by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I’ve always liked the actor Bryan Cranston. He was my favorite secondary character on Seinfeld, playing WASP dentist Tim Whatley, who converts to Judaism so he can claim the rich history of Jewish jokes. (When Jerry objects, he is accused of being an anti-dentite.)

I’ve always liked the actor Bryan Cranston. He was my favorite secondary character on Seinfeld, playing WASP dentist Tim Whatley, who converts to Judaism so he can claim the rich history of Jewish jokes. (When Jerry objects, he is accused of being an anti-dentite.)

Cranston made regular TV appearances throughout the 90s, and spent seven seasons as the goofy father Hal in Malcolm in the Middle. Then came his signature role as Walter White, the high school chemistry teacher turned drug kingpin in Breaking Bad. Quite a jump for an actor known mostly for light comedy! But he was perfect casting in this binge-worthy descent into the heart of darkness.

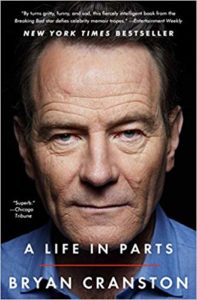

On a recent long drive I listened to Cranston’s autobiography, A Life in Parts. Read by the author, it’s an enjoyable account of Cranston’s rise as an actor. What’s clear from the book is that he takes his craft seriously. That’s why he went from bit-part support to respected lead—evidenced by four Emmys, a Golden Globe, a Tony (for playing Lyndon Johnson on Broadway), and an Oscar nod for his portrayal of the blacklisted writer Dalton Trumbo.

What made the book all the more interesting for me is that he and I are about the same age and grew up in the same place—the west San Fernando Valley. He went to Canoga Park High School; I went to nearby Taft. I was a young, struggling actor at the same time he was. We may even have crossed paths in Los Angeles at an audition for a commercial or TV show.

I really connected to that part of the book where Cranston describes the cold chill of auditions. How well I remember walking into waiting rooms with twenty other guys my age and look. Everybody sizing each other up. Then going into a room with a camera and a panel of unsmiling casting folk and reading the lines I’d been given. When I was finished, someone would say, “We’ll let you know.” I’d walk out, past the other actors, all trying to read my face as I attempted to hide what I was thinking: I blew it! Why did I say the line that way? I bet that meathead with the perfect chin gets it! What teeth whitener does he use?

Cranston covered this process with good humor and insight. But at one time the attendant anxieties were starting to debilitate him. So his wife, as a gift, purchased sessions with a life coach, who …

… suggested that I focus on process rather than on outcome. I wasn’t going to the audition to get anything: a job or money or validation. I wasn’t going to compete with the other guys. I was going to give something.

I wasn’t there to get a job. I was there to do a job. Simple as that. I was there to give a performance. If I attached to the outcome, I was setting myself up to expect, and thus to fail. My job was to focus on character. My job was to be interesting. My job was to be compelling. Take some chances. Serve the text. Enjoy the process.

And this wasn’t some semantic sleight-of-hand, it wasn’t some subtle form of barter or gamesmanship. There was to be no predicting or manipulating, no thinking of the outcome. Outcome was irrelevant. I couldn’t afford any longer to approach my work as a means to an end.

Once I made the switch, I was no longer a supplicant. I had power in any room I walked into. Which meant I could relax. I was free.

That, it seems to me, is perfect advice for a writer, too. Get rid of expectations! You can’t control outcome, only process. Keep your focus on the page in front of you. Connect with your characters. Tackle the challenges.

You’re not here to get something, you’re here to give something—entertainment value to a reader.

When your book comes out, as far as you are able (you’re human, after all) nix any expected outcome. Keep working on your next book and developing more projects. Sure, you go through the marketing routine and learn what you can. But don’t obsess about rankings and reviews. Forget the awards and the honors, which you can’t buy.

Just love your craft, the way Bryan Cranston loves his.

Then you will no longer be a supplicant. You will have power on the page. You’ll be free.

Where are you in the expectations game?