My book Plot & Structure (Writers’ Digest Books) is the foundation. It was a labor of love from someone who was told you can’t learn to be a writer, that the ability to plot was something you had to have born into you, that you might as well sling hash if you think you can write for a living without “it” being in you from birth.

I believed that twaddle for a long time. I lost ten good years of a writing life because of the chuckleheads who said you can’t learn to write fiction.

When I sat down to try—because I wanted to be a writer more than anything, and just had to give it a go, even if I failed—I began by studying structure.

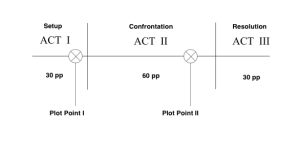

At the time, the big structure book was Screenplay by Syd Field. Field said there were three acts in a good movie, with Act I comprising the first quarter of the running time, Act II half the time, and Act III the last quarter. He then determined there were two “plot points” that occurred to move the action from Act I to Act II, and from Act II to Act III. His “paradigm” looked like this:

All well and good. But as I studied this out I got hung up on those plot points. What Field said they did was “spin the action around” in another direction. I could not figure out what that meant. Was it any random action? Because there are an infinite number of actions and an infinite number of directions a story can take.

Determined to find out what I was missing, I spent a year watching movies with a blank paradigm sheet in front of me. I divided the running time of a movie into quarters, and kept an eye on that first quarter, Act I, looking for the secret to the plot point.

I finally found it.

And dubbed it the “Doorway of No Return.” The key is this: Something pushes the Lead into the confrontation with death in Act II. The Lead has to be forced through, because no one wants to fight with death.

We want to stay in our nice, comfortable world and enjoy life as we know it.

We can’t let that happen to the Lead! A novel or movie does not become the story until the Lead is forced to fight death, which is what Act II is all about.

Not pushing the Lead through that first doorway is #14 of the 27 writing blunders I take on in my new book:

It’s a doorway of no return because the Lead can’t go back through the doorway to the old life. If he can, it’s not a true break into Act II.

When you do this right, the reader will go right along with you.

But if you don’t force entry into Act II, the story will feel weak. Unmotivated. Manipulative.

Note this, too. You must force that entry by the 1/5 mark of a novel or the 1/4 mark of a movie, or the story will start to drag.

Let’s look at some examples:

The Wizard of Oz. At the 1/4 mark, Dorothy is taken, physically, to the Land of Oz. She can’t go back through the Doorway. There is no return. She has to make it through the rest of the plot, and survive, in order to go back.

The Fugitive has the train wreck and escape in the first act. Then Tommy Lee Jones and his team of trackers show up. He immediately figures out Kimble has escaped. He orders roadblocks and a complete area search. “Your fugitive’s name is Dr. Richard Kimble,” he says. “Go get him.”

That line is exactly one quarter of the way into the film. See what’s happened? All the essential elements of the story are in place: escaped man and his opponent. They have competing agendas. Death is on the line. If Kimble is caught, he’s toast. Death Row will be his final stop.

The first doorway can be an emotional push if it is strong enough to motivate the character into the death struggle.

That’s what happens in Star Wars. Luke’s Aunt Beru and Uncle Owen are murdered by Imperial stormtroopers searching for the droids C-3PO and R2-D2. Up to this point, Luke has only dreamed of going off on adventures. His loyalty to his aunt and uncle kept him on his home planet.

Now, though, he is experiencing loss and the desire to fight. He will go off with Obi-Wan Kenobi and learn the ways of the Jedi and join the rebellion.

Ask yourself this: When does your Lead character get forced—by an action or strong emotion, or both—into the main conflict of your story?

Be clear in your own mind, and on the page so the reader will have no doubt.

Then place that scene before the 20% mark of your word count.

Do those two things, and your novel will not feel like a drag!

***

This post is adapted from 27 Fiction Writing Blunders – And How Not To Make Them! (Compendium Press). The book is available now:

A new book! I’m dreadfully excited, just bought a Kindle edition, will comment when read more. Thanks!

Great advice as always! And the print version is out in the UK already. Excellent.

Just received word this morning that your new book is out. I’m adding it to my library and tool belt right now!

Jim,

I look forward to reading 27 BLUNDERS. Just bought it on Amazon. Thanks for bringing it out in print. I love to have my craft books in print.

Now writers can have 27 BLUNDERS sitting on their craft shelf beside Jack Bickam’s 38 MISTAKES.

Just wanted to pass on a compliment. I’m at a nonfiction mini conference in Orlando, Florida. I took the memoir track yesterday, taught by Larry Leech. When someone asked him about books to learn plotting, he immediately mentioned one book…and just one…PLOT AND STRUCTURE. When I told him later that I had an autographed copy, be was impressed. Those creative nonfiction writers need your book, too.

Thanks for your teaching!

Many thanks, all, for the kind support. I loved doing this book. It really is aimed at being a handy part of the writer’s “tool belt,” as Julie said.

@Steve: I met Larry years ago at a convention. Nice guy, knows his stuff. I’m grateful for the plug.

I just bought it, and am looking forward to reading it. I still refer to Plot & Structure when revising.

Thanks, Mike.

Beginner’s question: Do you ALWAYS needs this plot point, the doorway of no return?

Yes, I’ve read plot & structure, and superstructure, and I bought (but haven’t read yet) your blunders, but I’m in doubt.

Does it matter what kind of fiction we write? Does length matter? Genre?

The longer version of my question is: Is the number of plot points we need dependent of genre/length?

That is a GREAT question, Britt. Here’s the short answer: Yes, always needed, IF you want to write a story that readers relate to. The further you get away from structure, the harder it is for readers (because of how we’re wired for story). When you get very far away, you’re writing an experimental novel, which is perfectly fine. It just won’t sell many copies. But it’s your story, and you can do what you like.

But if you don’t get the Lead into the confrontation part of the novel by the 20% mark, it’s going to feel draggy to the vast majority of readers. And if the Lead isn’t “pushed” into Act II, the stakes aren’t high enough.

A story must begin, and it must end. And there must be a life & death struggle in the middle. That’s where 3 acts come from. That’s true for every genre. You can play with structure, you can experiment, you can ignore…and if you have a compelling style that may carry the book along for some readers. But I’m about helping writers take whatever their story is and making it relatable to a wide audience.

Again, that was a great question from a self-described “beginner.”

Keep writing.

Syd Field first introduced me to this concept but thanks to you for helping me go beyond the concept. You exposed the big lie and further explored how these pieces fit. And this piece is a major one. Thanks so much for sharing and the use of solid, popular examples.

Thanks, David. Field was the guy when I was in film school, and he really did set up structure studies. He wasn’t the only one, though. There was a guy at UCLA, a screenwriter from the “old days,” named Wells Root. I wrote about him here.

This is also known by the name of the Key Event. Good post and I’ll look up the Kindle version of your book. Looking foward to it.

Thanks Joe. The reason I call this the Doorway of no Return (rather than the “key event”) is that it gets across something crucial: once you’re through that door, there’s no going back. You have to fight through to the end.

If you COULD go back, it’s no a true plot point into Act II.

Singing to the choir here, Jim. Nicely done. I tell folks frequently that if you doubt this, or want to doubt it, test it. Go out there, read books, watch movies… that First Plot Point is always there, within arm’s reach of that targeted optimal location.

Right, Larry. And if it isn’t, you’ll know it. I remember watching a “thriller” and it started to drag…and I looked at the counter, and it was 35 minutes in. The film was not a hit.

Man, these math question keep getting harder and harder.

Thanks again, JSB. I look forward to reading this one. I’ve no doubt committed every blunder on your list. Cheers!

Thanks, Jim. The nice thing is we can survive the blunders. Unlike bomb demolition guys.

I fold over the corner of the pages 25% in, halfway looking for the mirror moment and 75% in for the beginning of the third act. I’ll check runtime of movies and watch for same. Rarely do events not unfold along this time frame.

As much as I abhor analyzing specific works of fiction, I’d love to understand the reason behind, why/how this structure sequence registers in the human mind and has since Aristotle. A little deeper look than, we’re born, live and die or we contemplate actions, take that action and live out the consequences of our choices. Something along these lines.

“Where does the power of fiction lie?

SB: The power of fiction is released, as I see it, by two processes. First, writers have to recruit or seduce or beguile us into their world – only then do we trust them to take us on this journey. The books we put down after only a few pages have failed to make that connection with us (and different writers, of course, connect with different people). Then there is the journey, and that’s where the power is most obvious. That’s where the reader and writer have made a compact, where a point of view is shared, where common responses are exploited.

TB: Until some neuroscientist cracks it, it’s an open question. We’re evolutionarily hardwired to look for patterns, for meaning; we crave narrative. This is a hindrance when unchecked but it’s also an incredible gift. Fiction brings you to places, emotionally and imaginatively, which you never otherwise would have visited. The psychologist Steven Pinker wondered once that, maybe, fiction is a kind of empathy technology. I like that. In its construction I think fiction is a skilled dreaming, and the story we construct in and from the dream is presented as a subtle thesis: given this set of people and this set of circumstances, this will happen. It’s a claim by the writer about the nature of some aspect of humanity, and that’s no small thing. The audacity of that is arresting; if you stick with me for the whole story, then it’s probably because you agree with me, you think, ‘Yeah, that’s how it is, you’ve told me the truth.’ And the truth is powerful.

MM: I suspect there are almost certainly as many answers to this question as there are people to answer it. My current favourite answer is the one given by Albert Camus in his book The Rebel [L’Homme revolté]. Camus says that all artwork is a demand for unity, a ‘reconciliation of the unique with the universal’, an imposition of order on our chaotic, closed and very limited experiences of the world. His core idea is that narrative art organises life in such a way that we can reflect on it from a distance, experience it anew and deny the transient nature of the everyday. Following Camus, I think fiction lets us press pause, rewind, zoom in, zoom out; it creates a space for us to think ourselves and our world in novel ways – to be titillated, frightened, disgusted, amused and surprised – often at ourselves – and meaningfully and distinctly from television or film, have significant control over that experience, to work with the author rather than be worked on by the author.

HT: Yes, I agree with Malachi and with Camus’s answer. Someone once said to me that it’s easy to recognise the people who don’t read fiction as their outlook on life is narrower and less imaginative, and they find it hard to put themselves in other people’s shoes. A generalisation, but with elements of truth. The power of fiction begins with fairy tales, nursery rhymes and picture books giving children ways of looking at the world and outside themselves. As we grow up, ‘the compact between reader and writer’, working with the author, is a powerful personal and shared experience, and in recent years a more public experience with the meteoric rise of book groups. The poet Billy Collins puts it well I think. On reading fiction he says: “I see all of us reading ourselves away from ourselves, straining in circles of light to find more light until the line of words becomes a trail of crumbs that we follow across a page of fresh snow…”

– See more at: http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/discussion/why-do-we-read-and-write-novels#sthash.yGuyYuyr.dpuf

mg, you need a government grant to study this out.

Let me try to score food stamps or some govt. cheese, first. baby steps you know

I’m gonna take MG’s suggestion and start tagging the respective 20-25% and 75% points and be more attentive in my reading.

Evaluating what I’m working thru now, I realize I’m at about the 40% mark with no “door” in sight~ but I’ll give the benefit of the doubt because it’s still somewhat interesting ~ not intriguing, but interesting.

On a parallel/side note, I may try a similar study of songs~ country music uses the three act structure a lot, but as I think about it, the best do tend to have a “door of no return” – late in the first verse or early in the second (and (+/- 25% of total word count ~ like Folsom Prison Blue? “I shot a man in Reno, Just to watch him die…” – Hard to walk back thru THAT door…)

Hmmm… Keep you posted~

🙂

g

Go for it, G.

Downloaded it yesterday and I’m already highlighting it 🙂