Jordan Dane

@JordanDane

Recently I’ve been writing characters with unique regional accents or characters that I’ve had to invent how they speak, because they are unlike any other character I’ve ever written. When you create a character like this, you have to work doubly hard to “see” them and “hear” them in your mind.

Listen to real conversations. I especially love eavesdropping on teens, but as writers it is fun to be a snoop and hear the way people express themselves and their cadence. People often speak in fragments and laugh at one word asides. They launch into a diatribe and get interrupted by someone else. How do they react? If they come from a large family, I have a pretty good idea how they would react. But if they are an only child, do they retreat until the blustery winds of a blowhard die down?

It’s important to not only hear authenticity, but to also visualize it, without losing the fluid flow, pace, or clear plot points conveyed. Fictional dialogue must have a point, too.

1.) How well do you know your characters?

• Does it take you some writing time to get to know your characters? A good exercise is to write your character in first person to take them for a test drive, to get a feel for who they are and what matters to them.

• Live in their skin for awhile. Imagine what they look like, what they would wear. Create a photo image board from internet searches to flesh them out –in posture, eyes, attitude, swagger, dialect, education, job, sense of humor, etc.

• When you have a good feel for your main character, pair them with other fictional sidekicks or antagonists who will argue with them or cause conflicts and friction.

• Be careful to minimize slang or poorly spelled words or lots of bad grammar. Readers might have a problem with dialogue that is difficult to read throughout a book, but a smattering of regional color can be just the ticket to setting your world stage.

2.) Imagine Playing Your Character on Stage

When I “hear” voices in my head (from my characters, that is), especially if I’ve written them with accents or attitudes, it is fun to act them out. Do this by reading aloud and embellishing with your thoughts on how they sound. Reading aloud helps catch edit issues, but it can also help you create a cadence suitable for your character and give you insight into who they are.

Whenever I do readings at book signings (which I LOVE to do), I really get into the reading and become the character. I sometimes have my attendees close their eyes to focus on the story and trigger their imaginations, forgetting that they are in a bookstore. Often you can hear a pin drop when I finish and you get the real reaction from those listening when they open their eyes and return to the present from where they’ve been. Who knows? Acting out your character can help you “see” them in your mind – how they move or do hand gestures.

3.) In action scenes or tension packed scenes, make the dialogue sound real.

As an author would shorten narrative prose to give the reader the feeling of tension, suspense, and danger, it’s best to use short, concise sentences to enhance pace. Each line is like a punch in the gut to give the reader a visceral reaction to the change in pace.

Some passages may have longer lines of explanation or technical plot essentials, but keep those to a minimum if you want pace to lead the way. An expert in a dangerous situation would not suddenly turn into Mr Wizard to explain everything. They might get impatient and find a quick example or way of speaking to get their point across, while showing their frustration. How do they react under stress will show in their dialogue.

A long back and forth with punchy short sentences can let the reader sense the mounting tension, but if it goes on too long, it can get old, fast.

Excerpt: The Darkness Within Him (Amazon Kindle Worlds)

When a startling vision triggered a memory Bram Cross thought he’d buried, an icy shard carved through his body The macabre and haunting face of his mother lurched from the pitch-black of his mind—her eyes, what she did.

No, I can’t do this. Don’t make me. He fought hard to stifle his childish, irrational refusal, but he had to say something.

“You’re an asshole. We shouldn’t be here,” Bram said. “Someone’s watching us. I can feel it.”

“Shut up. You’re paranoid,” Josh spat. “You said you’d come with me. Quit your whining.”

“Something’s not right.”

Josh stopped, dead still, at the mouth of the infamous tunnel. He stood on the spot where the mutilated, half-eaten bodies of dead rabbits had been found in 1904—killed by ‘Bunny Man,’ an insane prison escapee named Douglas Grifon. The bad omen made Bram step back, but too late. By sheer stupidity and bad luck, Josh had jinxed them both.

Josh glared at Bram as he reached into a pocket of his jacket.

“I brought insurance, courtesy of dear old dad. We’ve got nothing to worry about.” He pulled out a gun and grinned as if he had all the answers.

“Are you insane? Put that away.” Bram fumed. “I’m out of here. I didn’t sign up for this.”

Bram turned to go, heading back toward the car that Josh had parked at the trailhead, but his friend grabbed his arm.

“You’re not going anywhere. I’ve got the car keys. Man up, shit for brains.”

4.) Dialogue should intrigue and draw reader in. Don’t use it to explain or the lines fall flat.

Dialogue should enhance the action and add to the emotion and pace. If you take the time to explain an action, the dialogue will sound contrived. If you explain what the characters should already know, why are you doing it? Savvy readers know when the dialogue is meant for them and when it doesn’t add to the story, but detracts from it and slows the pace.

Think of endings where the villain goes through lengthy explanations to “tell” the reader what the book has been about. Old mystery formats are like this where Sherlock Holmes expounds on how clever he is by detailing “who done it.” If a certain amount of this is necessary, make it about a mind game between the hero and villain where they have a reason to “one up” the other with reveals, but keep it to a minimum and not at the expense of good dialogue.

5.) Interruptions can be good in dialogue.

Interruptions can focus a character, keep up the pace, or show a realistic way to direct the reader where you want them to do. Have your characters ask questions of each other to liven things up.

Excerpt – The Darkness Within Him

Ryker Townsend – FBI Profiler

After the kid undid the latch and the deadbolts, he opened the door enough for me to see the injuries he’d sustained in his fight with Mr. Whitcomb. Josh stared at me for a split second before he shoved the door closed, but I jammed my foot in the opening.

“Police. We just want to talk.” I pushed through the breach and he winced. “Are you Josh Atwood?”

He didn’t answer and backed into a small living room. Reggie and Jax walked in behind me.

“Hey, aren’t you supposed to show ID?”

I eyed Reggie and the detective indulged him with a show of his badge.

“But I didn’t invite you in.”

“That only works with vampires. Consider this a welfare check, Bueller.”

6.) Add tension in Dialogue by making your characters hesitate or stall.

Is one of your characters in charge or forceful? How does that manifest in the other character in the scene? Often dialogue is like a chess game where one person tries to outwit the other or get the upper hand.

When one character stalls or shuts down, and the conflict grows, that can read as very authentic. We all have little voices in our heads, especially when we are dealing with arguments or confrontation. Effective dialogue must have nuances like a dance choreography that flows naturally and reads as effortless. When the scene starts out, one character can suddenly change course. How would you reflect that? Conflict is always interesting.

7.) Cut out the unnecessary and keep your dialogue vital. No chit chat.

I often write dialogue first, like in a script, to flesh out the framework of a scene. Later I fill in the body language, action, internal monologue, but dialogue is vital to make the scene hold up. It’s what the reader’s eye will follow on the page. When I edit, I will tighten dialogue lines, especially in action scenes, to keep the lines flowing naturally.

8.) Punch up the dialogue with action or character movement in the scene.

Give the reader something visual to imagine as they read your scene. All dialogue scenes, where two characters sit at a table, can be mind numbing and boring. Make the scene come alive by giving them something to do, especially if it puts them at odds with each other. Make that action unexpected, like adding sexual tension in the scene below (excerpt from Elmore Leonard).

Even if you MUST put them at a table, give them something to do. I especially like body language where it’s obvious the characters are hiding something and have let the reader in on that fact. Or punch up a funny line with a physical habit to accentuate humor or give distinction to a character.

9.) Minimize tag lines and give characters unique dialogue so tags aren’t as necessary.

One of my edit reviews is looking at tag lines to eliminate ‘saids.’ I often replace a said with an action that attributes which character delivered the line.

Also keep in mind, if you have a number of characters in a scene, a well-placed ‘said’ can orient the reader and ID the character in a scene where it’s easy to get lost. Gender oriented lines can help distinguish characters, or the regional dialect, or even if one character has a certain type of humor. ‘Said’ is the kind of word that disappears in a reader’s mind, but if you string too many together, it’s like sending up a flare “NOTICE ME!”

10.) Reading authors who write excellent dialogue is important.

Real pros at dialogue make it look effortless. Get schooled. If an author makes dialogue work, try to understand why it works and how you can infuse that in your own style and voice. Here are a couple of examples:

Elmore Leonard Excerpt – From Out of Sight (U S Marshal Raylan Givens) – I can imagine this very visual scene with the sexual tension.

‘You sure have a lot of shit in here. What’s all this stuff? Handcuffs, chains…What’s this can?’

‘For your breath,’ Karen said. ‘You could use it. Squirt some in your mouth.’

‘You devil, it’s Mace, huh? What’ve you got here, a billy? Use it on poor unfortunate offenders…Where’s your gun, your pistol?’

‘In my bag, in the car.’ She felt his hand slip from her arm to her hip and rest there and she said, ‘You know you don’t have a chance of making it. Guards are out here already, they’ll stop the car.’

‘They’re off in the cane by now chasing Cubans.’

His tone quiet, unhurried, and it surprised her.

‘I timed it to slip between the cracks, you might say. I was even gonna blow the whistle myself if I had to, send out the amber alert, get them running around in confusion for when I came out of the hole. Boy, it stunk in there.’

‘I believe it,’ Karen said. ‘You’ve ruined a thirty-five-hundred-dollar suit my dad gave me.’

She felt his hand move down her thigh, fingertips brushing her pantyhose, the way her skirt was pushed up.

‘I bet you look great in it, too. Tell me why in the world you ever became a federal marshal, Jesus. My experience with marshals, they’re all beefy guys, like your big-city dicks.’

‘The idea of going after guys like you,’ Karen said, ‘appealed to me.’

John Steinbeck – Of Mice & Men

‘Tried and tried,’ said Lennie, ‘but it didn’t do no good. I remember about the rabbits, George.’

‘The hell with the rabbits. That’s all you ever can remember is them rabbits. O.K.! Now you listen and this time you got to remember so we don’t get in no trouble. You remember settin’ in that gutter on Howard street and watchin’ that blackboard?’

Lennies’s face broke into a delighted smile. ‘Why sure, George, I remember that…but…what’d we do then? I remember some girls come by and you says…you say…’

‘The hell with what I says. You remember about us goin’ into Murray and Ready’s, and they give us work cards and bus tickets?’

‘Oh, sure, George, I remember that now.’ His hands went quickly into his side coat pockets. He said gently, ‘George…I ain’t got mine. I musta lost it.’ He looked down at the ground in despair.

‘You never had none, you crazy bastard. I got both of ‘em here. Think I’d let you carry your own work card?’

Lennie grinned with relief.

For Discussion:

1.) What dialogue craft skills work for you? Any tips to share?

2.) What authors do you like to read for dialogue?

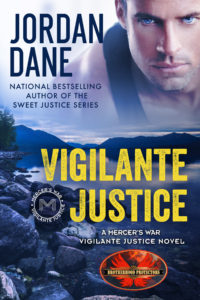

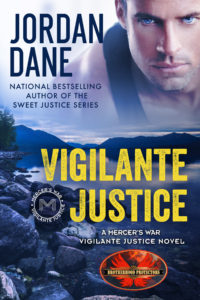

Vigilante Justice – $0.99 Ebook – Published by Amazon Kindle Worlds