We are pleased to have a guest blog today by one of our regular participants, KAY DIBIANCA. Please check the bottom of this post for Kay’s background and links. Thanks, Kay, for agreeing to present this article.

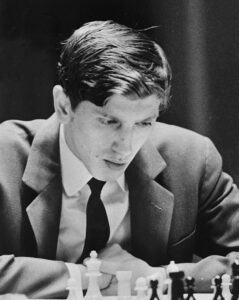

BOBBY FISCHER AND THE HERO’S JOURNEY

KAY DIBIANCA, AUGUST 2021

Recently I re-watched the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer. Although the story is based on the early life of a young American chess prodigy named Josh Waitzkin, the undercurrent is all about Bobby Fischer.

Fischer’s life was worthy of a Greek tragedy. Raised by a single mother, he received a chess set as a gift when he was six years old and the journey began. Fischer was amazing. Talented and obsessed with the game, he became the youngest ever U.S. Junior Chess Champion at thirteen and the youngest ever U.S. Chess Champion at fourteen. At age fifteen, he became the world’s youngest person to ever achieve the rank of international grandmaster.

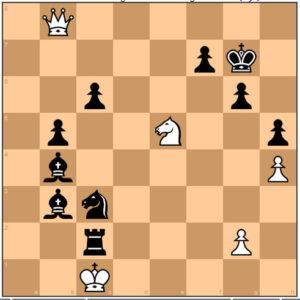

One example of his extraordinary skill was a game he played in 1956, in which he scored a remarkable victory over a leading American chess master, Donald Byrne, in what came to be known as The Game of the Century. Writing in Chess Review magazine, Hans Kmoch called it, “… a stunning masterpiece of combination play … “ Fischer was thirteen years old.

But like many great protagonists, Fischer had a personality of extremes. With an IQ measured at around 180, he had all the mental acuity of a genius – and all the charm of a horned toad. The world simply did not conform to Bobby Fischer’s standards, and he insisted on pointing it out. He railed against the Russians who had dominated the chess world for decades, accusing them of rigging the competitions by playing each other to easy draws so that they could reserve precious energy to play people from other countries. (He was right.) But his fury extended far beyond the chess board. He was rabidly antisemitic even though he was himself Jewish (through his mother), and he left a long trail of broken relationships and burned-out bridges behind him.

However, despite his many flaws, Fischer was so talented and hard-working that most people in the American chess world longed to see him compete for the world championship. As he was reaching his prime in the late 1960’s, it seemed the 1972 world championship would be perfect timing.

But the road to the 1972 World Chess Championship for an American started at the 1969 U.S. Championship. The top three finishers there would move on to the interzonal competitions, and the winner of those contests would compete for the title. However, because of disagreements with the organizing body, Fischer sat out the 1969 U.S. Championship making him ineligible for the later tournaments.

Then a miracle occurred.

In a culture not known for the humility of its participants, one of the U.S. Championship finalists, Pal Benko, stepped aside to give his hard-won spot to Bobby Fischer because he knew Fischer was the American with the best chance to beat the Russian superstar Boris Spassky.

Like Achilles returning to the field of battle, Fischer took Benko’s place and raged through the qualifying rounds, destroying all opponents. The extent of his winning streak was unprecedented, and he earned a higher rating than any player in history up to that time. More importantly, he won the right to meet Spassky in Iceland for the World Championship. The stage was set. It would be a classic cold war battle between the lone American and the Russian machine. Cue the drum roll.

But with the world eagerly awaiting The Match of the Century, Fischer balked. He wasn’t happy with the conditions in Iceland and he threatened to stay away, prompting Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to call and appeal to his sense of patriotism. Finally, after additional histrionics that rattled the chess establishment, Bobby Fischer sat down at the chessboard in Reykjavik and won the tournament by an impressive 12 ½ to 8 ½ score. He returned to the United States a conquering hero and was given a ticker tape parade in Manhattan. He was invited on television nighttime talk shows and feted by celebrities and politicians. Bobby Fischer had arrived.

But a flawed character cannot frolic in the rarified atmosphere of celebrity for long, and Bobby Fischer didn’t disappoint. He disappeared. Having lived so much of his life on sixty-four squares, he seemed unwilling or unable to move to a larger stage. Always reclusive and erratic, his behavior deteriorated and he refused to defend his title in 1975.

He did come out of hiding in 1992 and announced he would play an unofficial rematch against Spassky. But that match was to take place in Yugoslavia, a country on which the United States had imposed sanctions, and Fischer was advised by the U.S. that he would be breaking the law if he proceeded. Unsurprisingly, Fischer ignored the warnings, played the match, and won. Then the U.S. government, which had so lovingly welcomed him home twenty years before, issued a warrant for his arrest.

He never returned to America, but continued living abroad and dispensing his characteristic diatribes. In 2004 he was detained in a Japanese airport for using an illegal passport and jailed for several months. Iceland’s parliament stepped in and offered Fischer citizenship. He moved there in 2005 and died of kidney failure in Reykjavik in 2008.

If Bobby Fischer had been a polite, genteel man, he would still have been remembered as arguably the greatest chess player who ever lived. But would he have captured the imagination of the entire world if he hadn’t carried so much baggage? Would people have invested part of themselves in him if he had just quietly made his mark? I think not.

We are attracted to heroes who are complicated. They may thrill, shock, or disappoint, but they never bore us. They connect with life in a profound and mysterious way, and we’re like voyeurs, watching as they crest the ridge or wrestle the dragon. We applaud their triumphs, weep at their failures, mourn their loss, and in the end, we acknowledge and value the impact they have had on us.

“What is chess, do you think? Those who play for fun or not at all dismiss it as a game. The ones who devote their lives to it for the most part insist that it’s a science. It’s neither. Bobby Fischer got underneath it like no one before and found at its center, art.” Ben Kingsley in the role of Bruce Pandolfini in “Searching for Bobby Fischer.”

So TKZers. What flaws does your protagonist have? Will he/she conquer them, succumb to them, or just manage to get through and live to fight another day?

***

I am deeply grateful to Steve Hooley for inviting me to guest post, and to all the TKZ community for the information and inspiration I have found on this site over the years.

Kay DiBianca is a former software developer and IT manager who loves to create literary puzzles in the mystery genre for thoughtful readers to solve. Her debut novel, The Watch on the Fencepost, won a 2019 Illumination Award for General Fiction and a 2019 Eric Hoffer Award for Mystery. Her second novel, Dead Man’s Watch, was released in 2020.

An avid runner, Kay can often be found at a nearby track, on the treadmill, or at a large park near her home. Kay and her husband, Frank, live, run, and write in Memphis, Tennessee.

You can connect with Kay through her website at https://kaydibianca.com.

Jennifer Pound is a recently retired police officer where she thrived in various traditional and non-traditional policing roles. She spent years as the face of the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police) as a communications director. Her recent role was with IHIT, Vancouver’s Integrated Homicide Investigation Team — the largest homicide unit in Canada — where she saw the worst of people and helped to bring justice for the victims that died at the hands of evil.

Jennifer Pound is a recently retired police officer where she thrived in various traditional and non-traditional policing roles. She spent years as the face of the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police) as a communications director. Her recent role was with IHIT, Vancouver’s Integrated Homicide Investigation Team — the largest homicide unit in Canada — where she saw the worst of people and helped to bring justice for the victims that died at the hands of evil. Many police officers think the absolute worst; it’s a gift we’ve so graciously received, or perhaps more like a curse. Few of us can drive by a bag of garbage or a rolled-up carpet on the highway and not think about the nightmare that must live within. I’ve often wondered if it was just me, but I know with certainty, it’s not.

Many police officers think the absolute worst; it’s a gift we’ve so graciously received, or perhaps more like a curse. Few of us can drive by a bag of garbage or a rolled-up carpet on the highway and not think about the nightmare that must live within. I’ve often wondered if it was just me, but I know with certainty, it’s not.

To test the theory, she made a bit of a detour. She turned down a cul-de-sac with few homes that only residents that lived there would need to access. She walked for a bit and then did an about-face, like she forgot something, crossed the road, and turned back. Hub cab carrying, douchebag guy continued to follow them. At this point, she was terrified. She grabbed her sister’s hand, and she ran. They ran until they reached the school and she lost sight of him. That’s when she called me.

To test the theory, she made a bit of a detour. She turned down a cul-de-sac with few homes that only residents that lived there would need to access. She walked for a bit and then did an about-face, like she forgot something, crossed the road, and turned back. Hub cab carrying, douchebag guy continued to follow them. At this point, she was terrified. She grabbed her sister’s hand, and she ran. They ran until they reached the school and she lost sight of him. That’s when she called me.

Just a few weeks ago I began my first real foray into the world of Instagram for my art work (BTW I’m @clangleyhawthorneart if anyone’s interested:)) and I feel like I’m definitely in the ‘Instagram for Dummies’ phase! Bizarrely – since I’m only focusing on my art there – I seem to have discovered a whole lot of book and writing related pages so rather than being focused on my own work I’ve been salivating over beautiful photographs of libraries and book covers instead:). As with any new social media experience, I’m still in the throes of wonderment (which won’t last long – no doubt I’ll soon be getting the trolls and the weird follows from fake men!) but also in the thick of trying to work out how the heck to use it. So far I’ve really only managed to upload photos…

Just a few weeks ago I began my first real foray into the world of Instagram for my art work (BTW I’m @clangleyhawthorneart if anyone’s interested:)) and I feel like I’m definitely in the ‘Instagram for Dummies’ phase! Bizarrely – since I’m only focusing on my art there – I seem to have discovered a whole lot of book and writing related pages so rather than being focused on my own work I’ve been salivating over beautiful photographs of libraries and book covers instead:). As with any new social media experience, I’m still in the throes of wonderment (which won’t last long – no doubt I’ll soon be getting the trolls and the weird follows from fake men!) but also in the thick of trying to work out how the heck to use it. So far I’ve really only managed to upload photos…