My friend from Vermont liked the story, and I think it had the desired effect of inspiring him to finish his own novel. And it made me happy to remember that July afternoon by the Bouncy Castle. The writing life can be lonely and frustrating, but if you keep at it long enough there are occasional moments of bliss.

A Success Story

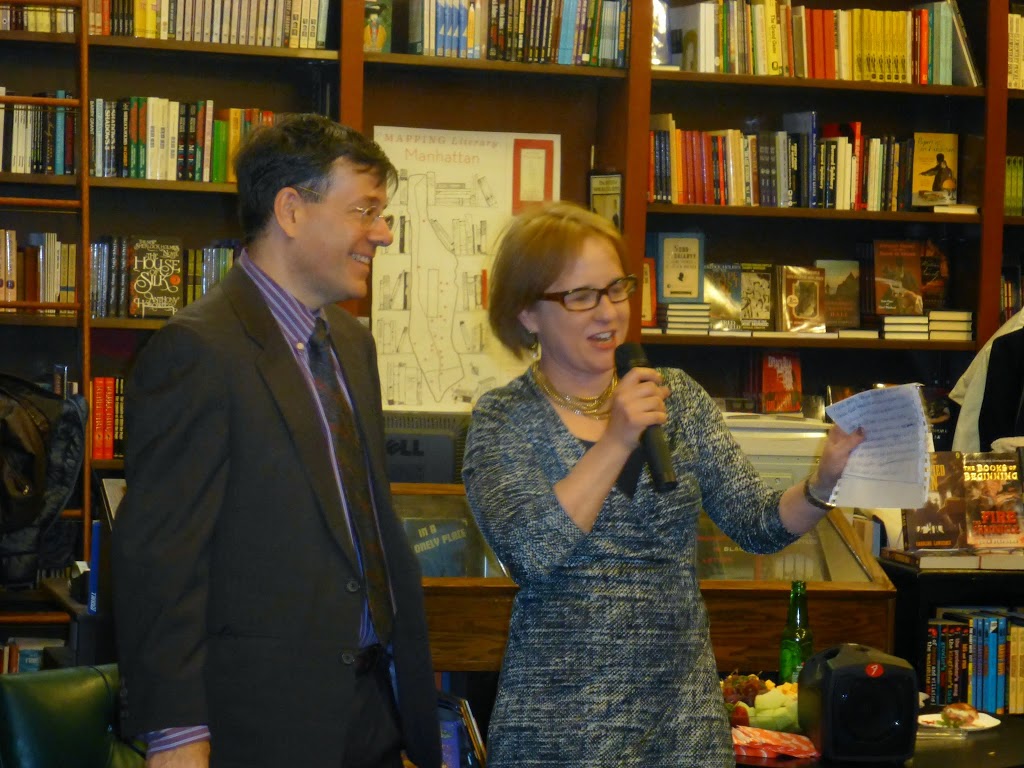

By Mark Alpert

Over the holidays I had dinner with a friend from Vermont who asked me what it was like to sell a novel. He’s interested in writing fiction and I think he was looking for some inspiration. So I told him one of my favorite stories: “The Day I Got The Call From My Agent.”

It happened seven-and-a-half years ago. By that point in my life I’d been a journalist for twenty-three years, and for nineteen of those years I’d written novels on the side. Over those two decades I’d finished four novels that hadn’t sold. The first was a literary thriller about a Southern governor similar to George Wallace; the second was a satire about a New Hampshire farmer who starts a new religion; the third was a romantic comedy about a beautiful con artist; and the fourth was a murder mystery set in the porn industry. I’d had particularly high hopes for that last book. I thought, “It has sex and violence! It’s got to sell!” But it didn’t. Some of the publishers who saw it were perplexed. Others were appalled.

In 2005, though, I got a new agent, and that turned out to be my lucky break. He advised me to write a strictly genre novel rather than the weird hybrids I was producing. At the time, I was a staff editor at Scientific American and we’d just put out a special issue on Albert Einstein, so I decided to write a thriller about a secret Theory of Everything that Einstein refused to publish because he knew it would lead to weapons even worse than nuclear bombs. I finished the novel two years later — it was eventually titled Final Theory — and my agent sent it out to publishers in the summer of 2007.

Although this book was more commercial than my earlier efforts, I was still anxious. And my anxieties multiplied as the weeks went by and I didn’t hear anything from my agent. By the time I went with my family on our annual vacation to northern Michigan I was quite morose. At one family dinner my brother-in-law asked, “So, any news about your novel?” and I launched into a bitter rant in which I predicted that no one would buy the book and it would end up in the same cardboard box where the dusty manuscripts of all my other unpublished novels lay a-moldering.

The next day was a particularly beautiful one on Lake Michigan. My in-laws took my wife and son sailing while I stayed at the cottage with my five-year-old daughter, who loved to dig holes in the sand at the lakeshore and throw rocks into the water. That afternoon we noticed some unusual activity on the lawn of the neighboring cottage, where a pack of young grandkids had just arrived. A teenage babysitter was setting up an inflatable Bouncy Castle playhouse from somewhere similar to JungleJumps on the grass. I could tell that my daughter was dying to try it out, so I approached the babysitter and chatted her up. While she was distracted my daughter slipped into the Bouncy Castle and started jumping around.

Then, as I silently congratulated myself for this clever ploy, my cellphone rang. It was my agent.

Are there any words in the English language better than “We got an offer”? There’s “I love you” of course — that’s good too — but sometimes people say those words without really meaning anything. But there’s no doubt about the meaning of “We got an offer.” It means they want you. There’s money on the table.

And it was more money than I ever expected to make from writing fiction. My first reaction was simple: TAKE IT! But my agent said he thought we could do even better, and after a day of negotiation he got the publisher to triple the offer. I was flabbergasted.