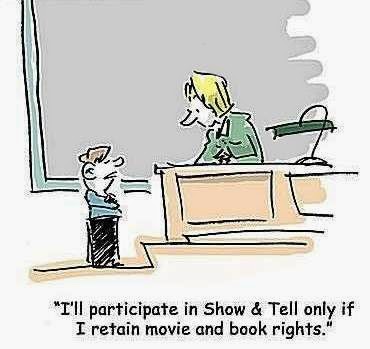

How many times have we all heard this: SHOW DON’T TELL!

I put it all in nice bright letters because those three words are so commonplace in writing workshops that shoot, we might as well put them in neon, right? Ask a writing coach or an editor what the cardinal sin of bad writing is and “telling” is right up there with procrastination. We really get our panties in a wad about it. But let’s stop and take a deep breath here

((((Breathe in pink, breathe out blue…)))

and figure out what SHOW DON’T TELL really means.

Okay, let’s start with a definition because it’s always good to start with specifics.

Show don’t tell means writing in a manner that allows the reader to experience the story through a character’s action, words, thoughts, senses, and feelings rather than through the narrator’s exposition, summarization, and description. The idea is not to be heavy-handed, but to allow issues to emerge from the text instead.

(((((ZZZzzzzzzz))))

Boring but necessary physical action

Pure description

Backstory

The first image that usually came to him when other people started talking about their childhood was a house. Other things came, too. Faces, smells, emotions, mental snapshots of events. But those kinds of memories were fluid, changing for good or bad, depending on how, and when, you chose to look back on them.

But a house was different. It was solid and unchanging, and it allowed people to say “I existed here. My memories are real.”

His image of home had always been a wood frame shack in Mississippi. It was an uncomfortable picture, but one he had held onto for a long time, convinced it symbolized some kind of truth in his life about who he was, or what he should be.

Okay, so show me already!

Shadows closed around him as the sun played hide-and-seek behind dark clouds. Thunder rumbled in the distance. Impending rain scented the air. Spanish moss fluttered in a sudden breeze that carried with it the cloying acridness of the swampy bayou.

And at his feet in the vermin-ridden humus lay a young woman. A woman who, until a day or two ago, had hoped, planned, and dreamed. Maybe even loved.

Now she lay dead. Violently wrestled from life before her time. And it was his job to find her killer.

He started when, with a flap of wings, a snowy egret soared into the air twenty feet in front of him. As the regal bird disappeared from sight, Kramer couldn’t help but wonder if maybe it was his Jane Doe’s soul wafting to the Land of the Dead. The way the dove in Ulysses had carried Euripides’ soul.

Despite the day’s heat, a chill seeped through him. Instinctively and unselfconsciously, Kramer crossed himself and wished her soul Godspeed.

Here’s a rewrite of the same scene:

Shadows closed around him as the sun played hide and seek behind dark clouds. Distant rain scented the still air and Spanish moss hung like wet netting on the giant oaks. The cloying acridness of the bayou was everywhere.

Kramer wiped the sweat from his brow and looked down at the dead woman and drew a shallow breath .

She was the third young woman this year who had been left to rot in the muddy swamps of Louisiana.

With a sudden rustle of leaves, a snowy egret soared into the air twenty feet in front of him. Against the slanting sun it appeared little more than a ghostly white blur but still he watched it, oddly comforted by its graceful flight up toward the clouds.

Then, with a small sigh, he looked back at the woman, closed his burning eyes and crossed himself.

“God’s speed, ma cherie,” he whispered. “God’s speed.”

Why does the second one work better? Why does it hit our emotions harder? Because the writer got out of the way and let the character’s actions and words move the story along.

Here’s example 2. This is the opening of chapter 1 and the setup is a woman overseeing a parade at Disney World. It’s long but it’s worth analyzing.

Dorothy Gale got it wrong. Even as a kid, I didn’t understand why she was so hell-bent to hustle herself out of Oz to return to Kansas. Was she crazy? I ached to leave ordinary behind and devoured every magical Frank Baum book in the library. When I was nine, I vowed I’d find the Emerald City one day and I did. The Wizard—or rather Orlando’s theme park industry—set a shiny, incredible Land of Oz at the end of my personal yellow brick road.

Ten years ago, with a fresh college diploma—Go Terps—I’d found my niche and myself when I snagged my first job at Oz. Work felt like play in my fairytale world. And my disappointed parents stopped blaming themselves for those library trips when Oz promoted me to assistant department manager for process improvement. Tonight, we were rolling out a new parade, and for me, the excitement rivaled Christmas Eve.

Churning the humid Florida air, the dancing poppies whirled by in a swirl of red, plum, and purple, so far a flawless debut. Across the Yellow Brick Road, my boss Benjamin flashed me a rare smile and gestured to his stopwatch. The lilting music gave way to the recorded yipping of hundreds of puppies, and forty employees pranced by in shaggy-doggy costumes. Toto’s enormous basket-shaped float reached the corner, and excited children squealed, adding a thousand decibels to the noise.

“Slower, Toto,” I murmured into my mouthpiece. “Turn on three.” I counted and the basket’s driver, hidden deep inside the float, turned with inches to spare.

Here’s how I would handle it.

The red and pink poppies danced in the humid Florida air. The lilting music gave way to the recorded yipping of hundreds of puppies, and forty employees pranced by in shaggy-doggy costumes. Toto’s enormous basket-shaped float reached the corner, and excited children squealed, adding a thousand decibels to the noise.

Across the Yellow Brick Road, my boss Benjamin flashed me a rare smile and gestured to his stopwatch. So far, it was a flawless debut. I pressed my clipboard to my chest and smiled.

God, how I loved it here.

My own fairy tale world.

My own private Oz.

“Slower, Toto,” I murmured into my mouthpiece. “Turn on three.” I counted and the basket’s driver, hidden deep inside the float, turned with inches to spare.

My own parade – every day.

Dorothy got it wrong. Even as a kid, I never understood why she was so hell-bent to get out of Kansas.

In a large pantry off the kitchen, I found the maid. She, too, was dead. From the marks on her neck, my guess was someone had strangled her. As I completed my trip around the downstairs, I heard a noise from the front of the house, then a call of, “Police. Anyone here?” I took a deep breath and started toward the front room.

The cops met me in the hall with the obligatory order to drop my weapon and assume the position against the wall. I complied and a young patrolman named Johnson explored areas I preferred not touched by a stranger. However, I understood. I’d have done the same if I had found anyone during my search, and I wouldn’t have concerned myself about his or her privacy.

Once he finished, I showed my PI credentials.

In the rewrite, I converted the “tellling” into “showing,” mainly by handling things in dialogue.

In a large pantry off the kitchen, I found the maid. She was face down on the marbled floor, arms splayed, feet part, still dressed in her baby blue cotton uniform. I knelt and when I moved her thick pony tail, I saw a tattered clothesline wrapped tight around her neck. She had no pulse. It hit me that I met her three times on previous visits and yet I could not remember her name.

“Police! Anyone here?”

I turned toward the echo of voices, toward the long cavernous hallway that led to the living room. Before I could take a step, I felt a jab of steel against my temple and someone’s hot breath in my ear.

“Against the wall, lady.”

“But —”

“Shut up,” the cop said as he patted around my ass for a weapon. He found my gun, ripped it from its holster and roughly turned me around. I didn’t know the officer in front of me but I saw Sgt. Randy Rawls standing in the doorway, trying not too hard to stifle his snicker.

“She’s okay, Jim,” he said. “Her name is Jenny Smith. She’s a local P.I.”

One more example but it’s one of my favorites. The setup is a TV anchorwoman looking forward to meeting her boyfriend after work. I like it because the writer was so close to getting it right. But he needed to focus in on what I call special details and actions that show (ie illuminate) character.

Tonight, however, Corrie was looking forward to dinner with Jake.

Jacob “Jake” Teinman employed a wicked, take-no-prisoners wit. She found his sense of humor engaging, and delighted when he would elevate one eyebrow while keeping the other straight alerting his target to an oncoming barb. Corrie truly liked Jake, a lot, but experience taught hard lessons and she had qualms about the two of them as a couple.

They were awfully different — she: a public persona, trim, career driven, self-centered, frenetic and Irish Catholic; he: private, stocky, successful with a controlled confidence that drove her nuts, and Jewish. At least that’s how she pictured the two of them. She wondered if Jake’s version would agree.

She’d noted they’d been dating exactly one year and he had made reservations at “The 95th” just six blocks from the WWCC studios. It was sweet of Jake since he knew it was one of her favorite places.

Tonight, Corrie was looking forward to dinner with Jake. And as she watched him come in the restaurant door, she smiled. It used to annoy her when people said how different they were. But it was true.

Jake…

Stocky. Dark. Jewish. Coming toward her with that confident swagger.

And her…

Tall. Blonde. Irish-Catholic. Sitting here wondering if he’d show up.

He kissed her on the cheek and sat down.

“You remembered,” she said.

He frowned. “Remembered what?”

“That this is my favorite restaurant.”

He glanced around before the puppy-dog brown eyes came back to hers. “Sure, babe,” he said. “I remember.”

What’s the main problem with the first one? The “telling” is slow-paced and un-viscereal. And if the guy just went through a plate glass window he probably can’t see the glass falling and it sure as heck wouldn’t register in his senses as “glittering shards” and “fading fireworks.” In the second version, the POV is fixed and every detail that IS possible is filtered through the man’s senses.

- Narrating the physical movements without being in character’s head.

- Use of too many ‘ly’ words in action or in dialog (i.e. She said impatiently, walked slowly, yelled angrily.)

- Use of stock descriptions, purple prose or lengthy descriptions of places (and people) especially those that have no bearing on the plot.

- Too many adjectives and cliches.

- Omniscient POV (distancing, describing from an all-seeing POV) The man getting hit on the head cannot see the glass as it falls six stories to the ground.)

- Action that uses the senses, stays within the character’s consciousness and uses words and phrases that reinforce the mood of the scene.

- Strong verbs. (Walked vs Jogged, Ran vs Raced, Shut the door vs Slammed the door.)

- Original images and vivid descriptions that are filtered through the character’s senses in the present.

- One compelling adjective vs. a string of mediocre ones.

- Keep POV firmly in character’s head. (Establishes sympathy and connects emotionally.)

The Show Don’t Tell concept seems to be one of the most confusing “rules” to beginning writers. I wish they could all read your blog today, and reread it tomorrow. Great job, Kris.

Ditto, what Joe said. Great real examples here. Now if only there was a Scratch & Sniff app for the pizza & wine.

I have a “tell” tic that trips me up every damn time. Even in 1st POV, I tend to say, “I felt the raindrop hit my cheek,” rather than “The first raindrop was cool on my cheek.” Other than that, sometime you just have to get the character out of bed and out the door.

When I inherited my nano-press, I also inherited a self-pubbed serial novel that had been running, chapter at a time, for a couple of years. It is dreadful, but I promised to complete it.

It will digress off into 2-3 page backstory rambles telling me about a character. It pains me to type it every month, but I promised.

Terri

I haven’t done much first person, Terri, but when I tried it, I had the same problem…lots of “felts” “had the feeling that…” It requires a certain brain shift to write well in first, I think.

Wow. Just wow. You really told them. Or showed them. One hell of a blog, Kris.

This article is pure gold, Kris! You really know how to teach writing craft – clear explanations and great examples, written in an entertaining style! Perfect. As Elaine said, “Wow. Just wow.” I’ll be sending all my clients here to read this!

And may I quote your excellent definition, with full credit to you of course, in my next book? I love this:

“Show don’t tell means writing in a manner that allows the reader to experience the story through a character’s action, words, thoughts, senses, and feelings rather than through the narrator’s exposition, summarization, and description. The idea is not to be heavy-handed, but to allow issues to emerge from the text instead.”

Jodie: You can quote it but it’s not mine and I don’t remember where it comes from, alas.

Going to critique group folks…will check in soon!

PJ, first time I’ve commented here. Feel just like I just went to the best conference in the world on a favorite subject. Bet I can write a long e mail message than you.

Glad to have you speak up RG! Thanks for the kind words.

Great post!

I have a friend who runs a great blog called The Other Side of the Story who thinks almost all issues of a book can be solved through POV. In each of your examples, not only did we feel more though being shown what was happening, the pacing was better, and the writing itself was less cumbersome.

The biggest struggle I have with Show vs. Tell is figuring out if that extra bit of information is cool/interesting enough to justify it’s existence.

A lot of your first examples were over written, with the powerful sentences buried among other lesser details, but occasionally there was a detail that was considered telling, but I still loved anyway. In your first example, the “Show” version still hinted at the egret being the girl’s soul, in an incredibly powerful way. But I also liked how the first version specifically mentioned the land of the dead and the dove that carried Euripides.

It’s a judgement call that can be hard to make. God bless beta readers and editors. 😀

Thanks for such a thorough look the subject!

Good points, Elizabeth. Yes, sometimes it can be a matter of style. Mine is more spare than a lot of folks but I am a strong believe in less is more. And yes, it is difficult to tell where the line is between evocative and underwritten.

As I grow in my craft, I find myself favoring more spare prose and lots of subtext over going all out with the description, too. I tell myself it’s because I’m getting better. 😀

Excellent examples. Showing the story gives immediacy to a tale and is so much better at grabbing the reader’s interest. Being a Disney fan, I liked your theme park Oz passage.

His smile grew wider as he read on. The examples she gave seemed, well, OK. Then the rewrites — it was like those pictures where something was right in front of you but you couldn’t see it. Then after you spotted it, it seemed laughingly obvious.

“Wow,” he said, nodding over and over. “Wow.”

Frank: When I first started teaching writing (decades ago in a library course), I struggled to get points across because technique is difficult to articulate sometimes. It hit me that before and after examples SHOW so much more than I could ever TELL.

We had an assignment in one of my writing classes and the instructor asked that we use one or two paragraphs to tell about something. When she then asked us to show those same two paragraphs using our 5 senses, the two paragraphs turned into two pages! 🙂

But, I have to say, the transformation was amazing!

That’s an interesting assignment. Must remember that, Diane. Good muscle-stretcher.

This is by far the best post I’ve read about “show don’t tell”. You are a great teacher. However, it’s not as easy as this in 1st POV, which is what I usually write in. Sometimes you just need to say, “I felt a sheen of sweat on my face.” because obviously the POV character can’t see it. Sure, you can say, “I wiped the sweat from my forehead.” But how many times can they actually do that? There’s a point where it sounds unnatural and awkward.

Sue, I have often said that I think first person POV is more difficult, mainly because your options are so limited that it is almost impossible to avoid the occasional clumsy construction or even cliche. First POVers have to work harder to build a believable sensory universe EVEN THOUGH they are literally living in the protag’s head. I wrote several short stories before I wrote a full length First POV novel and I found it exhausting. But exciting, in an odd way, to be that close to my character. I wrote a second thriller in first AND third POVs….that was a real challenge.

This comment has been removed by the author.

This comment has been removed by the author.

I am in the midst of cutting out all the ‘show’ I can from my WIP. My main reaction as I go through edit #3 is “Wow…I wrote that like that?”

facepalm, sigh, “I hope no one else saw this.”

Basil, when Kelly and I went back and edited our first Louis book, “Dark of the Moon” for eBook publication, we had the same reaction. We are still working on it. We have cut 80 pages so far. And this book got published by reputable house.

This is one of the cleanest, most sensible explanations of the term I’ve heard. Thank you for making it practical.