I think every fiction writer, to a certain extent, is a schizophrenic and able to have two or three or five voices in his or her body. We seek, through our profession, to get those voices onto paper. — Ridley Pearson

By PJ Parrish

Picking a point of view is one of the most important choices a writer makes. Who are you going to trust to tell your story?

I’ll go out on a limb and say I think it is THE most important choice you make. Why? Because point of view — and how well you pull it off — is the most powerful way of developing that special bond between character and reader. And if you don’t create that bond, if you don’t make the reader invest emotionally in your characters, well, what you are putting there on paper is just a bunch of plot points.

So what’s your choice? A single narrator or do you need several? Should you go with first person, which provides immediate connection through the power of the “I” pronoun? Or do you chose third person, which gives you more latitude and depth, the freedom to paint on a larger canvas?

And if this isn’t enough to worry about, let me throw in a new wrinkle:

Intimate point of view.

In case you’ve been under a rock, intimate POV is all the rage in fiction right now, with editors gushing about it and pleading for it in their Track Changes. Which makes me want to dismiss outright as a fad. This, too, shall pass, like all the “girl” books gathering dust on the remainder table.

But the more I started thinking about it, the more I realized “intimate point of view” is really just another ratchet in our character development tool chest. Many of us are already doing this in our writing. And if you aren’t, well, maybe this is something you need to consider.

Now I have been trying to write this blog for two months. But this is slippery subject, and it’s hard to define. So if you read this and still go “huh?” the fault, dear reader, is probably mine. But I’m going to give it the old college try anyway.

One reason we chose first person is because it puts us right in the heart and mind of the protagonist. But with third person, without the anchor of the “I” pronoun, the intensity of that reader bond can be weak. I’ve read third-person novels that feel like I’m listening to an old transistor radio where the signal fades in and out and I can’t “hear” the protagonist’s feelings and thoughts clearly. When that signal wavers, I don’t bond strongly with the character and I lose interest in the story.

Why should you care about intimate POV? Because readers do. People read to have vicarious experiences. They want to walk the miles in your characters’ shoes, view the world as they do, feel their struggles, pains, triumphs and turmoils. The closer you the writer can connect with your characters, the greater the bond the reader will have with them.

So how do you do this? I think it helps to think of this as an extension of our oft-quoted writers axiom — Show Don’t Tell. In terms of POV, it becomes a matter of not merely describing feelings and thoughts but allowing the reader to enter the skins of your characters and experience everything just as they do. Third person intimate uses many of the best tricks of good first-person point of view. When you are in first person, every single thought and sensation is filtered through that one person. Which is one reason first person is easier to write and can feel more involving to the reader. But you can achieve the same bonding in third person if you are willing to dive deeper into intimate POV.

Okay, I tried to TELL you. Now let me SHOW you what I mean. Maybe this will help.

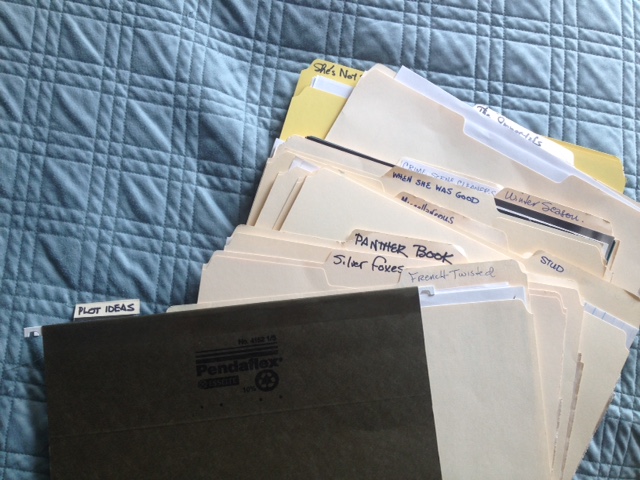

Bear with me but I am going to resort to using my own book here. I’m going to show you two versions, one a regular third-person POV and the second in a more intimate third-person POV. This is the opening of chapter 18 of my latest book She’s Not There. The set-up: This scene has my character Clay Buchanan at a moral crisis, what James calls a “man in the mirror” moment. (which I took literally, as you will see!) This is a huge turning point in the book and will set Buchanan on an irreversible dark path. I chose to put him alone in a quiet place so I could make his inner turmoil play in high relief by contrast. The first version is perfectly adequate and gets the job done. But in the second version, I am trying to immerse myself in this man’s soul.

CHAPTER 18 (adequate)

Buchanan stared at his reflection in the mirror and listened to the song playing on the jukebox. It was Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror.” How pathetic, he thought, to sit in a bar and stare at yourself in the mirror. But then he realized that maybe this was what he needed right now – a good long hard look at himself that might lead to a moment of moral clarity.

He finished his second scotch and set the empty glass down in the trough of the bar. His thoughts returned to the questions that had plagued him on the plane ride back from Georgia: What would happen if he had to stand trial for Rayna’s murder? What could he do with all that money from the deal he had struck with Owen McCall? And what exactly was he going to have to do to get that money?

Now here is the opening as I really wrote it:

CHAPTER 18 (intimate)

Was there anything more pathetic than staring at yourself in a bar mirror? But maybe that’s what he needed right now, a good long hard look at himself. Confront the man in the mirror, stare deep into his soul. Find a bright shining moment of moral clarity.

Buchanan picked up his glass. What was that Michael Jackson song? “The Man in the Mirror”? How did it go? Something about making a change?

He finished his second scotch and set the empty glass down in the trough of the bar. On the plane ride back from Georgia, he hadn’t had anything to drink. He had needed his head clear to think. Think about what might happen if he had to stand trial for Rayna’s murder. Think about the deal he had struck with Owen McCall. Think about what he could do with two million dollars. Think about what he was going to have to do to get it.

Note that I didn’t use one “thought” or “wondered” or “realized.” Note, too, that the sentences are often fragmented to mimic the fleeting rhythm of real thought. Humans under stress tend to not think “straight.” The writer’s trick is to get the feeling of this and still keep the reader on track.

Back to the adequate version now:

Buchanan looked down into his empty glass, thinking now about what a ruthless man Owen McCall was, and what it must be like to have so much power that you could buy anything — including a woman’s life. And he wondered if he could ever be like that, do whatever it took to get what he wanted.

He shut his eyes because, suddenly, there it was again. His dead wife’s voice was in his head, haunting him, and asking the question he was too afraid to ask himself: What do you want, Bucky?

I just want you to be quiet, he thought.

“Excuse me?”

Buchanan opened his eyes to see the bartender staring at him. He blinked her into focus. He didn’t even realize he had spoken.

“All I asked you was if you wanted a refill,” she said. “If you’re gonna get ugly, there’s the door.”

He held up his hands. “Sorry, I’m sorry. Yeah, bring me another, please.”

Okay, it’s not bad. But this is a man so tormented by his wife’s murder that he thinks she talks to him from the grave. I use this device throughout the book, as if Rayna is what is left of his moral compass, if he would only pay attention to it. By this point in the book every time the reader sees the italics and her nickname for him “Bucky,” they know it is Rayna talking to him in his imagination. Also, by now, Buchanan is starting to “understand” that even his wife is turning against him. Here is how I really wrote it:

Owen McCall’s face came back to him in that moment, how it had looked in the car, stone cold gray in the slant of the streetlight, how there was nothing coming from those hard blue eyes, like all the man’s energy was directed inward.

Maybe that’s what it took. Maybe you had to filter everything and everyone out and laser-focus everything you had back into yourself to become a man like that—a man who was successful enough to buy anything on earth. Including a woman’s life.

Could he do that? Could he be the kind of man who would do whatever it took to get what he wanted?

But what do you want, Bucky?

Buchanan shut his eyes.

Tell me, Bucky. What do you want?

“I just want you to be quiet,” he said.

“Excuse me?”

Buchanan opened his eyes to see the bartender staring at him. He blinked her into focus.

“All I asked you was if you wanted a refill,” she said. “If you’re gonna get ugly, there’s the door.”

He held up his hands. “Sorry, I’m sorry. Yeah, bring me another, please.”

Another place intimate point of view can be really effective is when you have to enter a flashback. In this chapter 18, I realized I had to finally explain to the reader how Buchanan’s wife Rayna had been murdered. When you have to inject a flashback, as we all know, you want to get in and out as fast as you can. Flashbacks work best during what I call “quiet moments,” when your character is taking a break from the action and can “remember” and thus narrate for the reader what has happened in the past. Here is the adequate version of my Rayna flashback later in the same Chapter 18:

The bar had gone quiet and his thoughts moved in to fill the void. Usually, when he thought about what had happened ten years ago, his memories were fuzzy. But now, for some reason, everything was coming back to him with a painful clarity.

He remembered how hot it had been that September day, and how annoyed he felt because the baby’s asthma was bad, making him cry so much that Buchanan could barely hear the football game on TV. And his daughter Gillian had made such a mess on the rug with her toys. Rayna had come in the kitchen, grabbed the remote and muted the TV, demanding to know why he hadn’t answered the ringing phone.

He had ignored her, because he was angry about so many things. Angry because the AC was broke and they had no money to get it fixed, pay the mortgage or even cover the baby’s medical bills. He was angry, too, because he hated working as an insurance adjuster and if Rayna hadn’t gotten pregnant, he would have been able to finish his psychology degree. When he finally did look up at his wife, he realized she saw him exactly as he saw himself — made small and mean by his disappointment.

Here’s how I really wrote it:

He watched two guys finish their ping-pong game. The roar in his head had quieted. Even her voice was gone, for the moment at least. He knew this was dangerous, letting his mind go empty, because that’s when the memories slid in. And they were coming now, not like they usually did, like he was seeing them through a soapy shower curtain, but with a sharp, stabbing, awful clarity.

It had been hot that September day, with tornado warnings crawling across the bottom of the TV screen as he watched the Titans game. The baby was crying in the kitchen, making that awful wheezing sound he made when his asthma was bad, and Gillian had made a mess on the rug with her Shrinky Dinks. Rayna had come into the living room and grabbed the remote, muting the TV.

Bucky, didn’t you hear the phone?

No. Did it ring?

He hadn’t even looked at her. The AC was on the fritz, he was hot and miserable, thinking that this was his first day off in two weeks and all he wanted was to be out in the woods with his binoculars and birds. He was thinking about the late mortgage payment and the baby’s unpaid medical bills, thinking about his peckerwood boss and how much he hated working as an insurance fraud investigator. Thinking that if Rayna hadn’t gotten pregnant again, the money they had saved might have been enough for him to go back to night school and finish his psychology degree.

When he finally looked up at his wife, he saw something there in her clear blue eyes he didn’t want to see—himself, made small and mean, because this was never what he had envisioned for himself, and it was too late to go back and fix it.

Again, note the fragments and details — that’s how our brain stores its memories, in flashes of images, sights, sounds and smells. Also, by being in intimate POV, I try to establish some sympathy for Buchanan so the reader can maybe begin to understand his anger. This flashback goes on from here, and I kept it as short as I could but still gave the reader enough background so they could understand the depth of Buchanan’s torment. (He was brought up on charges for her murder but was cleared. Her body, and that of his infant son, were never found.)

Okay, enough about me. Let’s talk about you. And what you can do to make your character’s point of view feel more intimate. Here are some things to watch for:

Know your character inside and out: Intimate POV allows your story and scenes to be experienced from the inside out rather than “reported” from the outside looking in. But this is really hard writing. To pull this off, you must know your character intimately. Everything –- every word, the syntax, the accent, the idioms – must arise from the character’s background and experience. Unless you know your character’s inner most feelings, thoughts and motivation, you won’t be convincing. And you must be able to answer, at the deepest levels, WHAT THE CHARACTER WANTS.

Remember the movie Ghost? Whoopi Goldberg plays a medium who claims that spirits enter her body and talk to their loved ones. Of course, she’s a charlatan, until Patrick Swayze shows up and dead people really do start talking to her. There’s a great scene where the impatient ghost Orlando jumps into Oda-May’s body and takes over. This is what your characters must be free to do — jump into your consciousness and inhabit it so intimately that you and they become one. As Ridley Pearson puts it, you must be able to have two, three, five voices in your body. But when you the writer “speak” on paper, we should hear your characters, not you pretending to be them.

Cut out filter words. Filter words or phrases are you the writer relating things and action rather than letting the reader experience things “first hand” through the character’s sensibilities. You don’t need to remind readers that a character is “feeling,” “hearing,” “seeing” or “smelling.” Delete these words whenever possible. But while paring down, look for ways to inject something personal and telling about your character. Examples:

Adequate: He smelled the rotting dead body lying in the flower bed. Better: First came the sweet scent of roses, but as the wind shifted, the chemical cocktail of rotting flesh made him stop in his tracks. It was funny what you learned after fifteen years in homicide. Dead animals smelled different than dead men.

Adequate: Mary heard the screen door slam and felt the breeze ruffle her dress. Better: The screen door slammed. Mary’s dress waved. (stealing from Springsteen there!)

Limit Your Dialogue Tags. Dialogue tags are the words you use when describing the speaking character (e.g. she said, he shouted, he whispered, etc.). Get rid of as many of these as you can, without sacrificing clarity. Intimate POV works best when your character is alone, but when he’s not you must be careful to let the reader know who’s talking. If you are worried about clarity in thinking, shame on you — it means you are head-hopping in your POV.

Know when to stop: Not every scene needs to be written from an intimate POV. Often, you are just moving characters around in time and space and we don’t need to feel every single emotion they do. The intimate sensibility should always be there but sometimes it just hums along in the background as the action unfolds. Which makes it all the more powerful when you do pull out the stops and let Orlando jump into your body.

___________________________________________________

Blatant promotional postscript: I just found out Thomas & Mercer is offering She’s Not There in a month-long special promotion for $1.99. It runs through August. https://www.amazon.com/Shes-Not-There-P-J-Parrish-ebook/dp/B00U0N5GDI#navbar. We return you now to our regular programming…