by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Gather ’round, children, and let me tell you a story about self-publishing back in the olden days.

Now, I know you kids think it’s always been easy. You just hit “upload” and … Johnny, put down that iPad! I’m telling you about real self-publishing, back when a writer had to have guts and grit! The days when self-publishing meant you paid for an honest-to-goodness print run and … Yes, Jenny? … no, print run was not a 5k. It meant shelling out money for printed, bound books made with pages made of actual paper! And let me tell you, that was not cheap! And at the end of it all, you know what you’d get? A bunch of boxes of unsold books in your garage!

You see, there has always been self-publishing in America. Thomas Paine, Mark Twain, and Walt Whitman dabbled in it. Heck, Whitman may have been the first sock puppet, writing a glowing anonymous “review” of Leaves of Grass and buying space for it in a literary journal.

But it was in the 1970s and a man named Bill Henderson that modern self-publishing went wide. Henderson’s The Publish-It-Yourself Handbook started a small but growing movement of ex-hippies and frustrated wannabes designing and printing their own work. (This is not to be confused with “vanity publishing,” wherein a company took a whole lot of money from you to produce a print run of books that would, well, remain in boxes in your garage.)

In 1979 Dan Poynter published the first of several editions of his Self-Publishing Manual, bringing a much-needed business sense to the movement.

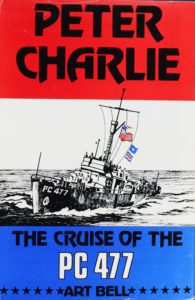

Which was around the time my dad, L.A. attorney Art Bell, decided to write a memoir of his service in World War II and publish it himself.

Raised in Hollywood, Dad was a star football and baseball player at Hollywood High School. He went on to play catcher for the UCLA baseball team, where his teammate was one Jackie Robinson.

In college he joined the Navy ROTC program and saw action throughout World War II. He was captain of three ships: the destroyers USS Dallas and USS Kinzer, and his first command and first love, the PC 477.

PCs were 173-foot, steel-hulled submarine fighters. Uncle Sam had thousands of seamen on hundreds of PCs convoying and patrolling in WWII. They were introduced in the desperate days of early 1942, when the waters off America’s Atlantic coast were a graveyard of torpedoed ships. They performed essential, hazardous, and sometimes spectacular missions, yet the PCs were scarcely known at all outside the service.

The Navy didn’t even dignify PCs with names. But the crew of the PC 477 did. They called her “Peter Charlie.”

Which became the title of Dad’s book. It was a true labor of love, and brought him back in contact with many of his shipmates. He collected letters and stories and photos, and organized a couple of reunions.

Dad was already self-publishing a digest on California search and seizure law, which had become the go-to resource in the state, so he had one of his graphics people do the layout of Peter Charlie, which he had typed himself on an IBM Selectric. He then paid a local printing outfit a princely sum for a beautiful hardback edition, with dust jacket and all. I can’t recall how many he had printed up. Maybe 2,000. He sold them himself out of his law office and it found popularity among many ex-Navy men all over the country.

Dad died in 1988 and I took over his practice. And I am proud to report that by 1999 or so, the entire print run had sold out. The book even returned a bit of a profit!

And that might have been the end of things were it not for the most recent iteration of the self-publishing movement: digital. I wanted Dad’s book to live on, and a few weeks ago I set out to make that happen.

First, I had to get the print text scanned. A writer friend recommended BlueLeaf Book Scanning. Per their instructions, I sent them one copy of the hardcover and chose their “destructive” option. That means they take the pages out of the binding for scanning, and you don’t get them back. The entire job cost $37.17. What I got were two Word docs (formatted and unformatted text), two PDFs (one large size, one small), and a JPEG of the dust jacket cover formatted for ebook use.

The scanning job was amazingly good. There was only one minor issue I found and took care of that with a quick find/replace.

Next, I opened up a Vellum project. Vellum is a Mac program for formatting ebooks (and, now, print as well). It is easy to use and creates gorgeous interiors. It will import a docx Word file and create most of the book that way. I went through the formatted Word doc and used cut-and-paste to put it into Vellum. Since there were a lot of block quotes and lists my dad used, this was the best way for me to check the transitions. Once again, Vellum makes the process easy.

I was also able to include photographs from the PDF scan. I copied the photos and saved them as JPEGs, then inserted them into the Vellum file.

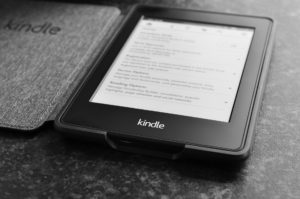

Once that was all done, I generated the .mobi file and sent that to my own Kindle so I could go over it on the device and pick up any last formatting issues. I fixed those in Vellum and generated the final .mobi that I used for publication under my imprint, Compendium Press.

Once that was all done, I generated the .mobi file and sent that to my own Kindle so I could go over it on the device and pick up any last formatting issues. I fixed those in Vellum and generated the final .mobi that I used for publication under my imprint, Compendium Press.

The entire project—from the time I shipped BlueLeaf the book to the official pub date—took six weeks.

And so Peter Charlie lives on. My hope is that those who had parents or grandparents who served in World War II and … yes, Billy? … Yes, we won … and anyone interested in a first-hand report of what life was like aboard a naval vessel at that time, will be both edified and educated by this account (I must add a slight language warning here, for the first captain of Peter Charlie was not averse to using God’s name to get the attention of his junior officers, Dad included). It is full of funny stories, historical data, some rare photos, and lots of interesting details.

It’s a Kindle Unlimited title, available here.

So … does anyone else remember the grand old days of self-publishing—before digital and print-on-demand? Anybody got a garage with boxes of unsolds?