Learn the rules like a pro so you can break them like an artist. — Picasso

By PJ Parrish

So I cracked open a new thriller the other day. Starting a new read is like going on vacation. You buy your ticket and you’re filled with excitement and expectations. Where am I going to go? What cool sights will I see? What fascinating people will I meet? What great adventures await me?

I had heard this book was really good, and I haven’t been swept away by a novel in a long time. I was ripe for seduction.

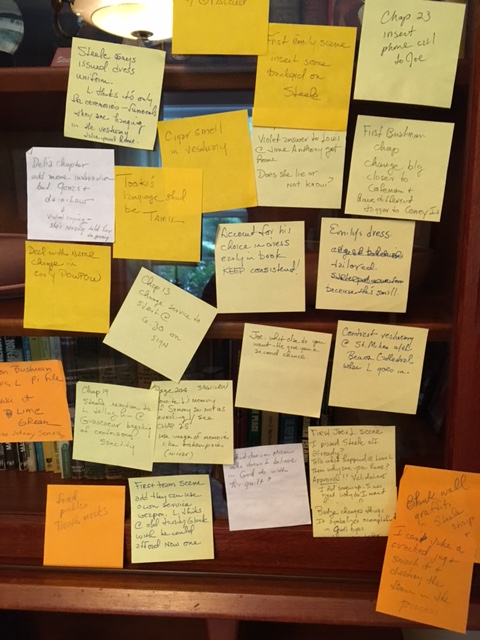

Then I started reading it. And the writer in me took over the reader in me. I started to analyze what the author was doing. Good grief…he broke every rule we here at TKZ talk about:

- The opening graph was slow and boring.

- The style mixed past and present tense

- The writer cut away at a crucial peak moment in the set-up action scene and didn’t show it “on camera.”

- The first four chapters are heavy with backstory info dumps

- The point of view head-hops between characters in mid-scenes

- One chapter ends with “little did he know that…” (death was coming for him)

But I couldn’t put the book down. See all those bullet points above? I didn’t care about any of them because the story was so darn compelling that the writer in me was elbowed aside by the reader in me. I’m now about halfway through the book and it’s getting better and better. I’m totally invested in the characters, even the detestable ones. I can’t foresee what is going to happen. And I can’t wait to see how this all plays out.

I guess you want to know the title. It’s Before the Fall by Noah Hawley. It won the Edgar for Best Novel this year.

Now Hawley isn’t exactly a novice. He’s written four novels before this, including two that could be classified as thrillers. He’s also a screenwriter, best known for creating and writing the television series Fargo and Legion.

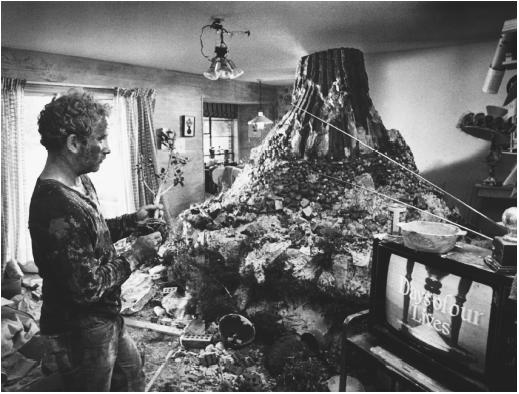

Before the Fall definitely has the bones of a good screenplay. Here’s the setup: A privileged family sets off on foggy night from Martha’s Vineyard with a down-on-his-luck painter tagging along for a ride back to Manhattan. The plane goes down into the ocean and only two survive — the painter and the family’s four-year-old boy.

The story then moves into flashback, with detailed dossier chapters on the main characters, and the driving ideas and themes start emerging — the harsh price of our 24-7 media culture, the twists fate takes, how ordinary people become heroes, and the inextricable ties that bind us together.

Let’s go back for a moment and the rules that Hawley broke. Here’s the opening paragraph:

The private plane sits on a runway in Martha’s Vineyard, forward stairs deployed. It is a nine-seat Osprey 700SL, built in 2001 in Wichita, Kansas. Whose plane it is is hard to say with real certainty. The ownership of record is a Dutch holding company with a Cayman Island mailing address, but the logo on the fuselage say GULLWING AIR. The pilot, James Melody, is British. Charlie Busch, the first officer, is from Odessa, Texas. The flight attendant, Emma Lightner, was born in Mannheim, Germany, to an American air force lieutenant and his teenager wife. They moved to San Diego when she was nine.

Snooze-fest, right? I mean, none of these people is important. They all die within sixteen minutes of takeoff. Who cares where the plane was built? If this showed up on one of our First Page Critiques we’d tear it to shreds. Here’s the second paragraph:

Everyone has their path. The choices they’ve made. How any two people end up in the same place at the same time is a mystery. You get on an elevator with a dozen strangers. You ride a bus, wait in line for the bathroom. It happens every day. To try to predict the places we’ll go and the people we’ll meet would be pointless.

Again, this breaks the usual thriller rules. It is omniscient point of view, the writer telling us something about the book’s theme. It’s a tad portentious. The protagonist artist won’t even come on scene for another nine pages and even then he’s a blip on the narrative radar. Yet I was very willing to let the writer rather than the characters steer the story at this point.

The plane takes off. At the end of what is essentially a prologue (untitled as such) we drift into the wife’s POV:

As she does at a thousand random moments of every day, Maggie feels a swell of motherly love, ballooning and desperate. They are her life, these children. Her identity. She reaches once more to readjust her son’s blanket, and as she does there is that moment of weightlessness as the plane’s wheels leave the ground. This act of impossible hope, this routine of suspension of the physical laws that hold men down, inspires and terrifies her. Flying. They are flying.

Then here is the last sentence of the “prologue”:

And as they rise up through the foggy white, talking and laughing, serenaded by the songs of 1950s crooners and the white noise of the long at bat, none of them has any idea that sixteen minutes from now their plane will crash into the sea.

Little did they know…

Maybe Hawley deserve a small wrist slap for that one, but I was willing to let him get away with it. It fit in with the tone he was using, like he had gathered us all around a campfire and was pulling us in. We know from the back copy what is going to happen, so he’s not stepping on any surprise here.

Back to the broken rules. In the next chapter, Hawley switches from present tense to a more conventional past tense. And it is all backstory on the artist, Scott Burroughs, starting with a key childhood memory of Scott going on a family vacation to San Francisco that culminates in the boy watching Jack LaLanne swimming from Alcatraz pulling a boat in his wake. The chapter is laden with details and ends with the author telling us that as soon as Scott got home, he signed up for swimming classes. We are left to understand that this memory chapter is here to underscore the theme of heroism and doing the impossible. But we really want to return to that plane crash, right?

Here is the opening of chapter 2:

He surfaces, shouting. It is night. The salt water burns his eyes. Heat singes his lungs. There is no moon, just a diffusion of moonlight through the burly fog, wave caps churning midnight blue in front of him. Around him eerie orange flames lick the froth.

The water is on fire, he thinks, kicking away instinctively.

And then, after a moment of shock and disorientation:

The plane has crashed.

Why didn’t Hawley show us the crash “on camera?” He’s a screenwriter! We should have seen the whole crash, like that terrifying scene with Tom Hanks in the film Castaway? Yet Hawley CHOSE to withhold it. As a reader, I initially felt deprived of a visceral experience. But when I got to a later chapter, I understood why he did it. When Scott the artist is finally safe and has to recount the crash for authorities, the horror of the crash feels even more vivid and it becomes a tool for Hawley to comment on the fragility and unreliability of memory.

The chapter is all action (again in present tense) that intensifies when Scott happens upon the little boy clinging to a cushion. Scott, dislocated shoulder and desperate, takes the child on his back and starts swimming for a shore he can only see in his hopes. The chapter after takes place in the hospital and starts dealing with the media frenzy and Scott’s realization that he is man who has been hiding from a failed life and now has been pushed into the light.

The next chapter is titled DAVID BATEMAN, April 2, 1959 — August 23, 2015. This reverts to past tense and is devotes to the backstory of the dead father, who is a younger, handsomer version of Roger Ailes in that he created a Fox News type network.

The rest of the book jumps back and forth between present (Scott and the boy) and the past (backstories on all the key dead characters). Again, the rule is broken: Stay with the linear more visceral plot. But I wanted to know, needed to know, what had brought the dead characters to their tragic ends. There is reason the book is called Before The Fall. Yes, it can be a biblical allusion, that people are innocent until they are corrupted. But it is also a comment on the novel’s structure and the choice Hawley made: What happened BEFORE is just as important as what happened after.

I didn’t realize until I went back and looked at the notes I had made in the margins that Hawley broke another basic rule. He has no chapter numbers. Most chapters are titled: “Storm Clouds,” “Orphans” “Funhouse” and such. But the titles are not what they seem; they all have double meanings.

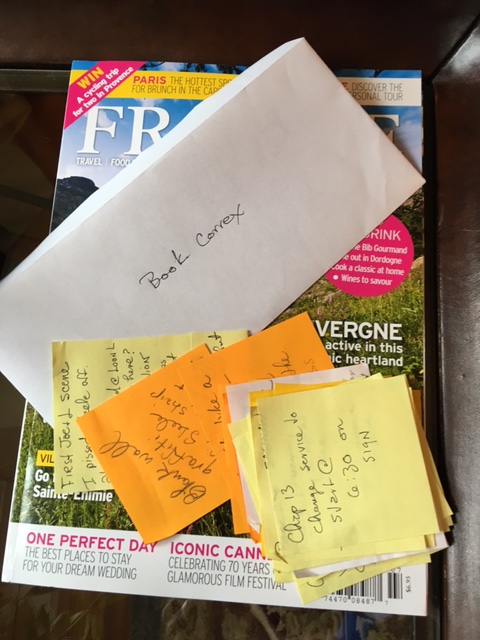

I wish I had finished the book so I could comment more fully on it here for you. But as I said, I am halfway through and it is keeping me turning the pages and the characters are very alive in my mind when I put the book down. So yes, you can break the rules. In fact, sometimes you must. I will probably go back and read Hawley’s other novels now, because I am interested not only in what the author has to say but how he says it.

But for now, I’m off on an adventure. I’ll let you know how it turns out when I get back.