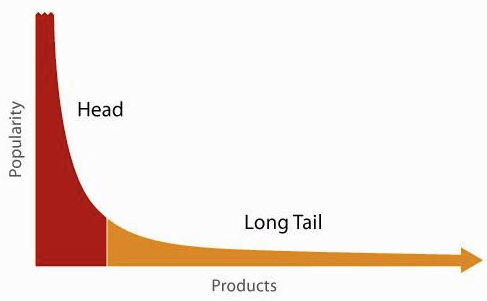

There’s been a lot of blogspace this week dedicated to the “long tail.” If you’re unfamiliar with the concept, see my post here.

The long tail is simply a way of describing a line of product that remains available for consumers. For books, it is the backlist. It’s become a relevant topic because now, in the digital world, books are “shelved” forever.

Recently there’s been some commentary on how just having a long tail online is not any help with discovery. That much is true. You still have to provide a way for readers to find your offerings.

This is the big challenge for traditional publishing right now. It the “old days” (pre-2007), big pub got books into bookstores and bought prime real estate for the titles it wanted to push. If a name was big enough—like Stephen King—a reader could also find a lot of his backlist sitting on a shelf.

Unfortunately, this was not the case for the midlist writer. Usually their frontlist title went to a shelf, spine out, and if the book didn’t catch on the bookstores would be less willing to buy the next. The publishers, who are after all in business, would usually not “throw good money after bad,” and thus a writer’s second book got only minimal treatment. Then the author disappeared from the shelves. Career over or consignment to the backwaters of small publishing.

Enter the Kindle and digital self-publishing. In those early years (what I call the Konrathian period), it was common to hear the naysayers opine that this was a blip, that only a very few authors would make any kind of money at this, and that it would unleash a “tsunami of crap” that consumers would be unable to wade through.

Well, we now know that early opinion is the bunk. We moved quickly to the Entrepreneurial period (see above link). Now every week it seems we hear about another self-published writer making really good money at this game.

It’s even possible that a debut self-pubber will smash through in a big way. As Hugh Howey recently stated:

[D]espite what some experts would have you believe, self-published authors are still breaking out with their first works. AJ Riddle and Brenna Aubrey are two examples, and the current bestseller lists on Amazon are loaded with new self-published authors you’ve never heard of. Andy Weir’s THE MARTIAN sold a ton of copies and was picked up by Random House and 20th Century Fox. This was a debut novel, and Andy hasn’t published anything since. He succeeded through self-publishing faster than he would have landed an agent if he went the traditional route.

But most of the time real bank is being made by productive writers who are developing that long tail. Which gives rise to a few thoughts for my fellow scribes:

1. Make sure the tail is worth wagging

Quality makes a difference. I’m not talking about some literary standard kept in a secret vault in an underground bunker below the offices of the New York Review of Books. I’m talking about making whatever you choose to put your keyboard to the best it can be. Don’t formulate this opinion on your own. Please refer to a post wherein I explain how to know you have a quality product. See also Jodie’s list of beta reader questions.

2. Pay for a trumpet blast

There are several e-book deal alert services out there worth your investment. The reigning king is BookBub. A listing there is tough to land, but if you do it’s the best advertising money can buy. Check out their submission tipsand keep trying. Other good services are Kindle Nation Daily, BookGorilla, eBooksoda, Ereader News Today, and Pixel of Ink.

Keep trumpeting your backlist on a rotating basis with these services. Don’t worry if you don’t make back every dollar of your investment. A percentage of these new readers will be of value down the line, as repeat customers.

3. Consider perma-free

If you have written a series of books, one strategy several recommend is making that first book free. That way there’s no cost barrier at all for readers to get started on the series. It’s a virtual guarantee that a percentage of the readers will go on to buy one or more of the related titles.

That’s happened with my historical series. Book #1, City of Angels, is free on Amazon. When I made the change last month, several blogs that announce freebies got wind of it––without any effort on my part. I saw a huge spike in downloads and the book reached #26 in the free Kindle store. There has indeed been a nice uptick for the other books in the long tail. My sales chart for all the other titles looks like the heart monitor of a patient going from stable to good condition.

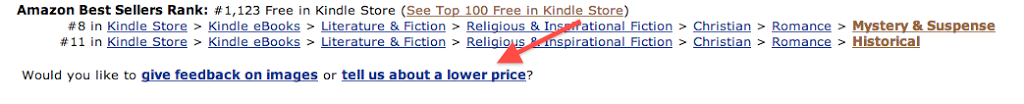

Perma-free is a strategy that, so far, Amazon does not discourage. To qualify your book must be offered for free on Kobo, iTunes or Barnes & Noble. You can accomplish this via Smashwords, but I simply did it via Kobo, which allows you to set “free” as a price. Then you go to your book’s page on Amazon and hit the “tell us about a lower price” link and follow the instructions.

4. Put your marketing on auto-pilot

The first six months of this year have been, far and away, the best for my self-publishing stream. I attribute much of that to setting up a marketing calendar at the beginning of the year and simply following that plan each month. I spread out my paid placements, KDP Select offerings, social media and e-mail notifications so I know what to do automatically.

5. Keep adding to the tail

Finally, and most important of all, keep adding content to the long tail. People can’t buy what isn’t there.

Do all this, and soon you’ll be able to say to your less-productive colleagues what the fox said to Otis: