by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Gather round for another of our first-page critiques. The genre is Mystery. My comments to follow.

Gather round for another of our first-page critiques. The genre is Mystery. My comments to follow.

A litter of russet leaves curled over the hood of the taxi as it pulled up to the curb. Chad had accepted a lift from the airport from Claude Durand, and now he was regretting it.

“I think it’s braveof you, to support Follett publicly,” Claude said.

Chad avoided eye contact. Was it brave to be honest? It shouldn’t be.

“Mind you, I wouldn’t stake your reputation on his. After what he did—”

“What he did? You mean what was done to him.”

Claude raised his palms. “Ecoutez-moi. I think you will find that many people at this tournament lost money when they invested in Chess Maestro.”

“An investment is always a risk.”

Claude surveyed him coolly. “You probably think you’ll be winning chess tournaments for the rest of your life.” With an extra tang of bitterness, he added, “Nice to be young.”

Outside the car window, the seaside hotel soared into the blue September sky. And on the front steps stood David Follett, with a fedora pushed back on his head and his chin raised.

“Well,” Chad said half-heartedly. “Thanks for the heads-up.”

Claude raised a palm again. “I’ve been studying your moves. You’ve got possibilities.” He put his hand on the door handle. “Don’t waste them.”

Chad left the car. He loved playing chess more than anything else in life. But he wasn’t always sure how he felt about other chess players.

“Good to see you, brother,” David said, crossing over to shake hands with him. “D’you have a good trip?”

“All but the lecture at the end.”

David grinned, showing the wrinkles around his eyes. “I’ll bet. But on a day like this, I feel magnanimous with the whole world. Even the Claude Durands. I think this is going to be a good tournament. You?”

“I’m feeling good.”

“That’s it, brother. Don’t let it all get to you. It’s just about the fun of the game.”

As Chad turned away, David placed a hand on his arm.

“Remember, the most dangerous game you’re playing is the one in your head.”

David Follett was always saying cryptic things like that. Chad never really understood what they were supposed to mean, but this time the words would come back to him with cruel significance before the day was done. David would be found floating face down in the hotel pool, his final game all played out.

***

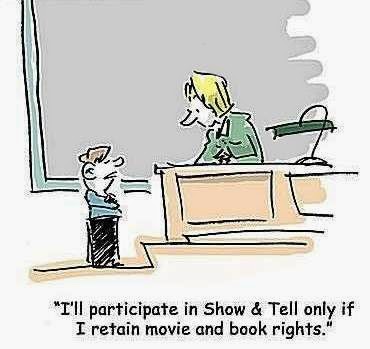

JSB: Let’s start at the end. You hear it over and over: show, don’t tell. There’s good reason for that—it works. It’s the difference between an immediate, emotional experience (which is what a reader craves) and a dull lecture.

Yes, there are times to tell, but almost always that is in order to get from one scene to another quickly, so you can start showing again.

And for goodness’ sake, always show the most important, emotion-charged part of the scene in all its vividness.

Here, the most interesting thing that happens on the page is the body floating in the pool. But we’re only told about it. Worse, it hasn’t even happened yet, taking all the potential of emotional impact out of it when it does.

Dead bodies must be shown or reported in real time. (Unless they are part of a character’s backstory.)

So my first bit of advice for our writer is to cut something: the last paragraph.

Now let’s go to the beginning.

A litter of russet leaves curled over the hood of the taxi as it pulled up to the curb. Chad had accepted a lift from the airport from Claude Durand, and now he was regretting it.

That first line doesn’t give us a POV. It’s just there. Who is seeing these leaves?

Apparently Chad, according to the second line. Except the second line is written in the past tense, then switches to the present. This is confusing. Make a note of this: your opening page should always be present tense action through one POV. That will never, ever hurt you. Once you become world famous, you can mess around with style if you wish. But I wouldn’t advise it.

Oh yes, and avoid giving characters names that start with the same letter. It’s too easy to confuse Chad and Claude.

“I think it’s brave of you, to support Follett publicly,” Claude said.

I wouldn’t italicize “brave” in this instance. In fact, don’t italicize dialogue unless it’s necessary for emphasis, e.g., “I can’t believe you let him kiss you!”

Chad avoided eye contact. Was it brave to be honest? It shouldn’t be.

“Mind you, I wouldn’t stake your reputation on his. After what he did—”

“What he did? You mean what was done to him.”

You’re introducing a note of mystery here, which is a good move. And look! Italics might be called for, i.e., “What he did? You mean what was done to him.”

Claude raised his palms. “Ecoutez-moi. I think you will find that many people at this tournament lost money when they invested in Chess Maestro.”

I can’t think of a good reason to have Claude saying, Ecoutez-moi. Unless someone speaks French rather well, it just looks odd. I know it characterizes Claude as something of a continental sophisticate, but you can do that in other ways.

Claude surveyed him coolly. “You probably think you’ll be winning chess tournaments for the rest of your life.” With an extra tang of bitterness, he added, “Nice to be young.”

Okay, here is the first indication of who is who and what is what. Chad is a young chess master. Fine. But who is Claude? What is Claude’s relationship with Chad? Why should Chad listen to him?

Outside the car window, the seaside hotel soared into the blue September sky. And on the front steps stood David Follett, with a fedora pushed back on his head and his chin raised.

Again, that first sentence is passively objective. Put it in Chad’s head. Have him seeing the hotel. And by the way, where are we? Sounds like France, but this is where you can add specificity so the reader knows we’re at, say, the Soufflé Puant Hotel.

Chad left the car. He loved playing chess more than anything else in life. But he wasn’t always sure how he felt about other chess players.

Okay, here’s the heart of the matter. What’s missing in this scene is a character to bond with and a disturbance. Those are two crucial elements of any first page. The first question a reader has is, Who am I reading about? Whose story (or at least chapter) is this?

The second question is, Why should I care?

We’ve covered the first issue. Firmly establish we’re in Chad’s POV, and stay there. But further, what is there about him that we can empathize with? His love of chess might work, but the problem is you tell us he loves it. We need to feel him feeling it.

Here is where a bit of backstory can help. You’ll sometimes hear a critique-group sheriff announce in no uncertain terms, “No backstory in the first thirty pages!” This is not good advice.

There is fair warning about too much, however. So what’s the answer?

I’m here with JSB’s Backstory Prescription (JSBsBP). I’ve given this to students many times with wonderful results.

- In the first ten pages (approx. 2500 words) allow yourself three sentences of backstory, used all together or separately.

- In the second ten, three paragraphs of backstory, all together or separately.

So here on the first page, give us some blood pumping in Chad about chess, such as:

Ever since he was seven, when his dad taught him the moves, Chad had been in love with chess. When he starting playing tournaments at age eight, the joys of victory deepened his love into a devotion bordering on obsession.

Now we’re starting to bond. What will cement that bond is a disturbance.

What trouble is there? Chad is arriving for a chess tournament of some sort. Claude tells him he’s being “brave.” You tell us he isn’t sure about some of the other chess players. David tells him not to “let it all get to you.” That’s not enough.

Give us something specific Chad can worry about.

- Death threats.

- Being charged with cheating.

- A female chess player who dumped him is going to be there.

- He’s experiencing sudden fatigue or anxiety.

Brainstorm. Come up with something that tells us it’s not smooth sailing arriving at this plush resort for a tournament.

Whew. I think I’ll stop here in order to make a suggestion. Try writing this first page in all dialogue. Not even attributions. This is for you only. Figure out how to put in all the crucial information we’ve talked about in a tense dialogue exchange between Chad and Claude. Include the disturbance in this exchange. (See my post on hiding information inside confrontation. See also P. J. Parrish’s Dos and Don’ts of a great first chapter.)

After that’s done, drop in two or three sentences of backstory, as prescribed earlier.

You’re going to love the result. As will potential readers.

And then—keep writing!

Good luck.

Comments welcome.