a lighthearted novel, a heavy, ominous title for a dark, creepy thriller. It can’t be too similar to titles of other recently published or very well-known books. And it shouldn’t carry the baggage of unwanted associations. Above all, it has to be catchy.

One could argue that novelists shouldn’t worry so much about titles. This is an area where the publisher has the final say, because the title is so important to the marketing of the book. The author can make suggestions, but the publisher has veto power. And I’ve learned that the best titles often come out of brainstorming sessions between the author and editor after the book is finished. But I can’t start a novel without giving it at least a working title. I can’t just call it a work-in-progress. Would you call one of your kids a work-in-progress? (Although that’s what children are, really.)

I’ve written four published novels, and each had a working title that was different from its ultimate title. When I started writing the first book I called it “The Theory of Everything” because it was about a dangerous secret theory developed by Albert Einstein to explain all the forces of Nature. (Einstein himself called it Einheitliche Feldtheorie, the unified field theory.) But that wasn’t such a great title for a thriller. It seemed better suited to a literary novel. (And, in fact, there are several literary novels titled “The Theory of Everything.”) So my editor and I put our heads together and came up with “Final Theory.” That seemed more compelling and yet still true to the subject of the book, because physicists believe that if they ever do discover a theory of everything, it will also be a final theory (because they will have nothing fundamental left to discover).

My second novel was a sequel to the first, and I gave it the working title “Quantum Crash” because it was about an attempt to crash the program of the universe. Because the universe is inherently mathematical, some physicists have speculated that reality is the result of a cosmic program; the laws of physics are the operating instructions of this program, while matter and energy are the data being crunched. The problem with this title was the word “quantum.” I think the publisher was worried it would scare off some readers. My editor proposed the title “The Omega Theory,” which had the advantage of conveying that the book was a sequel to the first novel. Luckily, there is a concept in physics called the omega point, and I was able to work this into the book’s plot.

My third book was a stand-alone novel about the merger of man and machine. The working title was “Swarm” because the book’s villain employs swarms of cyborg insect drones — live houseflies with implanted radio controls and bio-weapons — to attack the heroes. But that title didn’t convey the general premise of the novel, which describes the rise of a man-machine network that seeks to exterminate the human race. So my editor and I came up with “Extinction,” which was much better.

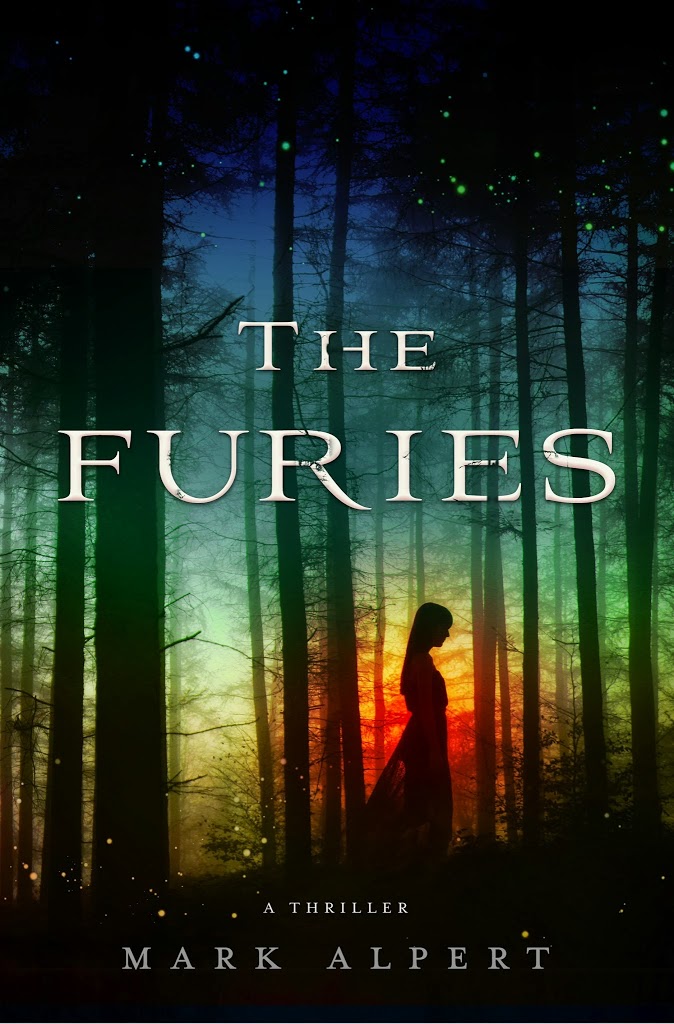

My fourth novel (which just came out) is another stand-alone, this one about an ancient clan of witches who have steered the course of human history for centuries. I gave it the working title “Ariel” because that was the name of the heroine, but I knew it would never fly as the ultimate title because of all the “Little Mermaid” associations. In the end my editor and I settled on the title “The Furies,” which are Greek mythological witches of a sort. I changed the name of the witch clan to Fury so that the book’s title would better fit its content.

And right now I’m writing a novel about an alien invasion, and I’ve given it the working title “Interstellar.” But I’m pretty sure this won’t be the title when the book is published because there’s a movie called “Interstellar” that’s scheduled to come out by the end of the year. I just viewed the trailer for the movie and it looks pretty cool. But my novel, whatever it’s ultimately called, will be very different.