“I believe more in the scissors than I do in the pencil.” – Truman Capote

By PJ Parrish

I hate Lee Child.

Well, at least I got your attention.

Okay, I don’t really hate the guy. He’s actually one of the menschiest men in our business. But about once a year, right around the same time, I really really really hate the guy.

Why? He claims he never rewrites. He says he writes one draft and that is what makes it into print. Here is an excerpt from an interview he gave to a reporter for the Independent newspaper in Britain:

“This isn’t the first draft, you know.”

He’d only written two words. CHAPTER ONE.

“Oh,” I said. “What is it then?”

“It’s the only draft!”

Right then, he sounded more like Jack Reacher than Lee Child. More Reacher than writer.

“I don’t want to improve it. When I’ve written something, that is the way it has to stay. It’s like one of those old photos you come across. From the 1970s. And you have this terrible Seventies haircut and giant lapels on your jacket. It’s ridiculous – but it’s there. It is what it is. Leave it alone.”

Okay, let me try to qualify this a little. This week I am starting rewrites on our latest Louis Kincaid thriller. Now, we’re pretty clean writers. We write so slowly that things tend to fall in place as we go along. But this newest book was different. It didn’t chug nicely along, with a little lurch or two along the way. This one was a big Victorian locomotive that would speed ahead for three chapters, hit a hill, careen backwards, smack into a tree and then start groaning forward again, all the while belching out noxious clouds of purple smoke.

But at least it is done. And while we normally now would be going in with a light heart and an Allen wrench to fine-tune, this time we are going back into the manuscript with grim determination and a scalpel in one hand and sledgehammer in the other.

I know the story is solid. In fact, it might be the best book we’ve written. But I also know we have weeks of rewrite hell ahead. How did this happen? Partly because this book came when both Kelly and I had a lot of life stuff going on. For my part, I moved to a new city after living in the same place for 40 years, so I often had to break my vow of writing daily and thus I had to leave my imaginary world and live in the real world of closing statements and cardboard boxes. The main man in my life wasn’t my hero Louis Kincaid but Two Men and a Truck.

Writing tip of the day no. 1: Even when life intrudes, do everything you can to maintain daily contact with your novel. Visit your imaginary world every day, even if it’s just to go back and read what you already wrote.

But that wasn’t the only problem. The story we chose this time was very ambitious, both in plot, characterization and theme. This time out, for book no. 14, we weren’t just juggling with fire torches, we were juggling with chainsaws. And at times, we lost our way in both the arcs of the case (plot) and its people (character).

Writing tip of the day no. 2: Even if you’re a pantser like me, create a road map for your story. You don’t have to stick to the outline or template, but when you get distracted, it can be a path back to the main story road.

Sometimes, learning about how other writers do things – watching how someone else makes their sausage – can help you find your own process. So let me share some things I’m facing as I go into rewrites this week. It won’t be your tao, but it might spark a how.

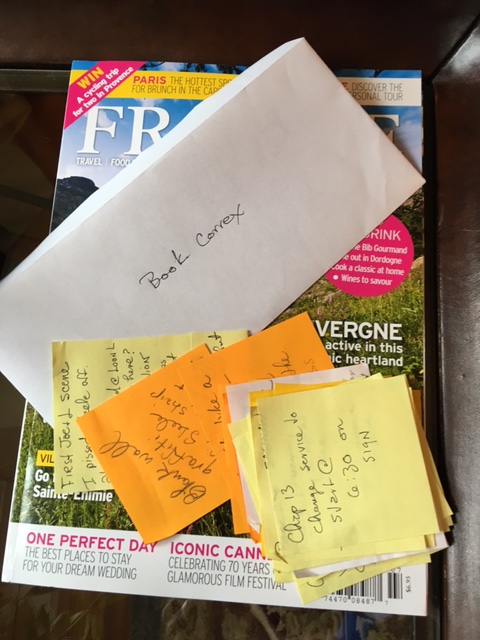

First, we have to deal with the little stuff. Things like changing a character name or setting up the bread crumb trail of your clues better. Kelly and I deal with these small potatoes by creating Post-It notes. Here’s a typical Skype conversation for us:

Kelly: We need to beef up the FBI dossier on Steele that Emily gives Louis.

Me: Where do you think it should go?

Kelly: How about in the first restaurant scene where they first talk about the team?

Me: Good idea.

Kelly: Make a sticky note or you’ll forget it.

So I scribble out a note on a Post-It and slap it up on a board in my office. But as I packed up my office, I had to stuff all the “sticky notes” in an envelope .

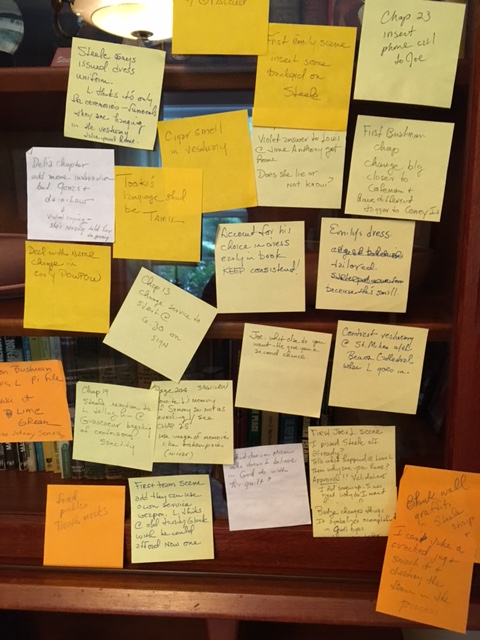

Today, I got them out of the box and spread them on the glass door of my desk so at least now I can see what awaits me.

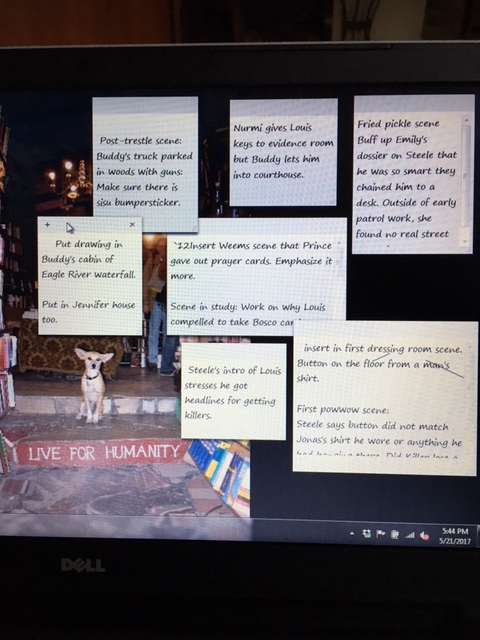

This is only part of them. I ran out of room. It gets worse. While we were in mid-move, we were still trying to work so I had to resort to making Microsoft sticky notes that I slapped onto my desk top:

Now do you understand why I hate Lee Child?

What’s weird about this is that normally I love rewriting. At this point for me, the grunt work is done, the sweat has dried, and I am merely redecorating, pulling weeds, repainting, and repositioning the furniture. But this book needs a new entry door, a couple walls knocked down, a massive new support beam around chapter 25, and a new addition built onto the back. It’s not Property Brothers; it’s This Old House.

Writing tip of the day no. 3: Sometimes you don’t see the real problems until you have finished the whole book.

It wasn’t until we got around page 400 that Kelly and I realized just how much big structural work was ahead of us. We couldn’t see these issues until we had traveled the entire course of the story. We had been in the PLOT trees for so long that it wasn’t until we emerged back out into the open that we could look back and clearly see the CHARACTER/THEME forest.

So what do we need to fix? Here’s just a few things:

Chapter 1: Yeah, I hear your groans. Because if you read our First Page Critiques here, you know how important the opening moments of your story are. Our story starts slowly, with Louis returning to his home state of Michigan to take a job with a new prestigious cold case squad led by the police captain who, eight years before (in book 2), had caused Louis to lose his job. Okay, that’s a good obstacle for Louis but it’s not a sexy opening for a thriller. So we wrote a “prologue” in which two young boys are running for their lives from an unknown person who wants to seal them in a box. Well, THAT’S attention-grabbing. But as we neared the end of the book, we realized the scene felt artificial, like we were desperate to inject action into the opening. We were trying to gin up the story, but the scene was not organic to what came after — Louis on the first day of the job.

So we’ve axed the boys scene and are writing a scene between Louis and his new boss that will play on the tension between the men and stress the high stakes for Louis.

Writing tip of the day no. 4: Don’t be afraid of the slow opening as long as it has tension, hints at a major conflict, or conveys that something has been disturbed. You don’t have to throw a boulder into a lake to make waves; sometimes a well-aimed rock creates ripples enough to make the reader want more.

Another thing we need to fix is our characters’s motivations. Okay, I’ve been married for 35 years and just when I think I know my husband, he does something that makes me think, blink or just laugh my ass off. So it should be with your characters. You won’t know everything about them when you start, so don’t expect to. Keep control of them, yes, but be open to their surprises and their growth. Kelly and I found we didn’t know really know what drove our villain until he was vanquished around page 350. Now we have to go back and build up his early scenes — putting in that crucial beam or two! — so his final actions make sense. Even the bad guys deserve this respect.

Then there’s the last thing we need to fix — our theme. This one is maybe the hardest because theme is a slippery thing. I think theme is really important to good books. It is what your book is really about at its heart. It isn’t plot. Here’s Stephen King on the subject:

Writing and literature classes can be annoyingly preoccupied by (and pretentious about) theme, approaching it as the most sacred of sacred cows, but (don’t be shocked) it’s really no big deal. If you write a novel, spend weeks and then months catching it word by word, you owe it both to the book and to yourself to lean back (or take a long walk) when you’ve finished and ask yourself why you bothered–why you spent all that time, why it seemed so important. In other words, what’s it all about, Alfie?

When you write a book, you spend day after day scanning and identifying the trees. When you’re done, you have to step back and look at the forest. Not every book has to be loaded with symbolism, irony, or musical language (they call it prose for a reason, y’know), but it seems to me that every book–at least every one worth reading–is about something. Your job during or just after the first draft is to decide something or somethings yours is about. Your job in the second draft–one of them, anyway–is to make that something even more clear. This may necessitate some big changes and revisions. The benefits to you and your reader will be clearer focus and a more unified story. It hardly ever fails

We weren’t sure what this book was about, to be honest. It is about the murder of a mega-church minister — and how that murder ties into the little boys who were nailed into a box and left to die. But that’s just plot. What does all this mean? We knew the theme was loosely about religion. But It wasn’t until Kelly wrote one line of dialogue in chapter 34 that we found the theme. The line came from an atheist whom Louis interviews:

What does a man do with his guilt if he doesn’t believe in God?

That line made us realize our book’s heart was about how people who are damaged — and people who inflict damage on others — still find a reason to believe in something. But now we have to go back and carefully calibrate each character, through their actions, thoughts and words, to reflect that main idea. And yes, there is an answer even for the villain.

So, if you’ll excuse me I have some heavy lifting to do. If you are about to finish your book — huzzah, huzzah! — let me leave you with a couple miscellaneous bullet points about surviving rewrite hell.

Don’t get caught in ego-trap that your first draft is great. Hemingway himself said the first draft is always crap. (well, he used a different word).

Sometimes to fix it, you have to break it.

Let your first draft bake. I call this the de-cheesing time. Finish the book, let it sit for at least two weeks, then print it out and read it. The bad parts will stink like bad Brie.

Be courageous but careful. Rewriting is like eating an elephant. It’s one bite at a time.

Take out all the dumb words. Figure out what your writer tic is — mine is an overuse of “then” and “suddenly.” Excise all the flabby physical movements like, “He nodded his head.” (He just nodded.) Don’t keep repeating physical attributes. Once you tell me the lady has sea foam green eyes, don’t tell me again.

Hire an editor if you need one. And most of us need one badly. There is nothing more valuable than a trained reader who will tell you the truth and whose only interest is the quality of your book.

Sometimes you have to add, not subtract. Contrary to what Truman Capote, not every rewrite needs scissors. Sometimes you need to put more meat on the plot bones or inject blood into anemic characters. Stop obsessing about word count. The book will be as long as it needs to be.

Have a plan going in. After you’ve let the draft bake and given it a fresh read, write down the things — big and small — that you have to deal with. Here’s Chuck Wendig on the subject in his usual colorful style:

You write your first draft however you want. Outline, no outline, finger-painted on the back of a Waffle House placemat in your own feces, I don’t care. But you go to attack a rewrite without a plan in mind, you might as well be a chimpanzee humping a football helmet. How do you know what to fix if you haven’t identified what’s broken? This isn’t the time for intuition. Have notes. Put a plan in place. Surgical strike.

And as you eat the elephant, keep an eye out for that theme. Or as Dorothy Parker put it in her book on writing:

I would write a book at least three times–once to understand it, the second time to improve the prose, and a third to compel it to say what it still must say.

But, after all this, after all this advice I’ve set out here, isn’t it fair to let the King of the Perfect Draft have the last word? Take it, Lee Child…

My honest answer is ignore advice because it’s got to be your product. It’s got to be an organic product with a vital, vivid integrity of its own and you’ll never get that if you’re worried about what other people are telling you to do.

Morning, PJ, and thanks for another thoughtful post. Your blogs are short courses on difficult subjects. Rewriting is crucial and the worst part is I KNOW I’LL NEVER GET IT RIGHT NO MATTER HOW MUCH I REWRITE. At some point, I have to let go of my imperfect book — usually because the deadline is looming. Looking forward to reading another Louis Kincaid.

The part you put in all caps, Elaine….I suspect that is the primal scream within all of us. You bring up an interesting point that I hadn’t thought of before. That having a deadline (ie you have a contract to fulfill!) is a very compelling tool for not just forcing you to finish but also to be able to let go. But for those of us at TKZ who don’t have a contract or might be working on their first book, it is hard to know when to stop.

At some point, you have to give up rewriting and polishing and push the baby out for all to see and judge. (agents, editors, readers, reviewers). And there will always be someone who’ll say, “man, that’s one ugly baby you got there.” But you have to do it.

Ugh, authors in revisions unite! I’ve spent eight months rewriting the third book of my paranormal romance. The first draft was junk. I’ve rewritten huge chunks and heavily revised others. I didn’t know my villain’s motivation (or what my villain was) until the first draft was done. I’ve redone the climax. I’ve redone the beginning. I’ve redone the middle. I can’t pass it to my poor editor until I’ve gotten it fixed, but fixing it has been quite the job. I’m almost done, though, and I’m very pleased with the finished product. It reads like a coherent story now.

Hey Kessie,

Sorry I can’t buy you a nice martini or something at the end of your day. But you have my sympathies. I remember going into rewrites after we finished our second book with ice-cold terror because Kelly and I both realized (420 pages finished) that the villain was the wrong guy. It took two more months before we finished the rewrite. Luckily, our editor was able to accommodate the deadline, but as you know, that isn’t always the case. Thanks for dropping by!

This post is a keeper, Kris!

TKZ has taught me a lot about how to kick off those dreaded words: Chapter 1, page 1. But your point about a “well-aimed rock,” rather than a “boulder,” really resonated. That’s an important nuance we lose track of in our often-desperate bids to jump higher and yell louder to grab the reader’s attention.

Thanks for sharing your struggles. It’s heartening to hear that even authors with many publications and years of experience still grapple with the same old problems the rest of us do.

In some ways, it must be much harder to come up with stories that are fresh and compelling after you’ve done it so many times.

Looking forward to seeing the finished project!

Debbie,

In one sense, I think it gets a little easier when you are say, 10 books into a series. You learn things, you develop work habits, you know your hero better. But the deeper you get into a series and a career, the harder it becomes because I think if you’re doing this right, you always try to raise the bar for yourself with each book. If you don’t, you just start phoning it in and that is when a series begins to die. Maybe that’s also why so many series authors write the occasional stand alone because they need the clarity a break provides.

Except for Lee Child, who says he will never write anything but Jack Reacher. Dontcha just hate the guy? 🙂

Last week, I hit “the end” of my WIP. It’s connected to one of my series, but dives into a lot of uncharted waters (ugh, but it’s too early to kill the cliches). Some recurring characters, some new ones. I let it sit and now must go back and do all the things you’ve pointed out in this article. I’ve got the 1st 10 scenes printed out, sitting on my chairside table with red pen, sticky notes, (and thanks for the reminder about the ones on my PC), and a legal tablet. All I’m lacking is the guts to go sit in that chair and start working.

Thanks for the motivation this post provided.

Terry,

I so get your mood. I was happy to have a TKZ post due this weekend so I didn’t have to go open the Post-It note envelope. But today I have no excuse left. I have to go in and try to rewrite that opening chapter. Might have to hit the coffee shop for peace and no wifi today. Good luck with your rewrites!

Geart post. Love the tips.

Would suggest, though, for the newer writers especially, to frame, discount, filter and vet what those famous names advise. For example, Hemingway is wrong about “all first drafts are sh*t,” in an absolute sense. Child would disagree, certainly. The more you know about two things — the basics of craft (specific raw principles of dramatic theory especially, which embrace structure), and the general dramatic arc of your story (applying those principles), upon which you give your characters a chance to show up – the better the first draft will be. Up to and include a first draft that is a tweak and a proof/edit away from the one you submit. When we rewrite, we are recognizing where and why the story doesn’t align with those principles in an optimal way, and the revision seeks to bring it closer to them.

Add this tip: Add the words “for him/her” to any advice, anywhere. Including Hemingway and Child and all of here at KZ. Successful/famous authors tend to believe their own press clippings, and because some (not all) writing and story development processes are hard, they tell the world that it is always hard. For them. And to ignore everyone else. That’s bad advice.

Fact is, the process and the criteria and benchmarks applied to it are a) identical in intended outcome for new writers compared to experienced writers, and b) completely less-than-full-intuitive for new writers versus the applied instinctual learning curve of experienced writers.

This fall I heard a guy giving a keynote with a four million copy bestseller, and he had no idea how he had done that, and his advice — again, offered as “from on high” where he believes himself to dwell — is sacrosanct. It’s not. It’s just for him, first and foremost. And he suffered through it all.

Suffering is optional. A high bar is not.

… “up to and including”… rather than “include,” which demonstrates my own need for an editor.

Good points all, Larry. Maybe that’s why I felt compelled to add that last quote from Lee Child that advice from other writers will only take you so far. Sometimes, in fact, it can be counterproductive because a. There is no one way. b. rules can and often should be broken. And c. Not every writer is an effective communicator when it comes to teaching.

When I was working as a dance critic, one of the hardest parts of my job was getting dancers to articulate HOW they did what they did. Their art is so ephemeral and frankly, most of them could not begin to analyze it and put it in terms a layman observer could understand. It’s magic…and it drives those of us who can’t do it crazy trying to understand. But every once in a while, I got to interview an artist who did point the mirror inward — Violette Verdy, Suzanne Farrell and the great Erik Bruhn come to mind — and boy, was it fun to listen to them reveal how the alchemy works.

I have no choice but to rewrite multiple times. Cuz sometimes my Leprechauns come out in the middle of the night and “help” me. Sometimes it is good, but not too often does one find a military thriller being written from the perspective of a three foot tall Irish mercenary Leprechaun.

In all reality, each of my books goes through at least four rewrites. It has taken me ten books now to get to the point at which I realize the need for organization and keeping notes.

I’m in the same boat with you Basil…all our books improved on third or fourth rewrite. (Our second book went back into the grinder 10 times before our agent sent it out). And you are soooo right about keeping good notes, chronologies and such. It saves you so much work! (ie: now, what chapter is it that the first body is found? And where in the story did I put that bit about the evil coroner? Shoot…I’ll have to go back and search or read it all over again!)

Coming at this a day late – sorry.

I think it might be important to say, when writing and revising your first novel, you have to remember that you’re still developing as a writer, and that your skills are improving as time goes on. If you finish your novel but it doesn’t get sold right away, you may need to go back and revise and polish as your skills improve and you’re better able to see the awkwardness in your earlier writing.

The first novel of my series, which I’m querying now, went through many, many rewrites as my writing improved. At one point, I realized I had the bad guys just suddenly show up out of the blue. I had to set them up first. At another point, I realized my one character’s arc was flawed badly, so had to go back and revise to smooth it out and have it make sense. After many such revisions, the last rewrite I did was more of a polish – after writing several other stories, then going back to read this novel, I realized I used dialogue tags with abandon, even when they weren’t necessary for clarity. I went back through the novel, removing the random dialogue tags, and replacing as many of the others as I reasonably could with action tags rather than dialogue tags.

And, with each revision, I believe I’ve become a better writer. My first drafts tend to be much smoother now than they used to be. I’m better able to keep the arcs in mind as I write, so I can develop them as I go on. Perhaps that’s where Lee Child is now – he’s written enough that he can keep the story arcs in his head, so his first drafts are pretty well perfect. (Mine aren’t perfect, and I doubt they ever will be, because I don’t attempt perfection when drafting. That tends to freeze my brain. Mine are just better than they used to be.)

BJ: Good insights. Your line about having the bad guys show up “out of the blue” is important. Your villains (as you now know) but be a credible presence throughout the story before the reader catches on. I heard Phillip Margolin define this problem once as “the long lost uncle from Australia.” The character who never shows up until the end…

Well, that’s not very satisfying!

Thanks, such a useful and timely post for me. I printed it out. Currently, I’m editing my first/secondish draft, a process I usually enjoy, but this time it feels like I’m pulling out strands of my hair, one-by-one: an endless and painful exercise.

Don’t mention it Librarian! Glad to be of help. Keep at it. Yes, it is painful. And no, it never gets any easier. Does it help to know we are all there with you in the same boat?

Arggggh! That theme thing. My stories never used to have themes, but now I see they were incomplete without them. I was one of those people who thought theme questions were bs. And it definitely gets confused with plot–at least I confused it. I’m glad I’m not the only one who has to write and then spend lots of time figuring out what the story’s about.

Terrific post. ?

Pingback: Top Picks Thursday! For Writers & Readers 05-25-2017 | The Author Chronicles