Last Christmas I watched the 1938 Henry Fonda movie called I Met My Love Again. The plot: A woman returns to her Vermont sweetheart ten years after running off to Paris with a writer. Those dang writers! Love ‘em and leave ‘em!

Joan Bennett plays the woman. She meets the writer during a snow storm. Her sleigh overturns and the horse runs off. She finds a cabin and knocks on the door. An Errol Flynn lookalike answers. He has a roaring fire going and a page in a typewriter.

Joan comes in and warms herself. They talk a bit, and he tells her he’s renting this cabin to get some writing done. This dialogue follows:

“You’re a writer?”

“Yes.”

“Do people really publish what you write?”

“Yes, the wrong people. You see, I’ve got to make a living, so I write trash to keep alive.”

She looks down at the page in the typewriter and reads:

Then I picked up the knife and sank the sharp steel blade into his chest. He sighed gently, and turned his great eyes – those eyes I once loved so – to mine. That was my first man.

CHAPTER TWO

I Go Straight

The writer admits:

“That’s the trash, a confession story, slated for the March issue of I Tell All. It’s the true story of a gal named Lyla Rigby. I am Lyla Rigby.”

I snorted. What a great example of the old bias against “writing for a living.” Such a “trashy” thing to do! A real writer wrote novels, labored over them, and did it mainly for art’s sake. Those who slummed in the world of pulp fiction were to be scorned, which is why many of them hid behind pseudonyms.

That kind of thinking was certainly widespread back in the day. But its tentacles still exist, as evidenced by the hissy fit Harold Bloom threw several years ago when Stephen King was given a major literary award. There is also a steady vibration of snark in articles such as The Death of the Artist—and the Birth of the Creative Entrepreneur. Here’s a clip:

Yet the notion of the artist as a solitary genius—so potent a cultural force, so determinative, still, of the way we think of creativity in general—is decades out of date. So out of date, in fact, that the model that replaced it is itself already out of date. A new paradigm is emerging, and has been since about the turn of the millennium, one that’s in the process of reshaping what artists are: how they work, train, trade, collaborate, think of themselves and are thought of—even what art is—just as the solitary-genius model did two centuries ago. The new paradigm may finally destroy the very notion of “art” as such—that sacred spiritual substance—which the older one created.

The article posits that the concept of the artist changed drastically in the 20th century. “As art was institutionalized, so, inevitably, was the artist. The genius became the professional.” This awful turn of events has led to the crumbling of “mediating structures” like publishing companies, who were once the gatekeepers.

[W]e have entered, unmistakably, a new transition, and it is marked by the final triumph of the market and its values, the removal of the last vestiges of protection and mediation. In the arts, as throughout the middle class, the professional is giving way to the entrepreneur, or, more precisely, the “entrepreneur”: the “self-employed” (that sneaky oxymoron), the entrepreneurial self.

Which, the article concludes, leads inexorably to the death of art itself:

It’s hard to believe that the new arrangement will not favor work that’s safer: more familiar, formulaic, user-friendly, eager to please—more like entertainment, less like art. Artists will inevitably spend a lot more time looking over their shoulder, trying to figure out what the customer wants rather than what they themselves are seeking to say.

There it is, the old “art v. commerce” angle, complete with hidden assumption that something popular cannot be art, and something artistic should not be popular.

Yet Dickens, Dumas, Dostoevsky—The D Boys—all wrote great artistic works for a popular audience. Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe certainly desired a wide readership. In the pulps, Chandler and Hammett and Dorothy Hughes had the readers, but also said meaningful things about the mean streets and the human condition.

None of these authors wrote without the desire for financial return. As Dr. Johnson so eloquently put it, “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.”

Out on the edges, sure, you have the solo artist who doesn’t give a rip what others think. And so creates experimental pieces that don’t sell, except on rare lightning-strikes occasions.

On the other side of this divide are those who “write” monster porn (yes, it really exists) and somehow find people willing to pay for it.

But in the great in-between are those who want to entertain an audience. For some that is enough. Others want to add a little more heft to their style or theme, and that’s a good thing. Still others want to transcend genre conventions and reach for the stars. I especially like that.

So isn’t it about time to put the “art v. commerce” debate to bed? It was okay for cocktail parties in 1965—“Honestly, are you comparing Mailer to Hemingway? How droll.”—but was it ever really a substantive discussion?

How many artists are there, truly, who don’t care a fig about income? (By the way, if you do want to “suffer” for your art, it’s very easy not to make money, so have at it.)

Is the disdain for “popular art” productive or even valid?

And here’s the big one: how concerned should we be about the “crumbling” of the mediators—publishing companies, critics, agents?

The discussion may now begin.

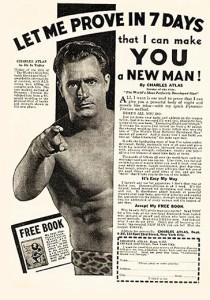

What would be the male analogue? This guy?

What would be the male analogue? This guy?