It was a dark and stormy night.

If you were the first writer to have used that as an opening line, then it was brilliant. What a vivid way to create an immediate setting and mood. Congratulations on a fresh, original beginning. For everyone else, that line is a cliché. A language cliché to be exact. In addition to language clichés, there are character and plotting clichés. We all know not to use them, but sometimes they slip through when we’re not looking. So how do we avoid clichés like the plague and fix them in the blink of an eye?

First, let’s define the three types. As mentioned, language clichés are bits of speech that have been used so often they lose their original luster or charm. You’d have to be blind as a bat to not understand my crystal clear definition. It should hit you like a ton of bricks.

Character clichés are those we’ve seen too many times such as the prostitute with a heart of gold (includes a language cliché) or the disgraced, wrongly accused cop who winds up catching the killer.

Plotting clichés are well-worn storylines such as the farmer boy who turns out to be a king or the self-taught musician who eventually performs with the philharmonic. Two common plotting cliché examples that I’ve seen dozens of times are books and movies based on the “Bad News Bears” and “Death Wish” themes. The Bad News Bears theme usually deals with a group of outcasts or “losers” who reach the lowest point in their collective lives only to be pulled together by a strong, charismatic leader and wind up coming out winners. This theme does not have to deal with sports. Watch the movie THE HOUSE BUNNY as a good example.

The Death Wish theme is usually the story of a common “every man” who experiences a tragic event in his or her life. Seeking justice but not getting help from the police or government (or any authority group), he/she steps out of a normal existence, takes matters into his/her own hands and finds justice and revenge by becoming judge, jury and executioner. THE BRAVE ONE is a great example of the Death Wish theme. It’s only through unique characters or settings that these clichéd themes keep working. Try to avoid them at all costs.

Language clichés are fairly easy to spot and fix like the one in the previous sentence. They often appear in your first or second draft when you’re writing fast in order to get the story onto the page, and you don’t want to stop your momentum to think of an original description of a character or setting. There’s nothing wrong with that because you have every intention of going back and cleaning them up.

My first tip is to do your cliché hunting with a printed copy of your work, not on the computer screen. As you read along, use a color highlighter and mark everything that’s a cliché or even questionable. Then go back to the computer and take the time to consider each one and how you can improve them. In some cases, just substituting the real meaning in place of the cliché is enough. For instance, he’s as crazy as a loon could become he’s insane. Isn’t that what you really meant? How about, that kind of book is not my cup of tea could become I don’t enjoy that kind of book. Again, that’s the meaning you intended, so simply stating it could fix the problem better than relying on a cliché. Taken out of context, these might sound boring, but chances are that simplifying the meaning won’t stop the reader like a worn out phrase might. One caution though: it’s important to maintain and be true to your “voice” when using this simplifying technique.

One place where you can sometimes get away with clichés is in dialog. But that doesn’t mean you should. If a character uses a cliché, make sure it’s part of his or her “character” and not just an excuse for lazy writing.

Character clichés are a little harder to fix, but the sooner you do, the better off you’ll be, and the more original your story becomes. Here’s an example: the disgraced cop is an anti-hero. He’s got deep dark issues but we still pull for him because he’s fighting for what’s right. Maybe he’s an alcoholic because he can’t get over the murder of his family. Try removing one of the main elements that drive the character; the disgraced career, the alcohol addiction or the dead family. Does his character change in your mind? Does he become more interesting? Can you still tell his story? If taking away or substituting an element suddenly creates a fresher character, you’ve probably avoided a character cliché. Another tip: If your character’s action shows a serious lack of common sense, treat it as a cliché. You should always be considering what you would do in the same situation as your character. Would you react the same as what you just made your character do? If not, it’s probably a cliché.

Plot clichés need to be fixed from the start. The further you are into the story, the more work it takes to backtrack and change major elements. So before you begin, try this. Write out a short description of your story. Approach it as if you were writing the story blurb to go on the back cover of your book. Once you’re done, ask yourself if sounds familiar. Let someone else read it and ask the same question. If you can remember the same situation occurring in numerous movies, TV shows or books, it’s probably a cliché.

There’s nothing wrong with a cliché as long as you’re the first person to use it. After that, it loses its luster fast. Not only that, it’s a sign of lazy writing. As a good friend of mine once said, a cliché is the sign of a mind at rest.

How do you perform a “seek and destroy” on clichés? And how do you feel when you come across one in a book. If the story is really great, do you overlook clichés or do they cause you to think less of the writer?

——————————-

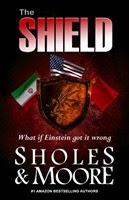

Download now: THE SHIELD by Sholes & Moore

Download now: THE SHIELD by Sholes & Moore

“THE SHIELD rocks on all cylinders.” – James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of THE EYE OF GOD.

Coming soon in print and audio.