Yet the technical stuff might be needed for understanding the story, the situation, or the protagonist’s actions. Jargon may be essential for authentic-sounding dialogue.

What’s a writer to do? In my case, what’s an editor to do?

I’m a developmental and line editor, my full-time occupation for 44 years in publishing, starting in NYC. Coping with family transfers, I moonlighted for eight of those years by teaching writing for publication at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

I was also an instructor of writing for the University of Maine-Portland, then for SUNY-Rochester. One memorable summer I spent in the mountains near Seoul teaching conversational skills to South Korean teachers of English-as-a-second-language. They understood our grammar better than most Americans do.

DIGRESSION VS PROGRESSION

Notice that the preceding information is a digression. In fiction, that kind of content is called backstory. You probably keep reading such action-stoppers, at first, but after a while you’re likely to skim and skip ahead whenever the content seriously veers off topic.

Skimming and skipping are easy when only a paragraph of tangential information intervenes. Besides, most backstory and explanations can and should be cut. (Really.) But essential material that continually interrupts, especially if it’s technical, needs cutting and restructuring.

FORMAT AS AN EPIGRAPH

Catalyst: A substance that starts a chemical reaction but which is not itself chemically changed.

The above exemplifies a method I suggest of opening each chapter with a paragraph containing the least amount of technical data required by that chapter. Format the information as if copied from another source, using italics or a font different from your main text.

You can also set off the paragraph by indenting from both side margins. Instead of double-spacing, use one-and-a-half lines. Similar formatting and placement make it easy for readers to glance at the technical stuff, yet find it again if they later choose to see what it says.

LANGUAGE AND STYLE

In Southern Discomfort, Margaret Maron starts each chapter with an epigraph from an actual U.S. Navy manual on construction. Be sure the source you quote is in the public domain. (Government publications are.) Or concoct the “quotation” yourself in the style of a legitimate-sounding source.

The above definition of a catalyst is one of many chapter openings in 13 Days: The Pythagoras Conspiracy. This debut thriller by L. A. Starks follows the woman who must discover and stop a foreign plot to sabotage Texas oil refineries. The resulting gas shortages are shockingly real and unexpectedly deadly.

Definitions placed at the opening of many of Stark’s chapters allow the thriller’s pace to move like fire through an oil spill.

PSEUDO-AUTHORSHIP

A similar device is used by Deb Baker in her delightfully humorous, nontechnical Dolls to Die For mystery series. Each is supposedly excerpted from a book on doll restoring and collecting “authored” by a character in the series, the missing mother of the protagonist. Here’s an example:

When attending a doll show, a repair artist must be prepared for any doll emergency. Aside from standard stringing tools such as elastic cording, rubber bands, and S hooks … (and so on).

Each of Baker’s epigraphs is followed by this authentic-appearing credit line:

—From World of Dolls by Caroline Birch

ASIDES AS ANOTHER TECHNIQUE

Death Will Get You Sober is an insightful, engaging mystery by Elizabeth Zelvin, a psychotherapist experienced in treating alcohol addiction. Her first-person protagonist translates the jargon of the AA 12-step program with brief, unobtrusive asides within the narrative itself. The explanation below follows a line of dialogue spoken by a minor character obviously unfamiliar with acceptable AA practice:

“The man’s an asshole,” he told me.

“You mean you don’t like his sobriety,” I said. An AA way to register disapproval without actual name-calling. Step Four was taking your own inventory, not someone else’s.

Another example from Zelvin’s debut novel offers an even briefer, equally straightforward explanation:

“You take care of yourself,” she admonished me. “Don’t you dare go AMA before you’re discharged, and don’t get into any trouble.” She meant leaving against medical advice.

If you have your own examples of explanatory asides in third-person, or other effective techniques, I hope you’ll share them with me.

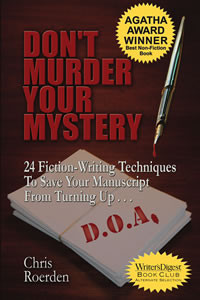

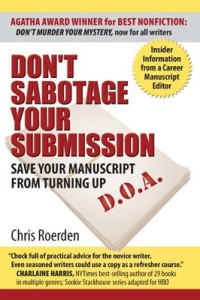

CHRIS ROERDEN wrote the Agatha Award winning, Anthony and Macavity nominated DON’T MURDER YOUR MYSTERY and its all-genre version, DON’T SABOTAGE YOUR SUBMISSION.

Ms. Roerden,

Enjoyed your talk at the Cary Library a few weeks back. Sorry there were so many people more intent on debating the evils of the industry than on learning how to be a professional. I liked what information I was able to glean from your talk (in between the “but how come he gets to get away with it???” crap). Thanks again!

Chris, thanks for your kind words about my book. A footnote to the second example: I originally used “AMA” without explanation, and someone at the publisher’s (I forget now if it was my editor or the copy editor) said readers wouldn’t understand it and asked for clarification. If I’d used “against medical advice” in the dialogue itself, it wouldn’t have sounded authentic.

Wonderful post! Thanks for using an example from my Dolls To Die For series. After seven published novels, I still rely on Don’t Murder Your Mystery to guide me through the tough spots.

It’s such a balancing act: providing enough information without stopping the story dead in its tracks, or leaving the reader saying “huh?”.

I’ve had to wrestle with this for my (well, Sarah Atwell’s) Glassblower series, and it’s made me think about a broader issue. Most current “hook” cozies feature a profession or craft that most people can imagine themselves doing. But glassblowing is not something you just dabble at, and few people are likely to try it. My strategy has been to convey my protagonist’s love of the craft, the excitement she feels when she’s working.

We’ll see how well that works.

Michael Connelly seems to have mastered the “info dump without dumping info”. I admire the way Harry Bosch seems to explain things — Connelly makes it seem the most logical thing on earth that Bosch would be thinking about the layout of the Parker Center, or the finer points of the investigation, when in reality, these would probably be so ‘old hat’ that he’d never really consider them.

I try whenever possible to stick a lay person into the scene as a foil for my characters to have to explain something.

As a reader, I enjoy some of the “puzzles” of reading “pulling KOD duty” and then figuring out from context that it means “knock on doors” — I’ll usually expect the ‘answer’ to show up within 4 or 5 paragraphs. I’ve had editors insist that I spell out the first use of an acronym, which drives me batty if it’s two people in the profession talking. I try to find another way to work it in.

And, with everyone thinking the stuff they see on tv is the way it is in real life, sometimes you have to “unexplain”.

I have to admit, I’ve never been good at reading chapter/scene headers and quotes at the beginning of chapters. (I skipped over them in textbooks too, so it’s just me, I think.)

Chris, thank you for being our guest today! Great post! I keep my copy of Don’t Murder Your Mystery by my side as a constant reference when I’m rewriting.

Thanks for the useful tips on providing technical information. When the setting is central to the story, it’s tough to know how much detail is appropriate, no matter how it’s woven in. As a reader, I am often fascinated by information that may be incidental to the story, but I’m a data junkie. As a writer, it’s hard to know how far readers want the author to go. Night Kill, my first mystery is set in a zoo and my “first readers” have been invaluable in defining how much they want to hear about wild animal behavior, natural history and how zoos operate. I love writing that stuff, but of course, the story must rule.

Ah, and since I used to work in a zoo, I’d eat it up!

I grew up in LA, and LOVE the way Michael Connelly use the city as a character in their books. I follow Harry and Elvis all over town.

Ms Roerden,Thanks for the discussion. I don’t have a copy of Don’t Murder Your Mystery, but will be at the book store tomorrow to add it to my collection.

I have a business thriller, In the Essence of Time, I’m working on where the central plot revolves around legal technicalities that have to be explained. Perhaps this book will keep me from murdering this novel.

Thanks,

Johnny (Sir John) Ray

Great post, Chris. Everytime I hear you speak or read something you wrote, I learn.

Hugs,

Sue Ann

Thanks so much for the post. I’m working on a couple short stories and a novel for a character that is in environmental consulting, and I continually grapple with this issue. Like others, I love to write the detail in but, then have to go back and pare it down to the bare essentials for the story.

I have been using the client or other non-tech character, as a sounding board for what tech detail is needed for the plot. It provides the info without being a boring narrative paragraph, which I know I personally will skip when reading.

Really enjoyed your discussion during Mentor MOnday awhile back.Your help is invaluable for we newbie novelists!

Kenna

Hi, I’m posting these replies for Chris, who had trouble connecting to the Internet…

To jnantz:

It’s a crazy industry, isn’t it, and the process of breaking in is so different from being a consistently top-selling author. Just last weekend when I did a Skill Build for Writers at the Greensboro, NC, library, Edgar-winner John Hart said he was making more money now than when he worked as an attorney!

Sorry the discussions you mention took time away from the new info I wanted to share. Actually, the impetus for my writing DON’T MURDER YOUR MYSTERY came from not being able to share enough info in two-hour workshops–workshops I’d been presenting for many years before even thinking of putting what I had to say about writing and submitting into a book. At least the book is more accessible to more writers than any number of personal presentations.

Chris

To Liz Zelvin:

You’re absolutely right about the need for authentic dialogue between colleagues, even when it means questioning how to avoid puzzling the reader. In some cases, meaning comes from the context, but in other cases, a first-person narrative is ideal for adding a brief clarification. You do these so well, often with gentle humor—as in the first example of yours I quoted. I look forward to your next book in this series.

Chris

Hi Deb Baker:

Thank you for your good words about DON’T MURDER YOUR MYSTERY. I’m so proud of you for the seven wonderful books you’ve turned out, both in the Dolls To Die For series and the Yooper Mysteries featuring my favorite hoot, Gertie Johnson.

Chris

To Sheila Connolly, aka Sarah Atwell:

I’m so glad you commented on your Glassblower series. I bought Through a Glass, Deadly six months ago, yet it sat on my nightstand, in very good company, until yesterday, when your comment made me move it to the top of the to-be-read pile. (My excuse is that I’ve been touring since March, and don’t dare begin a book

More from Chris…

To Ann Littlewood:

You’re so right that the story must rule. The trick is not to avoid explanation but to pare it down to its essentials. If that means offering an incomplete or too-sparse way of dealing with a situation, remember that you do not want to satisfy your readers, you want them to want more—for which they have to read more and hope that clarification will come a little later in the context of what happens next.

Readers are not dumb and don’t need complete explanations. It’s not easy to maintain the “less is more” approach, but it’s usually much more successful than covering a peripheral or supplementary topic in detail. Often, a specific example is perfect, and a good way to offer such an example is through some action taking place, even if the action is extremely minor (and of course, brief).

I wonder if epithets would work for you, quoting passages from those wonderful signs in front of animal cages.

Chris

October 26, 2008 7:15 PM

To Terry Odell:

Funny you should mention Michael Connelly’s use of L.A. as a character in his books. I quote one of his descriptive passages of L.A. as an example of just such a setting-as-character technique in both my books for writers.

Well done.

Chris

October 26, 2008 7:26 PM

To Johnny Ray:

I think Steve Martini does a good job of explaining legal technicalities. After you read one of his books for the whodunit and why, read the same book again just for the techniques of how he handles your very issue.

Note, too, the tone of his protag’s voice as an effective part of that technique, and how conflict enters into his relationships with others. Try Prime Witness. I don’t admire all of Martini’s techniques, but I do the way he imparts legal information.

Best,

Chris

October 26, 2008 8:01 PM

To Sue Ann Jaffarian:

Thank you so much for your good words. I so enjoy your sense of humor and turns of phrase in your Odelia Gray series.

Keep it up!

Chris

October 27, 2008 9:46 AM

To Kenna:

Thank you for comments. Your method is fine, writing long, then revising short. Just be sure the client isn’t such a dork that lots of explanation is required. After all, uninformed readers who identify with your protag because s/he is a great character will also identify with the uninformed client, who has to be smart enough to “get it” when an explanation is short and sweet.

You’re light years ahead of other new writers who aren’t at all aware that their own fascinating detail can become a boring narrative to readers.

One thing I am seeing a great deal of in first-time manuscripts is over-explanation. Combined with too much backstory too early, the result is murder.

Best wishes,

Chris

I had an overdose of trying to make technical matter simple, in eight novels in the periodic table mysteries.

I know I didn’t always succeed, but I did try and was grateful for “Don’t Murder …”

I’m not a big fan of “She meant the … (fill in the blank)” after an acronym or a technical term is used. It sounds like an aside from another body and takes me out of the story.

I prefer to do it in dialog if it’s not too contrived with a straight man, or even leaving it and letting the reader put it all together herself and feel smart!

Chris,

I love your comments.I don’t usually read murder mysteries, but that is subject to change.

I love Sheila and Ann’s comments,the story must rule.I vividly remember being captured by the details in Atlas Shrugged.

I was confused by the reference to AMA in another comment. My assumption was that it meant American Medical Association.

JWW

Jay Hudson

One technique I use to deliver technical info is to not deliver it at all, but when the character is ready to use the device or whatever, they hope it does this or that, as they were told it would, but how it doe it is lost on them. I’ve found that how something works is rarely that important, only what it does, or is supposed to do, things do go wrong.

Margo thinks, (italics starts here) I hope this little bitty pistol thing they gave me really can make people look dead instantly, like they told me. If it doesn’t I’m in big trouble fast.