What is one of your treasured memories? Have you ever used it in a book?

Author Archives: Joe Moore

Can Storytelling Be Taught?

I posted some quotes below from bestselling authors on the craft of writing and the writer’s life. Some are funny, most are thought provoking, but the one at the top of the list from Willa Cather struck me as a topic for conversation here at TKZ.

From Cather’s quote, it would appear she believed that most of an author’s innate ability to write comes from how their lives were shaped in the first 15 years. We can read craft books, attend lectures, and follow as much advice as we have time to absorb on how to write books, construct stories, create characters, and world build, but there is also a part of who we are that makes up the total author.

For me, I grew up in a large family and our parents taught us how to laugh and we used our imaginations to tell stories and have adventures outside, not with video games. We even had skits we did for summer projects on our own. We did audio recordings of scripts I wrote as TV show parodies, complete with fake commercials. We chose video recordings (like a filmmaker) for class projects. We were all about theatrics and drama, for fun.

I wrote a lot of things and had always been drawn to the written word. My grandfather had been a big influence on me. He came to this country from Mexico after fleeing the revolution in his country. He wrote for the Hispanic newspaper, La Prensa, in San Antonio and he eventually managed the Alameda Theatre that brought in vaudeville acts and Mexican movie stars to the stage. As a young child I rode a pony across the stage of that theatre as part of an act.

Mostly I remember listening to my grandfather’s many stories. Some were real and others, not so much. What he didn’t know, he made up with a flourish. All of these influences became ways for me to tell a story and stretch my imagination.

I can see what influenced me as a writer in those early years, but I’d love to hear from you about your lives and formative experiences.

1.) What in your earlier years influenced you to become a writer?

2.) Do you agree with Willa Cather that most of a writer’s basic skills are experienced before 15 years of age?

3.) What do you think influences authors most in those first 15 years?

Quote For Discussion:

“Most of the basic material a writer works with is acquired before the age of fifteen.”

Willa Cather

Quotes On Craft & The Writer’s Life:

“All the information you need can be given in dialogue.”

Elmore Leonard

“Writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

E. L. Doctorow

“Get it down. Take chances. It may be bad, but it’s the only way you can do anything really good.”

William Faulkner

“People on the outside think there’s something magical about writing, that you go up in the attic at midnight and cast the bones and come down in the morning with a story, but it isn’t like that. You sit in back of the typewriter and you work, and that’s all there is to it.”

Harlan Ellison

HUMOROUS (I hope):

“A blank piece of paper is God’s way of telling us how hard it to be God.”

Sidney Sheldon

“Writing is easy. All you have to do is cross out the wrong words.”

Mark Twain

“Finishing a book is just like you took a child out in the back yard and shot it.”

Truman Capote

“I try to create sympathy for my characters, then turn the monsters loose.”

Stephen King

“It’s none of their business that you have to learn to write. Let them think you were born that way.”

Ernest Hemingway

“Writing is not necessarily something to be ashamed of, but do it in private and wash your hands afterwards.”

Robert A. Heinlein

“I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by.”

Douglas Adams

Obstacles, roadblocks and detours

When you write a story, whether it’s short fiction or a novel-length manuscript, there are always two major components to deal with: characters and plot. Combined, they make up the “body” of the story. And of the two, the plot can be thought of as the skeleton while the characters are the meat and muscle.

When it comes to building your plot, nothing should be random or by accident. It may appear random to the reader but every twist and turn of the plot should be significant and move the story to its final conclusion. Every element, whether it deals with a character’s inner or outer being should contribute to furthering the story.

In order to determine the significance of each element, always ask why. Why does he look or dress that way? Why did she say or react in that manner? Why does the action take place in this particular location as opposed to that setting? If you ask why, and don’t get a convincing answer, delete or change the element. Every word, every sentence, every detail must matter. If they don’t, and there’s a chance they could confuse the reader or get in the way of the story, change or delete.

Your plot should grow out of the obstructions placed in the character’s path. What is causing the protagonist to stand up for his beliefs? What is motivating her to fight for survival? That’s what makes up the critical points of the plot—those obstacles placed in the path of your characters.

Be careful of overreaction; a character acting or reacting beyond the belief model you’ve built in your reader’s mind. There’s nothing wrong with placing an ordinary person in an extraordinary situation—that’s what great stories are made from. But you must build your character in such a manner that his actions and reactions to each plot point are plausible. Push the character, but keep them in the realm of reality. A man who has never been in an airplane cannot be expected to fly a passenger plane. But a private pilot who has flown small planes could be able to fly a large passenger plane and possibly land it under the right conditions. The actions and the obstacles can be thrilling, but must be believable.

Avoid melodrama in your plot—the actions of a character without believable motivation. Action for the sake of action is empty and two-dimensional. Each character should have a pressing agenda from which the plot unfolds. That agenda is what motivates their actions. The reader should care about the individual’s agenda, but what’s more important is that the reader believes the characters care about their own agendas. And as each character pursues his or her agenda, they should periodically face roadblocks and never quite get everything they want. The protagonist should always stand in the way of the antagonist, and vice versa.

Another plot tripwire to avoid is deus ex machina (god from the machine) whereby a previously unsolvable problem is suddenly overcome by a contrived element: the sudden introduction of a new character or device. Doing so is cheap writing and you run the risk of losing your reader. Instead, use foreshadowing to place elements into the plot that, if added up, will present a believable solution to the problem. The character may have to work hard at it, but in the end, the reader will accept it as plausible.

Always consider your plot as a series of opportunities for your character to reveal his or her true self. The plot should offer the character a chance to be better (or worse in the case of the antagonist) than they were in the beginning. The opportunities manifest themselves in the form of obstacles, roadblocks and detours. If the path was straight and level with smooth sailing, it would be dull and boring. Give your characters a chance to shine. Let them grow and develop by building a strong skeleton on which to flesh out their true selves.

Notes from Thrillerfest 2014: The FBI Seminar for Writers

I just returned from the pre-conference, full-day seminar for writers at the FBI. There was a long waiting list for this popular workshop, so I was thrilled to attend! We met top FBI officials for the New York Field Office, including George Venizelos, Assistant Director-in-Charge. The session was jam-packed with presentations by the Special Agents in Charge of the New York Field Divisions, including Criminal, Special Operations/Cyber, Intelligence, and Counterterrorism.

Working with the FBI as a writer

We received a useful handout called WORKING WITH THE FBI: A Brief Guide for Writers. It describes how to request assistance from the FBI for a literary project. The Investigative Publicity and Public Affairs Unit (IPPAU) of the FBI reviews written requests for assistance on a case-by-case basis.

In case you missed it

If you’d like to learn more about the FBI, various Field Offices offer a 10-week Citizens Academy. Follow the link for more information.

Your favorite FBI story?

What’s your favorite portrayal of the FBI in books or film? I like following the fictional characters of the Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU) in CRIMINAL MINDS.

Release of Unlikely Traitors

It’s an exciting week for me with the release of Unlikely Traitors, the third in my Edwardian mystery series featuring Ursula Marlow. It’s been a long time coming and I’m thankful my readers no longer have to wait to find out what happened after the unexpected ending to The Serpent and The Scorpion (but don’t worry I’m not going to give it away – no spoilers here!)

The inspiration for Unlikely Traitors was a classic ‘what if’ scenario that came out of my research on Irish history. Ever since I was a teenager, I’ve been obsessed with the history of ‘the troubles’ in Ireland (I certainly disconcerted the librarian at our local library by asking for a copy of Bobby Sands’ poetry when I was ten years old…)

While researching the issue of Home Rule for Ireland (which was, not surprisingly, an ongoing controversy in Edwardian England) I found references to Sir Roger Casement and was immediately intrigued. Casement was an Irish born diplomat who was knighted by King George V in 1911 and hanged for treason in 1916.

Prior to the war, Casement was most famous for having exposed illegal slavery in South America and the Congo but when he returned to England (and despite his Protestant roots) he became a fervent supporter of Irish Independence. The outbreak of the First World War only cemented that fervour and, after traveling to Germany to secure aid for an armed Irish uprising against Britain, Casement was arrested and subsequently executed for treason.

Immediately I wondered – what was therefore happening in Ireland before the outbreak of the First World War? What if people had been attempting to get armaments and aid from Germany in support of an Irish Republic before war broke out? Turns out my “what if?” scenario wasn’t too far from the truth.

By 1912, Ulster was a powder-keg. Divided between the protestant pro-Ulster forces and the Irish Republicans, both sides were seeking to arm themselves to defend their opposing political positions. Within the pro-Ulster movement there already was a secret committee established to buy arms from abroad to resist any moves toward home rule or Irish independence. On the Irish Republican side, the Edwardian era provided fertile ground for resistance, rebellion and frustration over stalled Home Rule efforts. By the time I had finished my research, I knew that my third Ursula Marlow book would deal directly with tensions over Home Rule and the murky past of some of Ursula’s closest friends (particularly when it came to support for Irish Independence). I also knew that in the third book, the stakes for betrayal had to be higher than they’d ever been before.

So an exciting (and, I confess nerve-wracking) time for me as Unlikely Traitors is released into the world (first as an ebook then in print on August 12th). For me it’s the culmination of a “what if?…” scenario.

I wonder, how many “what if?” questions have led you, TKZers, to a new book or work in progress?

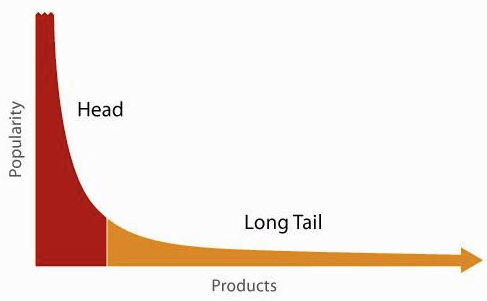

How to Keep the Long Tail Wagging

Summer Reading

Reader Friday: Time Travel

The Tell-Tale Heart

By Elaine Viets

Stephenie Meyer said the Twilight saga came to her in a dream. Stephenie slept her way to success when she dreamed about a teenage girl and a vampire who loved her but lusted for her blood.

I dream about my novels, too, but so far none of my dreams have made me an international bestselling author.

The ideas seem so good at three a.m. I wake up, flip on the nightstand light, and scribble them down, then fall back to sleep, certain I have a career-making revelation.

Daylight tells another story. One note I wrote at two a.m. said, “Call California.”

The whole state?

Sometimes I write down chapter openings or endings. In the morning, I can’t read my handwriting.

That’s frustrating. But there is a solution.

I read about Otto Loewi, an Austrian scientist who wrote down a ground-breaking idea – then couldn’t read his handwriting.

Otto is mentioned in “The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons: The Tale of the Human Brain as Revealed by True Stories of Trauma, Madness, and Recovery” by Sam Kean. The nonfiction tale is highly entertaining, but you may not be too Kean on reading the part about brain-eating cannibals at dinner.

Anyway, Otto Loewi was fascinated by experiments with frog hearts in salt water, Kean wrote. “A frog heart removed from the frog and plopped in salt water will beat on its own inside the solution.”

Loewi first heard about the experiments in 1903, but forgot about them until 1920, “albeit under odd circumstances. The night before Easter that year, he nodded off while reading a novel. A Noble-worthy experiment flashed before him in a dream, and he awoke, groggy, and jotted it down.

“The next morning he couldn’t read his handwriting. Annoyed, then desperate, he pored over every jot and tittle. All he could remember was the moment of euphoria, the moment when everything made sense. He retired to bed crushed.

“At three o’clock that night the dream returned. Loewi awoke and, rather than risk another loss in translation, scampered to his lab. There he etherized two frogs.”

Talk about heartless.

Loewi “slipped their cherry-sized hearts into two separate beakers of saline, where they beat and beat and beat and made little waves against the glass. One heart had its nerves still attached, and when Loewi sparked certain nerve fibers, the beat slowed down, as expected.”

Now Loewi’s experiment takes on Frankenstein overtones.

“It was the next step that made him tingle,” Kean said. “He sucked up saline from inside the first heart and squirted it into the other beaker. The second heart slowed down immediately. He then sparked some different nerve fibers on the first heart and sped it up. Another saline transplant made the second heart speed up, too – exactly as he dreamed.

“Loewi concluded that the nerve, whenever it was sparked, was spurting out some chemical. The chemical then got transferred to the second heart when he transferred the saline.”

This experiment definitely jump-started Loewi’s career. He won a Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1936.

Keep on dreaming for success – but don’t forget to wake up.

Avoiding Info Dumps

An info dump is when you drop a significant amount of information on the hapless reader. This can take various forms. As my editor’s recent comments indicate, even I am not immune to this fault. So what different formats might this problem take? Check these out:

Overzealous Research

You love your research, and you can’t help sharing it with readers. Here are two examples from my current WIP. The first paragraph is the original. The second one is the revised version.

Example One:

“The company built houses and rented them to the miners and their families. Single men would have shared a place together, eight to twelve of them in one dwelling. The homes were shotgun style. You could see in through the front door straight back to the rear. Since the miners worked twelve hour shifts, they weren’t all home at the same time. The rent was taken out of their paychecks.”

“The company built houses and rented them to the miners and their families. Single men often shared a place together. Since they worked twelve hour shifts, they weren’t all home at the same time.”

Example Two:

“The Colorado River Compact of 1922 divided the waters of the Colorado River between seven states and Mexico. Getting it to the farther regions of our state proved difficult. Thus was born the Central Arizona Project Canal, or CAP as we call it. This required pipelines and tunnels to move the water. That can be costly, which is why our cities obtain most of their water supply from underground aquifers. Groundwater is our cheapest and most available resource.”

“The Colorado River Compact of 1922 divided the resource between several states. The Central Arizona Project Canal, or CAP as we call it, uses pipelines to move the water to the far reaches of our state. That can be costly, which is why many of our cities obtain their water supply from underground aquifers. Groundwater is our cheapest and most available resource.”

Laundry List

Any kind of list runs the risk of being tedious. Here’s a litany of symptoms you might get after being bitten by a rattlesnake:

“You’d have intense burning pain at the site followed by swelling, discoloration of the skin, and hemorrhage. Your blood pressure would drop, accompanied by an increased heart rate as well as nausea and vomiting.”

As this passage wasn’t necessary to my plot, I took it out. Be wary of any list that goes on too long. Here’s another example:

He counted on his fingers all the things he’d have to do: get a haircut, buy a new dress shirt, make a reservation, call for the limo and be sure to stop by a flower shop on the way to Angie’s house.

Do we really need to know all this, or could we say, He ran down his mental to-do list and glanced at his watch with a wince. Could he accomplish everything in one hour flat?

Dialogue

Here’s a snatch of conversation between my sleuth, Marla the hairdresser, and her husband, Detective Dalton Vail:

“I’m going to talk to our next-door neighbor, who happens to be the Homeowners’ Association president,” Dalton told her. “Wait here with Brianna. Since my daughter is a teenager, she won’t understand the argument you and I had yesterday with the guy.”

“Yes, isn’t it something how he made a racist remark?” Marla replied.

“I thought it was kind of Cherry, the association treasurer, to defend you.”

This dialogue could have come from Hanging by a Hair, my latest Bad Hair Day mystery. But why would I have Marla and Dalton talking about something they both already know? This is a fault of new writers who want to get information across. It’s not the way to go, folks. Show, don’t tell. In other words, show us the scene and let it unfold in front of us. Don’t have two characters hack it to death later when they both know what happened. Now if one of these participants were to tell a friend what went down, that would be acceptable.

No doubt you’ve run across info dumps in your readings. Can you think of any examples or other forms this problem might take?