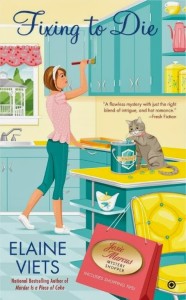

by Jodie Renner, editor & author

by Jodie Renner, editor & author

Follow Jodie on Twitter

Imagine you’ve just met someone for the first time, and after saying hello, they corral you and go into a long monologue about their childhood, upbringing, education, careers, relationships, plans, etc. You keep nodding as you glance around furtively, trying to figure out how to extricate yourself from this self-centered boor. You don’t even know this person, so why would you care about all these details at this point?

Or have you ever had a friend go into great long detail about someone you don’t know, an acquaintance they recently ran into? Unless it’s a really fascinating story with a point, I zone out. Who cares? Give me a good reason to care, and feed me any relevant details in interesting tidbits, please!

In my editing of novels, I’ll often see a new character come on scene, then the author feels they need to stop the action to introduce that person to the readers. So they write paragraphs or even pages of background on the character, in one long expository lump. New writers often don’t realize they’ve just brought the story to a skidding halt to explain things the readers don’t necessarily need to know, certainly not to that detail, at that point. And it’s telling, not showing, which doesn’t engage readers. In fact, they’ll probably skim through it, and more likely, find something else to do instead.

Another related technique I find less than compelling is starting with the character on the way to something eventful, and as they’re traveling, they’re recollecting past or recent events in lengthy detail. It’s much more engaging to start with the protagonist interacting with others, with some tension and attitude involved. Then work in any necessary backstory info bit by bit as the story progresses, through dialogue, brief recollections or references, hints and innuendo, or short flashbacks in real time. And through reactions and observations by other characters.

Rein in Those Backstory Dumps!

Contrary to what a lot of aspiring authors seem to think, readers really don’t need a lot of detailed info right away on characters, even your protagonist. Instead, it’s best to introduce the character little by little, in a natural, organic way, as you would meet new people in real life. You might form an immediate physical impression, especially if you find them attractive or repugnant. You notice whether they’re tall or short, well-groomed or scruffy, timid or overbearing, friendly or cold, intelligent or dull, charismatic or shy.

If you’re interested in them, if you find them intriguing, you pay attention to them, ask them questions, and maybe ask others about them. You gather info on them gradually, forming and revising impressions as you go along, with lots of unanswered questions. Maybe you hear gossip, and wonder how much of it is actually true. Through conversation and observation, you formulate impressions of them based on what they (or others) say, as well as their attitude, personality, gestures, expressions, body language, tone of voice, and actions.

Involve and engage the readers.

It’s also important to remember that readers like to be involved as active participants, not as passive receptors of dumps of information. Finding out about someone bit by bit, trying to figure out who they are and what makes them tick, what secrets they’re hiding, is a stimulating, fun challenge and adds to the intrigue.

Unlike nonfiction, where readers read for information, in fiction, readers want to be immersed in your story world, almost as if they’re a character there themselves. So be sure to entice readers to get actively engaged in trying to figure out the characters, their motivations and relationships, and whether they’re to be trusted or not.

Let the readers get to know your characters gradually, just like they would in real-life.

For ideas on how to approach introducing your characters to the reader in your fiction, think about a gathering where you’re just observing for a while, trying to get your bearings, maybe waiting for some friends to arrive. You look around at who’s there, listening in to snippets of conversation. A few people interest you so you move closer to them, trying not to be obvious. You might pick up on glances, smiles, frowns, rolling of eyes, and other facial expressions. You read their body language and that of others interacting with them.

Perhaps you decide to strike up a conversation with one or two who look interesting. You find out about their personality and attitudes through their words, tone of voice, inflection, facial expressions, body language, and the topics they jump on and others they avoid. Then, if they interest you, you might start asking them or others about their job or personal situation and get filled in on a few details – colored of course by the attitudes and biases of the speaker. Maybe you hear a bit of gossip here and there.

That’s the best way to introduce your characters in your fiction, too. Not as the author intruding to present us with a pile of character history (backstory) in a lump, but as the characters interacting with each other, with questions and answers, allusions to past issues and secrets. Even having your character thinking about what they’ve been through, isn’t that compelling, so keep it to small chunks at a time, and be sure to have some emotions involved with the reminiscing – regret, worry, guilt, etc.

So rather than stopping to give us the low-down on each character as he comes on the scene, just start with him interacting, and let tidbits of info about him come out little by little, like in real life. Let the readers be active participants, drawing their own conclusions, based on how the characters are acting and interacting.

Reveal juicy details, little by little, to tantalize readers.

And don’t forget, the most interesting characters have secrets, and readers love juicy gossip and intrigue! Just drop little hints here and there – don’t spill too much at any one time. Give us an intriguing character in action, then reveal him little by little, layer by layer, just like in real life!

Readers and authors, do you have any observations or advice to offer on dealing with character backstory in fiction?

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources to date: Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage. You can find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, her blog, http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/, and on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.