A lot of writers, especially crime writers, have an image that we think we’re trying to keep up with. You’ve got to be seen as dark and slightly dangerous. But I’ve realized that I don’t need to put that on. People will buy the books whether they see a photo of you dressed in black or not. — Ian Rankin

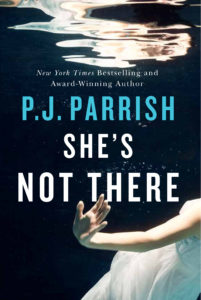

By PJ Parrish

I wish I had read that quote from Ian Rankin before I had my first author photograph done. It would have saved me a lot of embarrassment and the phone call I got from an old friend who I hadn’t seen in a couple years (call paraphrased here due to aging memory cells):

Him: “Are you…okay?”

Me: “Okay? What are you talking about?”

Him: “I saw your book in Barnes and Noble.”

Me: “Did you buy a copy? Tell me you bought a copy.”

Him: “I did. But it made me worried about you.”

Me: “Good lord, it’s not that bad, is it?”

Him: “I haven’t read it yet.”

Me: “But you’re worried…”

Him: “Yeah. You look so, so…angry.”

Me: “Angry? Why would I be angry? I finally got published!”

Him: “Or maybe you’re sad. I can’t really tell. What are you so depressed about? Did you get a divorce? I can give you the name of my shrink.”

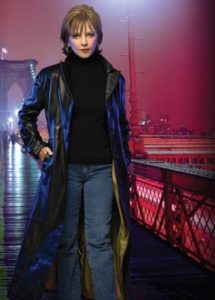

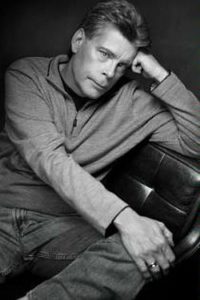

That’s when it hit me. My friend had seen my author photograph on the back of my book. I knew the picture was bad. I knew it the moment the photographer sent back the contact sheet with all those mini-me’s scowling out at the world. But I was in denial and he was a pro who had taken many author photos, so I chose one and ordered the prints anyway. But I’ll let you be the judge. Here’s the photo:

It’s okay. You can say it. I look awful. I got my hair and makeup done, yes. And I wore my black leather jacket and my best frown because I was a woman writer in the hard-boiled world where the men who came before me and those who now crowded around me smoked Camels, drank scotch and wrote things like, “I won’t play the sap for you, angel.”

I wanted to look serious. I ended up looking mean.

I’m not mean. Or sad or angry. Below left is my very first author, from 1984, way back when I was writing romance and family sagas.  Who would you rather buy a book from? That hopeful wry writer in white at left or that crabby miscreant in black above? What happened to me?

Who would you rather buy a book from? That hopeful wry writer in white at left or that crabby miscreant in black above? What happened to me?

I’ll tell you what happened. I really thought, when I switched genres, I needed to look tough and distant, like I could chew glass. I didn’t realize that what I really needed to do was just be myself. Which is actually what I was doing when my photographer and I went out for beer and pizza at John’s in the Village and he captured this candid moment that became my official author photo.

What can you learn from my experience? Lots, I hope. Because whether you are published or still trying to get there, this isn’t just about getting a good author photograph. It’s a lesson in being true to yourself.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, an author photo is worth oh, maybe a million? Readers buy books for myriad reasons. They heard from a friend that the book was good. They read the reviews on Amazon or Good Reads. A clerk in a bookstore recommended it. Or very often, they picked up the book, read the blurb, maybe the first page. And maybe they looked at the picture of the person who wrote the book. Now I’m not suggesting that the wrong author photo can make or break a sale. I’m with Ian Rankin on this one, believing that if you continually produce good stories, looks don’t matter. But in this competitive market place, it’s not a bad idea to get a good author photo. Here’s why:

- You’ll need one for publicity purposes. Unless you’re a star at a large publishing house, you probably won’t get the photo done for you. But you will be expected to provide one for publicity and promotion. If you are self-publishing, you must have a website and that means you must have a good photo of yourself on it.

- It engages the reader in a sub-conscious way. The right photo can send a positive signal to a potential reader. First, that you are a professional. Second, that you are approachable i.e. the Consciousness behind the characters they will be spending the next couple weeks or months with.

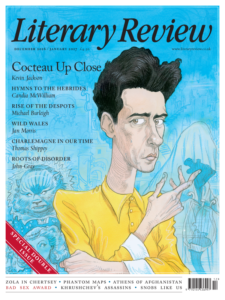

- It establishes you as a recognizable “product.” I know this idea is repugnant to some folks, but the most successful authors make themselves sell-able with a consistent image. Think Mr. Peanut or Colonel Sanders. Think of this guy:

- It conveys the tone of your work. This is important. We have talked often here at TKZ of the importance of tone consistency in your work. Many elements — cover art, type-faces, and of course the writing style itself — help readers grasp what kind of writer you are. Are you writing YA or adult? Are you hard-boiled or lighthearted? All of this needs to show in your own face in that author photo. But don’t make the mistake I did and put on a leather coat and a sneer, thinking that will help. It’s more subtle than that.

Here are some examples of conveying the right tone in author photos. Chris Grabenstein started out writing his adult Ceepak mysteries loosely set around a carnival theme but branched out to a children’s series. Below are his two author pics. Guess which one goes with which series:

And then there’s Nora Roberts aka J.D. Robb. Nora has written more than 200 romances. But when she puts on her thriller cloak as J.D. Robb, she has a different look. Same woman, yes, with a definite brand. But with a subtle difference in the photos that appear on the back on her books:

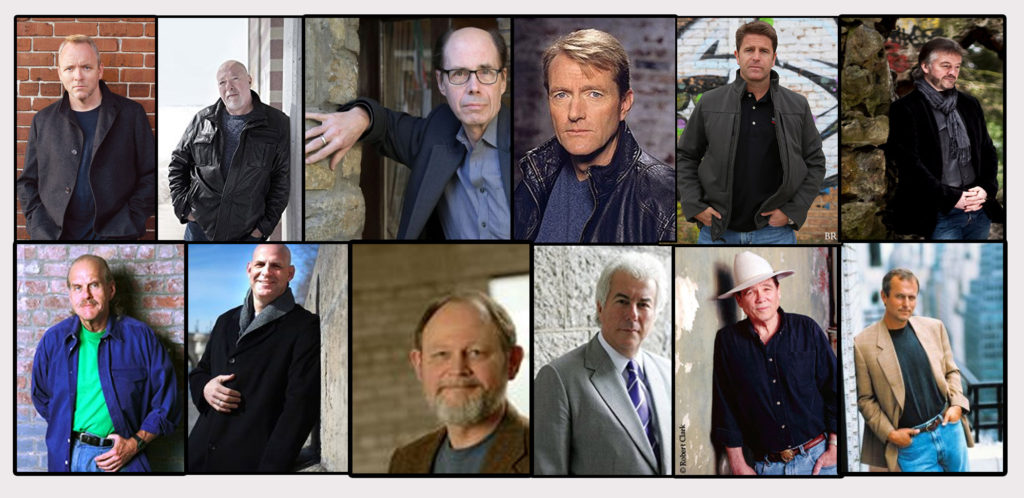

I think it might be easier for guys in crime fiction to come up with a good pic. They just have to slap on a shirt, maybe a blazer and good jeans and lean up against a brick wall. (See below).

Women who write hard-boiled or more serious crime fiction have it a little harder, what with the make-up, hair, and the expectations of the genre. Where is the sweet spot for us between serious and…mean? I think these two found it:

Regardless of gender or sub-genre, getting the right photo isn’t easy, and there are plenty of bad ones out there, even when they are done by professionals guided by publishing house promotion staffs. My favorite blogger, Chuck Wendig, just ran his Awkward Author Photo contest Click here to go see the entries and the winner, but don’t get any bright ideas, okay?

Regardless of gender or sub-genre, getting the right photo isn’t easy, and there are plenty of bad ones out there, even when they are done by professionals guided by publishing house promotion staffs. My favorite blogger, Chuck Wendig, just ran his Awkward Author Photo contest Click here to go see the entries and the winner, but don’t get any bright ideas, okay?

There are also some pretty bad author photo cliches:

- Hand under the chin, at side of forehead or anywhere in vicinity of face. It worked for Oscar Wilde but now looks silly.

- Manual typewriter in the picture. Who are you kidding?

- Big shaggy dog to soften image or distract from author.

- Soft focus. You really want to look all Vasolined like Doris Day?

- Cigarettes. I think Ian Fleming was the last guy to pull this one off successfully but that didn’t stop photographer Szilvia Molnar from getting a great Twitter feed off the subject “The Man, The Writer, and his Cigarette.”

- The vacant stare into space. Jack Kerouac did this a lot but maybe he was writing this line in his head: “I had nothing to offer anybody except my own confusion.”

Given my bad experience with author photos, I am probably the last person who should be giving you advice on what to do with your own. But I am going to give it a try, based on some research I did and some tips I got from some author friends. First off, there’s the big question: Hire a pro or do-it-yourself?

Hire a professional, if you can. Yeah, it can get expensive. And you don’t always get what you pay for (see my experience above). But you will get a basic level of quality and selection that you won’t get doing it yourself or having your brother take a pic of you with his iPhone. Ask fellow authors for recommendations. I ended up getting a photo done by my late great friend Barbara Parker, who when she wasn’t writing mysteries was a professional photog.

Take your own pic. Yes, it can be done but it’s a giant pain, and there’s a good chance the results will look amateurish. But if it’s all you can afford at first, so be it. Click here for some good tips I found on line.

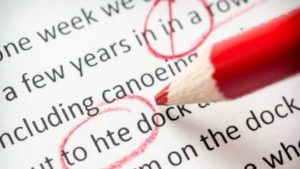

Get both black and white and color versions. Or make sure the quality is good enough that you can convert color to gray tone prints. VITAL: The original must be high-resolution. Let’s say you get a gig at a library and they need your mug. If that little image you put on your website can’t be downloaded and blown up for a flyer or poster, you’ve lost out. And if you ever meet my sister Kelly in a bar at a writer’s conference, don’t get her started on the topic of author photos. She does a lot of program books for conferences and has been sent blurry snapshots, high school portraits, and family group shots wherein she has to figure out which one is the writer. One guy just told her to photoshop out the family dog he was holding. This is how the guy appeared in the program book:

Portrait or environment? You can do a simple head and shoulders photo. But you might want to consider a second photo of you in some kind of environment that matches the tone or content of your book(s). And that don’t-do I mentioned about dogs? Well, if you write a series about a dog or maybe a cozy series that suggests a softer tone, including your pet can work for you, make you look accessible to your readers.

Here are two photos of my friend Reed Farrel Coleman. One is a portrait but the second reflects the New York setting of his books.

If you can’t afford a stylist, take along a friend who has a good eye. I am getting ready to put my condo on the market and I hired a professional photographer to come take photos for Zillow, Realtor.com and the MLS listing. He was amazing, right down to repositioning electrical cords and hiding my bath mats. Don’t do less for your own face. You don’t want a plastic plant growing out of your head, your tie askew or lipstick on your teeth. A good photographer should be helpful here but don’t count on it.

Be careful what you wear. Stay away from prints and fussy clothes. Keep your look simple so readers notice your face, not your fashion choices. I don’t care that Dan Brown has sold a zillion books. Someone should have told him dad jeans are ugly.

Don’t over-photoshop. Yes, you can retouch some because even if you look like her, you don’t want to come off like Norma Desmond. But you’re not a super-model so don’t over-do it with erasing wrinkles and taking out that double-chin. You’re trying to sell books not link up on Match.com.

Don’t wear weird jewelry or any variation on lingerie. When Anne Rice was starting out, she was often photographed looking like a cross between Stevie Nicks and Morticia. Now she has this elegant-mystery vibe going in her pics, with black tops, one great necklace, and a smart bob. And even if you write romance, keep the pink and pearls under control until you have published 722 novels like the woman pictured below did. Then, like George R.R. Martin, you can wear whatever you want.

Consider getting a third horizontal format photograph that includes some negative space. Position yourself to one side and leave the rest blank. This negative space can then be used by you or a designer in your website header. You can insert type easily into the photograph. I love this photo below of Walter Mosley, not just because it conveys his personality but also for its negative space. And yes, he’s staring off into space but I don’t care.

And speaking of personality…how much is good and how much is over the top? It depends on you as an author, how good your photographer is, what kind of books you write, and what mood you want to present to the world. Sometimes, going against what is expected can work wonders. When Kareem Abdul Jabbar began writing books, he didn’t do the standard author head and shoulders VERTICAL shot. Look at this gorgeous horizontal photograph. Look at those hands.

Speaking of hands, I love this photograph below by romance writer Maya Rodale. It’s glamorous and sexy, probably like her books. But notice those wire rim glasses she’s holding…what a nice touch!

And then there is this author photo…

That’s YA author Maggie Steifvater who has some stunning photos on her website. Click here to see more. But oddly, she doesn’t have one photo of herself that you can download, so if someone needs a publicity picture, they have to hit the internet and search for one. Rule No. 2 about author photos: Never make someone who is selling your book work harder than they have to.

That’s YA author Maggie Steifvater who has some stunning photos on her website. Click here to see more. But oddly, she doesn’t have one photo of herself that you can download, so if someone needs a publicity picture, they have to hit the internet and search for one. Rule No. 2 about author photos: Never make someone who is selling your book work harder than they have to.

So, that’s it. I know, I know…you don’t want to think about this. You have too much on your author plate already and you don’t like having your picture taken anyway. Well, it goes with the turf. You don’t have to get a Annie Liebovitz-quality portrait when you’re just starting out. Just get a good, clear, high-resolution head shot that tells the reader what kind of person you are and what kind of books you write. The rest is gravy.

I will leave you with two final images that should give you hope.

If this guy’s author photo went from this:

To this…

Well, maybe yours can, too.

_________________________________________

P.S. Chuck Wendig just posted the winners of his bad author photo contest. Click here to see them but don’t have a mouthful of coffee when you do.