I have a number of writing friends who are in one phase or another of a traditional career––still in it, sometimes hanging by a thread, a few dropped by their publishers. These friends all started in the “old system.” You wrote a book, got an agent, signed with a publishing company. Getting invited inside the walls of the Forbidden City was the only game in town.

I have a number of writing friends who are in one phase or another of a traditional career––still in it, sometimes hanging by a thread, a few dropped by their publishers. These friends all started in the “old system.” You wrote a book, got an agent, signed with a publishing company. Getting invited inside the walls of the Forbidden City was the only game in town.

Of course, that’s all changed. The indie revolution that began in earnest in 2008 has grown from healthy baby to active toddler to good-looking adolescent. It’s driving the family car now. It has some acne, sure, but the teeth are good and the body sound.

From time to time I’ll hear from one of my friends, asking for advice about which way to go. They may be near the end of a contract, or in new talks offering them lower advances and tighter terms. Here is some of what I tell them.

- Traditional publishing is still a viable option

To paraphrase Mark Twain, reports of the death of traditional publishing are greatly exaggerated. Yes, trad pub is in the throes of reinvention due to digital disruption. That process is slow, as it is for any large industry facing a shifting infrastructure. Rapid innovation has never been the strength of large industry. But they’re trying.

Traditional companies are also the only way to distribute print books widely into physical stores, including big boxes and airports. If that’s where you want your books to be then traditional publishing is your best shot.

Just understand that your shot is getting increasingly long. Because big bookstores are closing. There is tighter shelf space within those stores. Big boxes and airports are ordering fewer books, and therefore sticking with the big names like Lee Child and Janet Evanovich. While there has been a nice resurgence in independent bookstores, they can’t replace what’s being lost when a major chain store closes.

- I understand your anxiety

Being with a traditional house provides a level of security. When you’ve been working with the same people for a long time, there’s a comfort level. When you’re used to the system—editorial, design, distribution, marketing—the thought of switching to a place where you have ultimate responsibility for these things can be nervous time.

Many writers just “want to write,” and not worry about all that other jazz.

My advice is: don’t let anxiety be the tail that wags you. Think back to when you wanted to break in the first time. How nervous were you pitching to an agent? Getting rejected? Wondering if you had what it takes? Eventually, you broke through. You can do it if you go indie, too, because you have the added benefit of a track record. You know what you’re doing as a writer. You have readers who will follow you.

Writers always operate with a certain degree of fear. The trick is to translate anxiety into action, with a rational plan for where you truly want to be.

- Don’t think of traditional publishing as your nanny

Trad pub is about the bottom line, because it has to be. You can’t stay in business unless you make a profit. Publishers have to stay in business, and they will treat you with that in mind.

I tell my writing colleagues that a publishing company is not your nanny. If you don’t make them money they are not going to coddle you, make you breakfast, or tuck you in at night. There will continue to be very nice (albeit overworked) people within the company, who like you and want you to succeed. But it is the counter of beans who will determine your future at said company.

Now, if you’re making midlist money and your publisher continues to offer it, you may want to stay right where you are. One successful indie author misses several things about traditional publishing. Have a look here.

Fight for a fair non-compete clause. Your business partner owes you that.

But you should also learn to sing “It’s a Hard-Knock Life” like the orphans in Annie. I have several writing friends who have been “orphaned” over the years when their editor-advocate within a company moved on or was let go.

- Traditional contracts are tight

Traditional publishers are taking fewer risks these days. This is reflected in contracts many writers and agents find particularly onerous. Which is why the Authors Guild is calling for fairer terms. It’s a lovely thought. But it is slamming up against harsh reality. Big publishing simply cannot afford to be overly generous or induced to easily revert assets (i.e., books) back to authors.

It’s business. I hold no animus for a corporation that is trying to stay in business.

But you are in business, too. So be educated about contracts. Work with your agent on the terms you can live with, and those you can’t.

In a lengthy piece on this topic, Kristine Kathryn Rusch wrote:

[W]riters need to know what they’re up against.

They’re not signing up for a partnership with a production and distribution company like they had in the past. Mostly, these days, writers are signing with an international entertainment conglomerate that wants to exploit its assets for as long as possible…

When writers do business with an international entertainment conglomerate, they should be prepared to walk away from what initially looks like a good deal. Because, in most cases, the writers will lose the right to exploit that property themselves for the life of the copyright.

- Know your risk tolerance

Thus, what you really need to assess, right now, is your own risk tolerance. Are you willing to walk away from a sure, albeit smaller and more restrictive contract? Can you do without an advance? Do you have the patience it will take to build up an indie publishing stream?

You are taking a risk either way. Traditional publishing is a wheel of fortune. When you pay to play, you’re hoping your book will be the one on the wheel that comes up the big winner. If it does, it could be worth millions. It could be the next Harry Potter or The Fault in Our Stars or Gone Girl.

That’s what you’re playing for—a #1 bestseller slot, the movie deal, the airport placement, the Today Show appearance.

Of course, this sort of fortune happens to very, very few. Books that deserve to be there don’t ring the bell. Yes, your book could be the one, which is what lottery players say to themselves every time they walk into a liquor store or gas station mini-mart.

If you play and your books don’t make it, the cost may be several years of your writing life and possibly no reversion of rights. So be rational about your gambling. If you are you willing to risk all that for a spin of the wheel, then get the best terms you can and good luck to you.

- Know your freedom and creativity valuation

But here’s another thing to consider: how much do you value the freedom to write what you want to write and to publish when you are ready to publish? To try a different genre and not worry about branding restrictions and non-compete clauses?

Do you want to be creative more than you want to be secure?

Another thing: if you decide to stay traditional, you at least need a footprint in the indie world. Work with your agent and publisher about non-competing, short-form work to grow your readership.

It all comes down to making the decision YOU want to make, without letting a thousand anxious thoughts hack away at your dreams. So listen to counsel and advice. Talk things over with your agent, your spouse, your talking cat. Pray, if you believe there is divine benevolence.

Just don’t wait for certainty, because the only constant is change.

Just don’t wait for certainty, because the only constant is change.

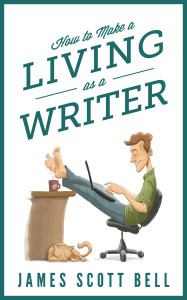

Traditional publishing will stick around and try to find its way forward. Indie publishing will continue to grow and diversify, and new options for writers who own their rights will appear. This requires constant vigilance and business savvy, which some writers don’t like. Don’t be afraid. The principles of success are not difficult to understand and implement. I wrote a whole book about that.

Whatever you decide, keep writing. I love what one of my favorite Hollywood writer-directors, Preston Sturges, once said. He was riding high in the early 1940s with a string of hits that still shine today. But he knew Hollywood careers are transient. “When the last dime is gone,” he said, “I’ll sit on the curb with a pencil and a ten-cent notebook, and start the whole thing all over again.”

As long as you write, you’re never out of the game.