Another courageous author has submitted the first 400 words of a work-in-progress anonymously for critique. Read and enjoy. See you on the flip side with my comments, then join me with yours.

PROLOGUE

Waterford, MN

June 4, 1994

By the light of the moon you can catch fireflies, or sit by a campfire watching the embers drift upward toward the stars. By the light of the moon you can stroll down a dirt road, or just sit on a back porch with a tall glass of iced tea. By the light of the moon you can propose marriage, or just leave your lover.

And by the light of the moon, if you have a shovel, you can try to bury your past.

That’s exactly what Jack Cicero had in mind, on this night in early June. The sun had already dipped below the horizon, and the full moon was threatening to make an early appearance. As he ducked under the oak trees, darkness shrouded him, causing him to have to use his flashlight which lit up the area like a beacon. All of his senses went into high alert. He pushed his thick eye glasses tighter on his nose. He strained his ears to listen for the sounds of approaching cars. The night was silent except for sounds of the Snake River choking itself on the rocks in its path; and the pounding of his own blood in his head.

He pushed on not willing to test his luck. He spied a large rock under the trees, and set the flashlight down in such a way as to shield its light from the road. If he heard anything, he could grab it in an instant and kill it.

He picked up his shovel, and cursed and groaned as he stabbed the soft earth at the base of the rock. He had to hurry, because this moon was a reluctant, silent witness rising higher in the sky, threatening to expose him. Although she tried, the full moon failed to penetrate the thick oaks overhead. But that didn’t make Jack feel any better. Despite the cool night air, he was breaking a sweat. He swore and picked up the pace. He was in a race to put everything behind him, closing one chapter so that he could open another.

With a groan, he hefted one final shovelful. Then he patted the dirt down and scraped some of last fall’s dead leaves over his handiwork. For a moment he thought that he might actually vomit. He dropped to his knees, leaning against the large rock and bent his head. A single tear rolled down his cheek, soaking into the sandy soil below. A final act of contrition. He wiped his face with his sleeve, pushed off of the rock and stood up. It was done. But Jack knew that no matter how much he could try to hide the past, it could come back to haunt him. He’d always be looking over his shoulder for someone to figure out his secret and expose him. Considering he knew just about everyone in Waterford, the list of possibilities was longer than the river itself.

FEEDBACK

OVERVIEW: At first reading, I liked this introduction because it stuck to the action (for the most part) and did not slow the pace with back story or explanation. That takes discipline for an author to do this. The narrative is simple and pulls the reader into the story with its mystery. Well done. But as I got into this on a 2nd and 3rd read, I found things I would edit if this were mine. This author shows promise and if the following items are addressed, I would keep reading.

THE START: I understand what the author intended with the first paragraph – to set the stage with a light and breezy beginning of harmless imagery before the reader is shocked once they realize the story will take a dark turn. Who’s POV is this? No one’s. It’s omniscient before the POV becomes that of Jack. This tactic–and the use of YOU–pulled me out. If the story is set up properly, where we see Jack in the dark with a shovel, he could be doing ANYTHING until we learn what’s happening and the mystery begins. The shock factor would be presented in another way, without the need for the faux lead-in.

THE ACTION: What is Jack doing? He’s got a shovel and a flashlight, but it doesn’t appear as if he’s burying a body because he’s not carrying anything else. Is he digging something up? He starts by digging into the ground with his shovel but ends by patting down a mound of dirt and pushing leaves over the pile to hide what he did. The transition from start to finish didn’t describe enough for me to understand what he’s actually doing. With the vagueness, the reader might make an assumption that would prove false later on, and the author takes a chance of alienating the reader if this is not made clearer. I also wondered why Jack would pick a spot by a road where he can be seen with his flashlight. If he’s got a choice and wants to be secretive, why risk a location where he can potentially be seen? I know the risk of getting caught adds to the tension, but maybe there would be a way for the author to explain why Jack picked the spot (even if it meant risk of discovery) and still leave an element of mystery.

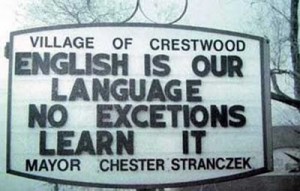

WORD CHOICES: In 3rd paragraph, “The night was silent, except for the sounds of….” If there are sounds, the night can’t be silent. The night might be “still” or “quiet,” but not silent if noise is heard.

In 5th paragraph, calling the moon “she” pulled me out and made me wonder if another character had stepped into the scene.

In 5th paragraph, the moon can’t be a “reluctant” witness to anything, but in one line the moon is shining on him, threatening to expose him, then in the next sentence, that description is contradicted by this – “the moon failed to penetrate the thick oaks overhead.” (Oaks are usually ‘overhead’ too. Directional words like up, down, overhead should be scrutinized during the edit process. They can usually be deleted.)

I’m not a fan of the word THAT. It’s often unnecessary and can be eliminated.

DESCRIPTIONS: This might be nit picky, but this phrase pulled me out of the narrative and made me wonder if there would be a better way of describing what is happening. This comes across as TELLING to me and could be more effective.

As he ducked under the oak trees, darkness shrouded him, causing him to have to use his flashlight which lit up the area like a beacon.

“The area” is actually the ground but what’s on the ground? How does the light play across it? it might be a more effective line if the author could get the reader to actually see the effect of the light, rather than merely saying it “lit the area.” Do the shadows of spindly grasses elongate and move as the light passes over it? The effect could add a creep factor. What sound do they make in the wind…for a guy who is already nervous?

PASSIVE VOICE: One of my favorite TKZ posts of all time came from Joe Moore in Jan 2012 – Writing is Rewriting. A great overview of the draft and edit process. Below are some examples of passive writing. My first pass at editing is to delete and tighten my sentences into succinct and clearer writing. Many readers might not pick up on the passive voice, but authors should strive to hone their craft and challenge themselves with each new project.

3rd paragraph: “was threatening” should be ‘threatened.’

5th paragraph: “was breaking” should be ‘broke.’

Last paragraph: “could try” should be ‘tried.’

PARAGRAPH LENGTH: I prefer to give the reader some white space so the paragraphs don’t appear laden and heavy as they look ahead. A heavy paragraph could encourage a reader to skim. As Elmore Leonard (RIP) once said – “Try to leave out the part readers tend to skip.” I often break up longer paragraphs into 3-4 sentences and change the length of those sentences to create a natural cadence if the words were spoken aloud.

FOR DISCUSSION:

What about you TKZers? What constructive criticism would you give this author?

HOT TARGET – AMAZON Kindle World $0.99 – DISCOUNTED (Book 1 of 2)

Rafael Matero stands in the crosshairs of a vicious Cuban drug cartel—powerless to stop his fate—and his secret could put his sister Athena and her Omega Team in the middle of a drug war.

TOUGH TARGET – AMAZON Kindle World $1.99 – (Sequel Book 2 of 2)

When a massive hurricane hits land, SEAL Sam Rafferty is trapped in the everglades with a cartel hit squad in hot pursuit—forcing him to take a terrible risk that could jeopardize the lives of his wounded mother and Kate, a woman who branded him with her love.