Last time I wrote about suffering from what I call “revision block”, and discussed some possible solutions to this particular writing conundrum.

Writers can face a number of other mental challenges, to put it mildly. Today’s Words of Wisdom examines a trio of potential roadblocks, courtesy of three excerpts from the Kill Zone archives.

Clare Langley-Hawthorne considers how digital distractions can make you lose focus. Laura Benedict deals with a bane for many of us, procrastination. Sue Colletta discusses how “multi-tasking” can make writing harder.

All three excerpts are worth reading in full. Each excerpt is date-linked to its respective full version.

For writers, digital distractions are everywhere. At the moment my personal bugbear is my inability to wean myself off mindlessly checking the internet whenever I lose steam in my writing – the result? At least ten minutes of Daily Mail, Facebook and Gmail distraction resulting in – you guessed it, a complete loss of focus. Over the last week I’ve been paying greater attention to my writing habits (or lack thereof) and have realized that checking the internet has become a sort of ‘default’ setting whenever I’m stuck on a sentence or unsure of a passage of dialogue. I worry that my brain has lost the ability to focus for more than an hour at a time without craving some sort of distraction when the going gets tough. The answer to my problem is clearly weaning myself off the distraction itself but I’m surprised at how difficult this has become. I know I’m going to have to retrain my brain somehow as well as impose much stricter limits on succumbing to these distractions. My fear is that my ability to focus for long periods of time is already slipping away from me (can you hear the screams?…)

As readers, digital distractions allow ourselves to fulfill our craving for something new and more interesting whenever our focus wavers. Recently, I’ve found it is much harder to keep my focus on a book when my interest starts to wane. Whereas in the past I would plough on for a bit, hoping that a book would regain my interest, I now find myself turning to digital distractions much quicker than I ever would have put a book down before. It would be amazing to be able to create a safe room, look into options such as Soundproofexpert, and have that room as a digital hideaway, away from what ever distractions you may find on a day to day basis, or unfortunately even an hour to hour basis now.

I’m sure lack of focus has always been an issue for writers and readers, but I do feel that the increasing levels of digital ‘noise’ that surrounds us is making it much harder (at least for me) to keep the level of sharp focus I need on my writing. It certainly makes me less efficient and productive – although, thankfully, I still manage to pull off bursts of fear-induced focus which means I am completing my writing projects on time. I just feel that I need to develop techniques to sharpen my focus, increase my attention span, and spurn the digital ‘siren’ call that is all too easy to heed.

So what about you – do you find the digital world is making you lose focus? Have you developed strategies to overcome this while writing (or reading). Although disconnection is always an option for periods of time, it’s hard for this to be a permanent ‘default’ setting when so much of our world revolves around digital communications.

Clare Langley-Hawthorne—February 1, 2016

Even some of the most productive bestselling writers I know sometimes procrastinate. Personally, when I’m in my deepest procrastination moments, I forget that. It feels lonesome, and I become my own harshest judge. (That whole comparing oneself to other writers is deadly too, but we can consider that another time.) Being judgy while procrastinating is doubly unhelpful.

Procrastination offers an escape from tension. If I have a project (or chapter or paragraph or phone call or chore) that makes me feel anxious, I sometimes literally walk away from it. It might be for five minutes. It might be for an hour. It might be for weeks. Eventually I’ll return to it–or, if it’s some kind of chore or event–my lack of action will mean it expires and goes away.

Avoidance. It’s embarrassing to admit that I’m sometimes guilty of it. Ouch.

I’ve read many, many books to try to improve my productivity, shape my behavior, and, yes, fix my procrastination habit. Because it is a habit, not a disease or fatal flaw.

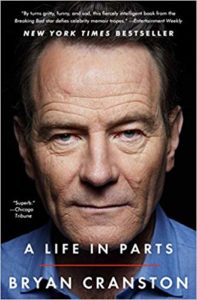

Here’s the latest book I’ve read on the subject:

I listened to it on audio via Overdrive and liked it well enough that I bought the ebook. (I often do that, anecdotal proof that library reads influence consumer book purchases.)

Notice that appealing subtitle. “A Strategic Program for Overcoming Procrastination and Enjoying Guilt-Free Play.” How sexy is that? I couldn’t resist checking it out when I was browsing available audiobooks. The subtitle worked on me exactly the way I’m sure it was intended: put the focus on the positive, not the procrastination.

KillZone is not the place for book reviews, but is about the writing life. So I’ll be brief.

THE NOW HABIT

- Helps you identify when and why you might be procrastinating.

- Doesn’t judge you for procrastinating–and even explains how it becomes an active coping tool.

- Doesn’t prioritize work over pleasure (a real revelation for me).

- Offers some compelling client stories.

- Has focus exercises and talks about the process and importance of flow.

- Helps you create your own “unschedule.”

- Has a good section about dealing with the procrastinators in your life.

- Explores goal setting.

The “unschedule” is my favorite piece of the process because it turns one’s schedule upside down. After blocking out the time you require for life’s necessities like eating, cleaning, sleeping, and tending dependent creatures, you mark out time for things that give you pleasure and put you in a state of play or creative play. Working out, practicing hobbies, spending time with friends. It might happen daily, weekly, or bi-weekly. Whatever you choose. It becomes a priority. A reward to work toward.

Work (or writing or publishing business for most of us here) can become more energizing. More efficient. I confess that on the days I’ve managed to put this into serious practice, I’ve found myself happily working overtime, sometimes working well into my scheduled pleasure time–but not feeling a bit deprived because I know I’ll get to play again soon. Also, I’m getting a huge amount of pleasure from my work hours.

Laura Benedict—July 11, 2018

Writers need to multitask. If you struggle with multitasking, don’t be too hard on yourself. The brain is not wired to complete more than one task at peak level. A recent study in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience showed when we’re concentrating on a task that involves sight, the brain will automatically decrease our hearing.

“The brain can’t cope with too many tasks: only one sense at a time can perform at its peak. This is why it’s not a good idea to talk on the phone while driving.” — Professor Jerker Rönnberg of Linköping University, who conducted the study.

The results of this study show that if we’re subjected to sound alone, the brain activity in the auditory cortex continues without any problems. But when the brain is given a visual task, such as writing, the response of the nerves in the auditory cortex decreases, and hearing becomes impaired.

As the difficulty of the task increases—like penning a novel—the nerves’ response to sound decreases even more. Which explains how some writers wear headphones while writing. The music becomes white noise.

For me, once I slide on the headphones, the world around me fades away. I can’t tell you the number of times my husband has strolled into my office, and I practically jump clean out of my skin. Don’t be surprised if someday he kills me by giving me a heart attack. But it isn’t really his fault, even though I’ll never tell him that. 😉 I’m in the zone, headphones on, music blaring, my complete attention on that screen, and apparently, my brain decreased my ability to hear.

Strangely enough, I don’t listen to music while researching. When I need to read and absorb content, I need silence. This quirk never made sense to me. Until now.

Have you ever turned down the radio while searching for a specific house number or highway exit? Instinctively, you’re helping your brain to concentrate on the visual task.

Research shows that our brains are not nearly as good at handling multiple tasks as we like to think they are. In fact, some researchers suggest multitasking can actually reduce productivity by as much as 40% (for everyone except Rev; he’s a multitasking God). Multitaskers have more trouble tuning out distractions than people who focus on one task at a time. Doing many different things at once can also impair cognitive ability.

Shocking, right?

Multitasking certainly isn’t a new concept, but the constant streams of information from numerous different sources do represent a relatively new problem. While we know that all this “noise” is not good for productivity, is it possible that it could also injure our brains?

Multitasking in the brain is managed by executive functions that control and manage cognitive processes and determine how, when, and in what order certain tasks are performed. According to Meyer, Evans, and Rubinstein, there are two stages to the executive control process.

- Goal shifting: Deciding to do one thing instead of another

- Role activation: Switching from the rules for the previous task to the rules for the new task (like writing vs. reading)

Moving through these steps may only add a few tenths of a second, but it can start to add up when people repeatedly switch back and forth. This might not be a big deal if you’re folding laundry and watching TV at the same time. However, where productivity is concerned, wasting even small amounts of time could be the difference between writing a novel in months vs. years.

Sue Coletta—July 12, 2021

***

- What’s your biggest digital distraction? How to you avoid it?

- Does procrastination hinder you in getting to the keyboard? If so, what gets you writing?

- Do you multitask when writing? How much of a hindrance or a help is that to your own process?

I know a demoralized writer. [Note: This is a composite portrait, though everything in it is fact based.] Said writer had written a number of good novels for a small house, then landed a two-book contract with one of the Big 5. The first book came out to mostly positive reviews, but not massive sales. The second book had to build on the first and make some serious money to justify the advance. The author worked really, really hard on this novel. It was in a popular genre, had a good title, and a great cover. The writer did all the right things marketing-wise, too.

I know a demoralized writer. [Note: This is a composite portrait, though everything in it is fact based.] Said writer had written a number of good novels for a small house, then landed a two-book contract with one of the Big 5. The first book came out to mostly positive reviews, but not massive sales. The second book had to build on the first and make some serious money to justify the advance. The author worked really, really hard on this novel. It was in a popular genre, had a good title, and a great cover. The writer did all the right things marketing-wise, too.