I am busy with Edgar banquet duties this week, but I am confident you will enjoy this entry from my co-author and sister Kelly.– Kris.

By PJ Parrish

We write about crime, death, torture, corpses, graveyards and cops and we do it, usually, via Skype from homes 1,600 miles apart.

Despite the distance, it’s pretty easy for us to use our purple Post-Its to move a murder from chapter forty to chapter thirty five, because when you write fiction, you can kill anyone you want whenever you want and then finish off your glass of pinot and go to bed. You might lay awake thinking about the book — whether the plot flows logically or if you’re characters act rationally.

But occasionally, usually after a particularly grueling writing day, or one glass of wine too many, we sometimes find ourselves wondering what kind of people we are to be able to write this stuff and simply move on to something as a casual as walking the dogs or sitting down to a meat loaf dinner.

The answer is that no matter how graphic we may get, no matter how monstrous our villain or how many bullets we shoot across the page, in the end we know none of it is real. But once I had a chance to discover just what it’s like to write when it is real.

A couple years ago, I had both the pleasure and discomfort of assisting a new author on a true crime novel. He was a homicide detective who had a story he wanted to tell about a murdered officer but had no idea where to start. As a published author working on a new book set in his city, I was in need of technical information about his department and its history. Outside a bowling alley one night, we struck a deal. I would do a little editing for him. He would answer my police questions.

I thought it would be relatively easy. Like many authors, as PJ Parrish we have done light editing and critiquing for charity auctions and occasionally for friends, and I suspected this would be no different. But there were a few things I did not anticipate.

First was the officer’s passion for his story. His need to tell the story eliminated any of the usual author-ego issues, but it also made for the occasional dust-up between us. Usually, that involved his need for absolute realism and my desire to take literary license for dramatic effect. Second, I did not realize how different it would be writing about real events and the people who were even more real.

Over the next few months, as his narrative unfolded on my monitor, I found myself unable to let go of the story. I laid awake and thought about him. I started to think about the victim at the oddest times, seeing his face in every cruiser I saw on the city streets. All of this filled me with an increasing the sense of grief for an officer I never knew and a deepening respect for one I did.

I expected that at some point the repeated exchanges of the same chapters and scenes would work to dull the emotional impact. But it didn’t. It got to the point where I would postpone sitting down to edit until I knew I had a couple days to get over my depression afterwards.

Then I was given access to the crime scene photos. And I looked.

Everything became real. And I knew then that what I do with my stories, as passionately written and personally satisfying as they are, still makes for a pretty easy job. A beloved job, one I am lucky to have, but a job just the same.

As we neared the end, the officer’s passion never waned, and despite his heavy work schedule, he continued to revise and rewrite, always looking for ways to sand down the rough edges and splash some color on the players. I often imagined him working late into the night, hunched over a cluttered old desk, a half-can of beer nearby and a cigarette dangling off his lip as he pounded out a few more chapters.

Over the summer, he continued to send me pages and I continued to mark them with red ink. Slowly the book matured into something publishable. But as we entered the third act of the story could visualize this book on the shelves. Also I realized that as tough as it had been, I was going to miss it.

I was going to miss the author’s dedication and our strange, brief, and fragile friendship that survived only as long as we were writing. I was going to miss the people in the book because, in a way, telling the victim’s story allowed him to live once again, if only on pages and if only for a few months. And I would have liked to have known these people, many of them heroes in every sense of the word.

But as with all stories, once they’re told and ready to be sent into the world, we have to learn to let go. It’s never easy, even with fiction, but this was particularly hard. But we did it.

Over the years, I have thought a lot about what I took away from this experience that now seems a lifetime ago. It’s complicated, still. I know I will always reap a sense of satisfaction from helping a new author, and there is great reward in that process. And as someone who deeply respects law enforcement, there’s a large part of me that feels honored to have even penned even one single word of this book.

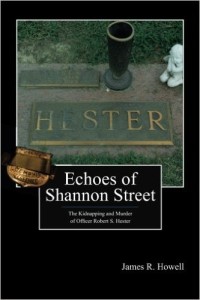

The book, Echoes of Shannon Street, never did find a traditional publisher, but I was okay with that because someone had told the story, and that counted for something. But about a year ago, I found myself wondering if the author had decided to join the growing ranks of the self-published. It took only one search to find it –- he had never changed the title -– and in one click, I was “looking inside.”

I was surprised to see he had changed the opening — yet again — adding new imagery, suspense, and edgy action that kept me turning the pages. I was not surprised to see that the author had kept rewriting and improving, long after we first typed “THE END” many years ago. But I was surprised to see something else.

My name. Not only as Editor, which is honor enough, but also written on the acknowledgement page was this:

“To Kelly Nichols, who taught me how to write.”

Postscript: Echoes of Shannon Street has been made into a documentary, titled “Shannon Street: Under a Blood Red Moon, A Memphis Tragedy,” with proceeds going to the 100 Club, which aids families of officers killed in the line of duty. The movie adaptation begins filming in the Summer of 2016, with a release date of January 2017. You can also see a powerful trailer with actual crime scene images here.