By Sue Coletta

First, let’s define the word “muse.”

First, let’s define the word “muse.”

A muse is a woman, or a force personified as a woman, who is the source of inspiration for a creative artist. How amazing that we’re able to tap into her energy and translate our story to the page.

An alternate definition of “muse” is an ancient Greek word that means to be absorbed in thought or inspired. Amusement is the absence of thought or inspiration. Hence why social media can destroy our creative time. Over saturating ourselves with anything, including thoughts, outside and inner pressure, too many ideas, etc., can wound our muse. Ever notice that some of our best ideas come when we’re falling asleep or taking a shower or walk? That’s because our mind is relaxed. For those that struggle to structure themselves should consider using a matching worksheet maker to help them keep on track with educational tasks, they have laid out for themselves to improve their creativity.

What happens inside the brain?

Dr. Lotze from the University of Greifswald had always been fascinated by the creativity of writers, so he wondered how the brain reacted when they crafted stories. In a scientific study, he took novice writers who’d never completed a story and professional writers who’d authored published books. The results amazed him.

Did you know our brains react differently, depending on whether an author writes professionally or if they’re just beginning their writing journey?

First, Dr. Lotze built a custom-made writing desk. While lying supine, their head cocooned inside the scanner, the subject rested their arm on a wedged block. He positioned several mirrors which allowed the writers to see what they were writing.

Novice Writers

Dr. Lotze asked 28 volunteers to first only copy a block of text. This gave him a baseline of brain activity. Next, he gave them the first few lines of a short story and told them to continue on. Thus, triggering their muse. They were allowed to brainstorm for one minute, write for two.

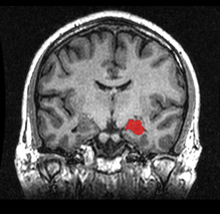

Hippocampus in red.

The research showed certain parts of the brain became active during the creative process but not while copying text. During brainstorming, some vision-processing regions also came alive in some of the writers, as if they were seeing the scene unfold in their mind’s eye.

During the writing process, other regions activated, as well. Dr. Lotze theorized that the hippocampus was retrieving factual information for the subjects to use in their stories. Who says research isn’t important?

Another region of the brain, near the front — left caudate nucleus and left dorsolateral and superior medial prefrontal cortex, which is crucial for storing several pieces of information at once — also activated. When writers juggle characters and plot lines we put special demands on that part of the brain.

The problem with this study was that he’d chosen all novice writers.

What happens inside the mind of a seasoned writer?

Twenty authors volunteered this time. In the same position as the novice writers, Dr. Lotze gave seasoned writers the exact same instructions. Brainstorm for one minute, write for two. Like before, the first few lines had been written for them.

Dr. Lotze’s findings are as follows …

During creative writing, cerebral activation occurred in a predominantly left-hemispheric fronto-parieto-temporal network. When compared to inexperienced writers, researched proved increased left caudate nucleus and left dorsolateral and superior medial prefrontal cortex activation. In contrast, less experienced participants recruited increasingly bilateral visual areas. During creative writing, activation in the right cuneus showed positive association with the creativity index in expert writers.

High experience in creative writing seems to be associated with a network of prefrontal and basal ganglia (caudate) activation. In addition, the findings suggested that high verbal creativity specific to literary writing increased activation in the right cuneus associated with increased resources obtained for reading.

You can read the full report here.

Let’s break it down in easier terms.

The brains of seasoned writers worked differently than novice writers, even before they began to write. During the brainstorming, the novice writers showed more activity in the brain’s regions responsible for speech.

“I think both groups are using different strategies,” said Lotze. “It’s possible that the novice writers are watching their stories like a film inside their head while the professional authors are narrating it with an inner voice.”

He discovered more differences.

Deep inside the brain of seasoned writers, a region called the caudate nucleus, responsible for skills that require a lot of training and practice, also became active. In the novice writer, it didn’t. The caudate remained quiet. Perhaps that’s due to the fact that when we start learning a skill we’re more consciously trying to master it. With practice, those actions become largely automatic, and it’s inside the caudate nucleus where the shift occurs.

Skeptics like Dr. Pinker, another scientist, said the test wasn’t involved enough to make comparisons. He’d rather see tests between writing fiction vs. nonfiction or other factual information. Creativity might also cause differences from writer to writer. For example, some writers may activate the taste-perceiving regions in the brain when they write about food. Another writer might rely more on sound. Paul Dale Anderson wrote a fascinating post that touched on this difference in more depth.

What’s the best way to summon creativity?

Read a book, listen to music or audiobooks — any exercise that forces us to envision someone else’s story world. A passionate and focused writer can accomplish more in a few hours than an unfocused writer can in a full day.

Over to you TKZers. What do you think of this study? Are you an auditory or visual writer? While writing, can you taste the food?

By the time we travelled to Bath I was ready for the next few gems, including a reference to a potential character in the Bath abbey and a visit to a charming town in the Cotswolds that had a small medieval church and graveyard that could totally be used in a future book.

By the time we travelled to Bath I was ready for the next few gems, including a reference to a potential character in the Bath abbey and a visit to a charming town in the Cotswolds that had a small medieval church and graveyard that could totally be used in a future book.