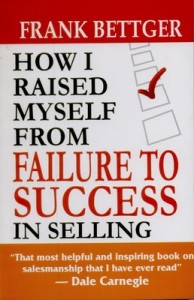

The rah-rah headline for today’s post is borrowed from a book I read as a young man, How I Raised Myself From Failure to Success in Selling by Frank Bettger. It’s considered a classic of sales-training lit. But lots of folks have given the book props for helping them get ahead in other professions, too.

The rah-rah headline for today’s post is borrowed from a book I read as a young man, How I Raised Myself From Failure to Success in Selling by Frank Bettger. It’s considered a classic of sales-training lit. But lots of folks have given the book props for helping them get ahead in other professions, too.

The headline is also apt because I definitely thought myself a failure as a writer when I was in my twenties. The stuff I wrote didn’t work the way I wanted it to, and I was told that’s because you have be born a writer. You can’t learn how to do it.

For ten years or so I accepted that I would never make it in this business.

So I did some other things. I moved to New York to pursue an acting career. Started doing Off-Broadway, Shakespeare, avant-garde. But after awhile I wondered why I wasn’t being offered a starring role in a movie like Raiders of the Lost Ark (they gave it to some guy named Ford).

During a visit back to L.A. I met this gorgeous actress at a party. Knowing I’d be returning to New York soon, I only waited two-and-a-half weeks to ask her to marry me.

Shockingly, she said yes.

After we were married I decided it might be a good idea for us to have one steady paycheck. Since Cindy was the more talented of the two of us, she continued with her stage work while I applied to law school.

In my third year at USC Law I interviewed with a big firm with offices in Beverly Hills.

Shockingly, they hired me.

Later on I opened my own office. And found out I had to be a businessman, too. I had to learn entrepreneurial principles. So I started to read books on business, and one of these was Bettger’s.

A few years went by and the desire to write, with me since I was a kid reading Tarzan of the Apes, came back to me. Bettger’s principles helped me along that path, too.

Frank Bettger was a former big-league ballplayer who went into the insurance game. After initial failures he started wondering if he really had what it took to be a good salesman. He decided to find out what others did. He began to apply a set of practices that helped get him to the top.

Frank Bettger was a former big-league ballplayer who went into the insurance game. After initial failures he started wondering if he really had what it took to be a good salesman. He decided to find out what others did. He began to apply a set of practices that helped get him to the top.

The first of these practices was enthusiasm. To sell successfully, you have to be enthusiastic about your product, your prospects, life itself. You need to exude joy, because the alternative is gloom, and gloom don’t sell.

Bettger noticed that if he didn’t feel enthusiastic, he could still act enthusiastic, and soon enough the feeling came tagging right along.

When I discovered you really can learn the craft, I got as excited as a man in the ocean who finds a plank to hang on to and then spots a lush island in the distance. It was enough to infuse joy and hope into my writing, and those two things alone started to improve it.

Another practice Bettger mentions is a system of organization. Make plans, record your results. When I got my first book contract I hadn’t thought through what I’d do for a follow-up. So I got organized. I began planning my career five years ahead, kept track of who I met with and pitched to, who I wanted to meet, and scheduled projects accordingly.

I’d already established the discipline of writing to a quota, but now I started keeping track of my output on a spreadsheet. Starting with the year 2000 I can tell you how many words I wrote on any given day, on what projects, and my weekly, monthly, and yearly totals.

Next, Bettger summarized the most important secret in sales: Find out what the other fellow wants, then help him find the best way to get it.

This got me thinking about pleasing readers. In college I was heavily influenced by the Beats (Kerouac, Ginsberg, et al.) Their writing was idiosyncratic and experimental. But I figured out early that what was idiosyncratic did not necessarily, or usually, connect with a large audience.

I knew I could write solely for myself, ignore genre, be hip (though a lot of the time it was artificial hip). But I wanted to make a living at this, so I backed up and looked for points where my own writing pleasure met with readers’ desire for a good story.

Still, I needed confidence this could be done. Bettger wrote that the best way to increase confidence is to keep learning about your business. Never stop.

The same holds true for writing, both the craft side and the business side.

If you are set on traditional publishing you need to know: What are publishing contracts like? What terms are you willing to accept … or, more importantly, walk away from? What are the characteristics of a good agent? What can you realistically expect in terms of editorial and marketing?

If you are going to self-publish, do you have a plan? Do you know what you need to know? Are you putting in a systematic effort to find out? Are you a risk taker?

In my business life I dedicated at least half an hour a day reading about business principles, thinking, and planning. I do the same thing in my writing life. I read every issue of Writer’s Digest. I enjoy books and blogs on the craft. My philosophy has always been that if I pick up one new technique, or see something familiar from another point of view, it’s worth the effort.

There’s a lot more packed into Bettger’s book, but I’ll close with the part that helped me most, both as a businessman and as an author. It’s his chapter on Ben Franklin’s plan for self-improvement.

In Franklin’s autobiography, he writes about his desire, as a young man, to acquire the habits of successful living. Franklin chose thirteen virtues, such as temperance, resolution, frugality, justice and so on. He made a chart and concentrated on one virtue for a week, ingraining the habit. That way, he could go through his list four times a year.

Bettger followed this plan by choosing thirteen practices that would help him as a salesman, such as sincerity, remembering names and faces, service and prospecting, and so on.

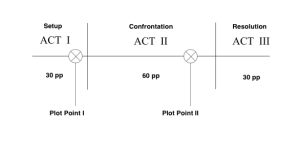

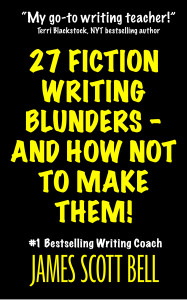

I did something similar with my writing. I formulated what I call the Seven Critical Success Factors of Fiction: plot, structure, character, scenes, dialogue, theme, and voice. By concentrating on these serially, I hoped to raise my overall game.

Bettger’s book helped me at two crucial points in my life––when I had to run a business, and when I made the decision to pursue the writing dream. In both pursuits there are challenges aplenty. Sources of inspiration are critical. I’m glad that ex-ballplayer was around to fire me up.

So what gets you enthusiastic about your writing? When you need an infusion of confidence, where do you turn?