With all that holiday frivolity behind us, I’m going to continue my quest to help writers understand some of the technical aspects of weaponry so that their action scenes can be more realistic. Today, we’re going to talk about some practical applications for high explosives. It’s been a while since we last got into the weeds of things that go boom, so if you want a quick refresher, feel free to click here. We’ll wait for you.

Welcome back.

When I was a kid, the whole point of playing with cherry bombs and lady fingers and M80s was to make a big bang. Or, maybe to launch a galvanized bucket into the air. (By the way, if you’re ever tempted to light a cherry bomb and flush it down the toilet, be sure you’re at a friend’s house, not your own. Just sayin’. And you’re welcome.) As I got older and more sophisticated in my knowledge of such things, I realized that while making craters for craters’ sake was deeply satisfying, the real-life application of explosives is more nuanced.

Since TKZ is about writing thrillers and suspense fiction, I’m going to limit what follows to explosives used as weapons–to kill people and break things. Of course, there are many more constructive uses for highly energetic materials, and while the principles are universal, the applications are very different.

Hand grenades are simple, lethal and un-artful bits of destructive weaponry. Containing only 6-7 ounces of explosive (usually Composition B, or “Comp B”), they are designed to wreak havoc in relatively small spaces. The M67 grenade that is commonly used by US forces has a fatality radius of 5 meters and an injury

only 6-7 ounces of explosive (usually Composition B, or “Comp B”), they are designed to wreak havoc in relatively small spaces. The M67 grenade that is commonly used by US forces has a fatality radius of 5 meters and an injury  radius of 15 meters. Within those ranges, the primary mechanisms of injury are pressure and fragmentation.

radius of 15 meters. Within those ranges, the primary mechanisms of injury are pressure and fragmentation.

For the most part, all hand grenades work on the same principles. By pulling the safety pin and releasing the striker lever (the “spoon”), the operator releases a striker–think of it as a firing pin–that strikes a percussion cap which ignites a pyrotechnic fuse that will burn for four or five seconds before it initiates the detonator and the grenade goes bang. It’s important to note that once that spoon flies, there’s no going back.

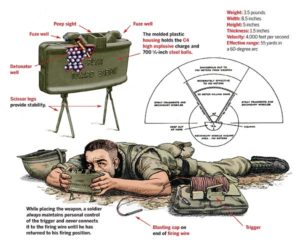

Claymore mines operate on the same tactical principle as a shotgun, in the sense that  it is designed to send a massive jet of pellets downrange, to devastating effect. Invented by a guy named Norman MacLeod, the mine is named after a Scottish sword used in Medieval times. Unlike the hand grenade, which sends its fragments out in all directions, the Claymore is directional by design. (I’ve always been amused by the embossed letters on the front of every Claymore mine, which read, “front toward enemy.” As Peter Venkman famously said while hunting ghosts, “Important safety tip. Thanks,Egon.”)

it is designed to send a massive jet of pellets downrange, to devastating effect. Invented by a guy named Norman MacLeod, the mine is named after a Scottish sword used in Medieval times. Unlike the hand grenade, which sends its fragments out in all directions, the Claymore is directional by design. (I’ve always been amused by the embossed letters on the front of every Claymore mine, which read, “front toward enemy.” As Peter Venkman famously said while hunting ghosts, “Important safety tip. Thanks,Egon.”)

The guts of a Claymore consist of a 1.5-pound slab of C-4 explosive and about 700 3.2 millimeter steel  balls. When the mine is detonated by remote control, those steel balls launch downrange at over 3,900 feet per second in a 60-degree pattern that is six and a half feet tall and 55 yards wide at a spot that is 50 meters down range.

balls. When the mine is detonated by remote control, those steel balls launch downrange at over 3,900 feet per second in a 60-degree pattern that is six and a half feet tall and 55 yards wide at a spot that is 50 meters down range.

The fatality range of a Claymore mine is 50 meters, and the injury range is 100 meters. (Note that because of the directional nature of the Claymore, we’re noting ranges, whereas with the omnidirectional hand grenade, we noted radii.)

Both the hand grenade and the Claymore mine are considered to be anti-personnel weapons. While they’ll certainly leave an ugly dent in a car and would punch through the walls of standard construction, they would do little more than scratch the paint on an armored vehicle like a tank. To kill a tank, we need to pierce that heavy armor, and to do that, we put the laws of physics to work for us.

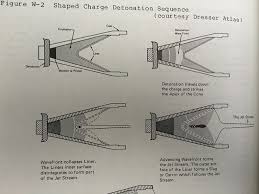

Shaped charges are designed to direct a detonation wave in a way that focuses  tremendous energy on a single spot, thus piercing even heavy armor. The principle is simple and enormously effective.

tremendous energy on a single spot, thus piercing even heavy armor. The principle is simple and enormously effective.

The illustration on the left shows a cutaway view of a classic shaped charge munition. You’re looking at a cross-section of a hollow cone of explosives. Imagine that you’re looking into an empty martini glass where the inside of the glass is made of cast explosive that is then covered with a thin layer of metal. The explosive is essentially sandwiched between external and internal conical walls. The open end of the cone is the front of the munition.

The initiator/detonator is seated at the pointy end of the cone (the rear of the munition), and when it goes off, a lot happens in the next few microseconds.  As the charge detonates, the blast waves that are directed toward the center of the cone combine and multiply while reducing that center liner into a molten jet that is propelled by enormous energy. When that jet impacts a tank’s armor, its energy transforms the armor to molten steel which is then propelled into the confines of the vehicle, which becomes a very unpleasant place to be. The photo of the big disk with the hole in the middle bears the classic look of a hit by a shaped charge.

As the charge detonates, the blast waves that are directed toward the center of the cone combine and multiply while reducing that center liner into a molten jet that is propelled by enormous energy. When that jet impacts a tank’s armor, its energy transforms the armor to molten steel which is then propelled into the confines of the vehicle, which becomes a very unpleasant place to be. The photo of the big disk with the hole in the middle bears the classic look of a hit by a shaped charge.

Now you understand why rocket-propelled grenades like the one in the picture have such a distinctive shape. The nose cone is there for stability in flight, and it also houses the triggering mechanisms.

Now you understand why rocket-propelled grenades like the one in the picture have such a distinctive shape. The nose cone is there for stability in flight, and it also houses the triggering mechanisms.

The picture on the right is a single frame from a demonstration video in which somebody shot a travel trailer with an RPG. The arrow shows the direction of the munition’s flight. There was no armor to pierce so the videographer was able to capture the raw power of that supersonic jet of energy from the shaped charge.

The picture on the right is a single frame from a demonstration video in which somebody shot a travel trailer with an RPG. The arrow shows the direction of the munition’s flight. There was no armor to pierce so the videographer was able to capture the raw power of that supersonic jet of energy from the shaped charge.

Another treasure to be saved and used later. I’m sure this discussion will be put to good literary use.

BTW, I’m still chuckling at the thought of an RPG hitting a travel trailer. It doesn’t sound fair, but it does sound entertaining.

So, when writing don’t misunderstand the fuse and the munition–which one goes where and which one goes first, right? Am I reading that correctly? Maybe it’s too early in the new year for me to be fighting fit. 🙂

Edward, I’m not sure I understand what you don’t understand. 🙂 The munition is the whole weapon, and the fuse is part of the ignition chain.

My fault, John. Sorry for the misunderstanding.

Read your two pieces looking for a lesson on writing. So, I thought I was pretty clever 🙂 when I saw that the two phases of a munition–the fuse and the main charge–were an extended metaphor which you were using to explain ‘foreshadowing’ as a writing technique. I interpreted the fuse as the foreshadow. I resisted trying to understand munitions as the purpose of your two pieces.

After reviewing the other comments, I think I was, too clever by half, looking for something (metaphor) that wasn’t intended. 🙂 Oh well, that’s a newbie for you.

The projectile hit the disk nearly dead center. If I understand the process that followed correctly, the energy from the explosion is concentrated in a near perfect cylindrical shape forward from point of impact to exit after linear passage from the disk, due to the thickness of the disk material (I can’t determine from the photo whether it is made of concrete or steel/iron), the composition of which must be dense enough to withstand the force of the energy from the explosion [which wants to move 360D perpindicularly to the projectile’s direction of travel] toward the disk circumfrerence edge (maybe I can write this more clearly if I review it tomorrow after a good night’s sleep). I’m not sure I’m stating a question so much as attempting to write an accurate description of a process. Am I close, omitting critical portions, all wrong?

Hi, Richard.

The disk is steel, and I think you were spot-on until the 360-degree perpendicular. You lost me there, because I’m not sure what that means. See if this helps clarify: The shaped charge does for detonation energy more or less the same thing that a parabolic mirror does for light energy. Just as a perfect parabolic reflector makes a dim light blinding by reflecting the light energy as a focused wave, the cone of the shaped charge reflects detonation pressure as a focused wave of super-heated, supersonic gas.

Have never blown anything up in fictional or real life. (Am afraid to uncork champagne bottles.) But if I ever do, I will take your advice to heart and find someone who knows what they are talking about! I do this with everything about guns, even though I have learned a lot over the decades of writing.

When writing about guns or explosives…don’t try this at home, children. 🙂

Thank you for the warning about cherry bombs and toilets.

May I ad another?

Never shoot a cherry bomb with a lit fuse up into the air using a sling shot, ESPECIALLY if the neighbors across the street have a balcony on the front of the house with a screen door, and the screen door was probably going to fall down, anyway.

May I add another tip? Never light a cherry bomb placed in a knot hole in a tree stump in the middle of a crowded park, on the Fourth of July, when said stump is surrounded by muddy wet grass after a rain, and when a very fat man is sitting in a nearby lawn chair sipping a large drink.

I love it! Safety first, everyone. Safety first. But deniability comes in a close second. 🙂

Mmmm…booms…me like booms..

Pingback: Writing Links in the 3s and 6…1/9/17 – Where Genres Collide