by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Carla Hoch

It’s my pleasure to introduce you to Carla Hoch, author of Fight Write: How to Write Believable Fight Scenes (Writer’s Digest Books). It’s a fantastic resource, jam-packed with info, tips, and techniques on virtually every aspect of physical altercations. As such it is useful both as a resource (to make sure you know what you’re writing about) and a brainstorming tool (providing abundant ideas for making your fight scenes vivid and original). It’s also a pleasure to read in Carla’s jaunty, entertaining voice. Carla is a writer herself and a trained fighter with experience in nearly one dozen martial arts and fighting styles. Settle in, this is a lengthy interview, but entirely worth your time. Without further fondue:

One of the great benefits of your book is as a reference when planning a fight scene. With all the possibilities of strikes, moves, weapons, size disparities of the opponents and so on, one can create an almost infinite variety of fight scenes, just as there is almost an infinite variety of chess moves, right?

Absolutely, and the proficiency of the fighter isn’t just in how many different techniques they know but also in their ability to combine them productively. A fighter can know a hundred moves, but if the fighter can’t combine them, they are basically knowledge rich but skill poor.

You advocate working backwards, starting with the type of injury you want to have at the end of the fight scene. Then choreographing the scene by actually moving around physically and doing the strikes yourself. This is best done privately and not at Starbucks, I assume. Can you expand on this?

If you walk through your fight scene in Starbucks, do it before you give them your name for your order. Or, use a different name, like, I don’t know, Jim Bell.

Every writer has their own process. But, I, as a writer and fighter, highly suggest blocking your fight around the injury goal. For one, starting with the injury in mind gives you a destination, and it’s much easier to get somewhere if you know where you should end up. Having an injury goal also keeps the story front and center. Whatever harm you mean to inflict in the scene has to further the plot or bring the reader into the story. So, basing movements around that harm ensures that you will have the wound your plot or character development requires. I teach a whole class on injuries and what they offer your story. They can really be great tools.

The injury goal also determines the movement. A character who aims to break someone’s nose will move differently than a character who means to hobble someone. Also, if you want the injury to be mild, that immediately negates certain weaponry and moves. If I need the character to die, then I know I need to create a scenario where that could happen.

I really do suggest moving around and doing a bit of the blocking to know how your character’s body will be oriented. This is especially important if you have no fight training. And, don’t worry, you don’t have to be able to do the moves as well as your character can. But move around to see if the moves you are linking can actually connect.

As you move, think about how the actions impact each fighter not only offensively but defensively. Let’s say your character is being struck under the chin with an upper cut. If you were punched under your chin with straight, upward momentum, what would your head do? It would kick backward. So, if that strike knocked you out, in what direction would you likely fall? Look straight up as far as you can and see how your body moves. You’ll notice that your whole body tilts backward. Knocked out, you’d likely fall onto your back. If your character needs to fall forward, you now know, because you moved your body, that an upper cut isn’t the punch to accomplish that.

Bodily response is a part of fight strategy. Fighters do certain techniques in order to get certain responses from their opponent. For example, if I’m boxing and want to punch my opponent’s jaw but they are guarding their face well, I will punch at their midsection. If I make contact with the abdomen, great, but I don’t have to. What I want is for my opponent to drop their hands to guard their midsection, thereby exposing their jaw, or crunch their abs which brings their head down. Even if I can’t make contact with their jaw, with their head down their temples are likely accessible and temples are good targets too.

On that note, don’t be too fancy. Really and truly, readers want to know the implications of the moves far more than the moves themselves. Readers want a sensory experience. It’s what they can relate to! Not every knows what it’s like to punch or be punched in the eye. But everyone has gotten something in their eye. They know that when one eye hurts, the other eye squints and waters and you can’t see and then your nose gets runny and you sniffle and snort and even though it’s just dust in your eye everything comes to a screeching halt until the invasive speck is out of your eye!!! It’s maddening! Use that common, maddening experience.

How about using a blank piece of paper and drawing the scene?

If that works for you, I think that is great! It’s definitely helpful if there are a lot of people involved or if the battle scene is epic and involves troop formation.

One usually thinks of the size advantage, as in a Jack Reacher type. But you point out some of the advantages of a smaller fighter. What are those?

Well, first, the advantages are few and far between. I know this from experience. And you may hear people say that technique beats size and strength so as long as your smaller fighter is highly trained, they are fine. Let me tell ya something. Go ahead and scoot in close and let me whisper this so I don’t offend anyone who believes that lie. The only people who say technique always beats size and strength are either big or haven’t fought a day in their life!

What smaller people have to their advantage is that they are used to the size disparity and have learned to work with it. They know what they need to do to strike someone taller because it’s a problem they face often. It is also easier for smaller people to slip out of holds by larger people. My jiujitsu coach is very muscular. When he bends his arm, his bicep hits his forearm and, let me tell ya, I’m so thankful for that. Above his bicep is a little bit of space that I can use to wiggle my hand in to use as a brace. Another one of my coaches in very tall. His long limbs have a problem keeping a tight hold on me.

What smaller people have to their advantage is that they are used to the size disparity and have learned to work with it. They know what they need to do to strike someone taller because it’s a problem they face often. It is also easier for smaller people to slip out of holds by larger people. My jiujitsu coach is very muscular. When he bends his arm, his bicep hits his forearm and, let me tell ya, I’m so thankful for that. Above his bicep is a little bit of space that I can use to wiggle my hand in to use as a brace. Another one of my coaches in very tall. His long limbs have a problem keeping a tight hold on me.

Physics is also on the side of the smaller person. They have a greater potential for rotation and can change their momentum more quickly than a larger person for the simple fact they have less mass. That’s one reason why gymnasts tend to be small. However, that doesn’t mean a larger person can’t be as agile or quick as a smaller person.

As a whole, however, smaller people are at a disadvantage. They have less mass which means that to create as much force in their strike as a larger person, they have to be exceptionally fast. That is one reason why combat sports have weight divisions. Larger opponents also tend to have more muscle mass. More muscle means more strength and a heavier frame. All that can be used against a smaller fighter. I have literally had larger teammates stand up with me hanging off of them still fighting as best I can. In class it’s funny. In a street fight that is death. The reason I am able to best larger opponents in combat sports is because my opponents are willing to abide by the rules of that sport and not simply pick me up and throw me or squash me like a bug.

What are some fight clichés you see over and over?

The Darth Vader hold: picking up someone by their neck. Y’all, you just can’t do that. First, the human spine isn’t meant to support the body’s weight by the cervical vertebrae at the head. That’s why hanging is a “thing.” Also, if you were held like that, the grip would be such that you couldn’t talk as so many characters in that position do. Lastly, holding that weight with one arm, especially a straight arm, would take Herculean strength and even if you had it, that much weight out in front of you would make you topple forward.

Another cliché that I see is using two swords at once. I did a little Filipino Martial Arts and it has a two-sword style known as Estilo Macabebe. I’ve written about it on my blog but have never done it. Pretty sure I’d cut my own head off immediately. I don’t have issue with a character having that style. The problem I have is why they have that style. Estilo Macabebe began with a particular purpose. Your character’s fighting style should also have a purpose that fits them and the setting of the work. They can’t just have a two-blade style because it’s showy and cool. Trust me, trained fighters are not showy. They want maximum efficiency with minimal effort. If they go to the trouble of using two swords, there’s a reason. And, yes, one of those reasons might be intimidation to hopefully avoid conflict. So, even when a fighter happens to fight fancy, there’s a purpose that goes far beyond just being cool.

That said, two-blade styles are so cool and I wish I knew one!

In all the old Westerns, fights are almost exclusively punches to the face, back and forth. Isn’t a fist to someone’s face like hitting a brick? How do you punch a guy’s jaw without ruining your hand?

Hitting someone with bare knuckles leaves the hand open to major damage. Fighters in striking sports don’t wear gloves to protect their opponent’s face. They wear them to protect their own hands. And, under those gloves is tight wrapping to pull the bones of the hand together and further protect them from breaking. Breaking the bones of the hands by punching is so common that a fracture of the bones under the ring and pinkie fingers are called “boxer’s breaks.” The bones of the hand are not created to support the impact of punching. Our moms were right. Hands weren’t made for hitting.

All that said, people punch other people in the face all the time. If they don’t suffer a boxer’s break from the punch they are either lucky, much bigger than the target of the punch or have a job that has made the bones of their hands thicker. The best way to punch and not break the bones of the hand is not to punch at all. I know, I hate that answer too. It’s like when I ask my jiujitsu coach how to get out of something and his reply his, “don’t get in that position.”

When I teach self-defense, I suggest using hammer fists, defensive slaps and palm strikes. A hammer fist is a downward strike with a fist. It’s the same motion as hammering, thus, the name. If you are striking downward, hammer fist is the way to go. A defensive slap is a slap delivered with a cupped hand. You get your whole body into it like a punch. And don’t let the “slap” part mislead you. Defensive slaps are used in combat sports and will knock you out. They can also rupture an ear drum. They are great to use if you have sideways momentum. A palm strike is great for straight strikes that go directly in front of you or upward. You make contact with the base of your palm. Palm strikes can break a nose, bust lips and severely damage an eye.

And if your character gets a Tyson-like punch in the face, what’s that going to feel like?

If Iron Mike punched your character in the face they wouldn’t feel a thing. They’d be dead. Seriously. The force of Tyson’s punch is about a ton per square inch. It would break the average person’s neck. Fighters don’t just train to deliver punches. They train to take them. They strengthen their necks and learn to move with a punch to lessen the force of it.

You suggest that the winner of a fight carries around some physical and psychological trauma afterward. It seems to me some of that needs to be depicted and makes the whole thing more realistic. Tell us more.

Hurting people hurts. Period. Physically, beating someone up can leave your muscles sore and beat up your hands. Light swords grow heavy after a while. Even shooting for long periods of time can make your body ache.

Harming another is also damaging to the psyche. The closer an assailant is to the person they assault/kill, the higher the incidence of PTSD, especially if they see the victim’s face. And, yes, bad guys get PTSD. They just don’t talk about it. But, if you watch interviews with murderers, you will hear them say that they have nightmares about the person(s) they killed. Or you may notice that they are completely numb, not registering any emotion in connection to their actions. The latter is a much unhealthier state because they are not allowing their mind to deal with what they have done.

Those whose job may require them to harm another go through training that primes their brain to do so. I go through several aspects of this sort of training in my book. Some of the most common techniques are firing upon targets with a human form and referring to people with words that don’t call to mind their humanity. This is why you will hear policemen or soldiers use words like “perp”, “suspect,” “insurgent,” “assailant.” They aren’t using those words because they don’t value people. Policemen and soldiers do their job because they do value people. They use these words because they are trained to use those words, and they are trained to use those words in the case they must kill that person to save another. It is more palpable to the brain to “dispatch a target,” than “kill a human.” But, even with mental training, the mind suffers. The term PTSD came directly from work with Vietnam Vets.

Explain what JACA stands for.

JACA is a matrix used by threat assessment specialists to determine whether a threat made is credible. It was coined by Gavin deBecker, writer of the book The Gift of Fear. Everyone should read that book!

JACA is an acronym that helps predict violence. When a person makes a threat, you have to ask if that person has:

Justification – Does the person have justification for their threatened action? Were they jilted, fired, humiliated? Do they have what they see as a legitimate reason to do what they are threatening to do?

Alternatives – Does the person see alternatives to their proposed violence? In other words, does the person legitimately see no other way to handle the situation other than violence.

Consequences – Does the person see the risk of violence as worth the reward? Do they care about what could happen to them as a result?

Ability – Is the person able to carry out the threat? Are they close enough in proximity? Do they have the weaponry or physical skillset?

We have a plethora today in the movies of females kicking butt. Unless it’s a superhero, how can we bring more realism when it’s a woman doing the fighting?

Good question. Pardon me while I assemble my soap box. (hammering, hammering) Ok, here we go. Ahem! First, if your character is a trained fighter, she will fight no differently than a man. Fighters base their game on their body type and natural abilities not their gender. I have trained in ten fighting styles in as many years. Not once has a coach/sensei separated the class to teach gender specific techniques. Techniques are based in science, usually physics, and science isn’t sexist.

Also, a female in combat will dress like a male in combat. In other words, their armor doesn’t show their mid-drift! They don’t wear a helmet, carry a shield and wear a leather bikini. I mean, what is that?

Tell us a little bit about gaslighting as a weapon.

Gaslighting is a form of mental manipulation. It is an attempt to gain power over another person by causing them to question reality. When a person isn’t sure what is real, they have no concept of the amount of control another person has over them. It’s a common tactic of narcissists, cult leaders, dictators and my cat Dottie. Everything out of that one’s mouth is just straight up lies and manipulation.

One of the tactics of gaslighters is illusory truth. They will say something so often that others come to believe it. They will tell flagrant lies with such conviction that you will question whether you should even question them. They deny having said things even when there is proof. When backed into a corner they will deflect and tell you that you are being crazy or too sensitive.

Gaslighters thrive on confusion and amass troops, or at least make you believe they are, to “prove to you” that you are wrong. “Everybody knows how you are.” “Everyone says you’re too sensitive.” They also project and accuse you of what they are guilty of. “You are cheating on me and I know it.” “You lie all the time. Your friends told me so.” Above all, they will voraciously deny that they are gaslighters.

Victims of gaslighting often question themselves. After an interaction with the gaslighter they feel confused or crazy. They constantly apologize to the gaslighter. They feel hopeless and joyless and can’t understand why, with all that is good in their life, they feel that way. They lie to avoid put-downs from the gaslighter. They have trouble making decisions.

I cannot stress the amount of damage a gaslighter can do. It’s diabolical.

You write in your book about “the science of being knocked out.” What do writers miss?

First, I think people believe being knocked unconscious is always the result of a concussion. Sustaining a concussion from a punch can make you lose consciousness, but just because you lost consciousness doesn’t automatically mean you have a concussion. Honestly, I think more concussions happen when the person collapses and hits the floor.

Any time the body sustains a blow hard enough to disrupt blood, it can temporarily lose consciousness. It is the body’s effort to get the brain even with the heart to maximize blood flow. And, unless you can float, to get the head and chest on the same plain, you will have to lie down.

When a person goes unconscious from a punch or from being “choked out,” they don’t stay that way for long unless they do have a fair amount of brain damage. Now, I have never left a teammate unconscious to see how long it took them to come to, but I’ve been told that, left unassisted, they will likely be out for maybe ten seconds. Again, that is barring brain damage.

One of the creepiest things I see when people are knocked out, and that people who’ve never seen it don’t know, is that while unconscious people will jerk, wiggle and sometimes hiss. It honestly looks like they might be dying. Their limbs will go stiff, their toes will curl and that is all because of the body trying to “reboot” itself. Nerves are firing like crazy.

Also, when a person regains consciousness, they tend to come back to the moment before they were knocked/choked out. So, they may come to throwing punches! My jiujitsu coach was choked out a few weeks ago. I ran over to him and lifted his feet to get more blood flow to the brain – that’s what you should do. When he regained consciousness, after maybe five seconds, he immediately reached out as if in the middle of the fight. When he saw me standing above him, he asked what happened. I told him that I had had choked him out. (I hadn’t. I was tricking him. I regret nothing.) I could see him mulling it over and looking around. Finally, the moment before he blacked out returned to his mind and he looked at the guy who had bested him. Everyone laughed. But, to this day, I gaslight him and assure him that I was the one to choke him out. (Again, I regret nothing.)

Where can we find you on the internet?

My main presence is on my site, FightWrite.net. It has been listed in Writer’s Digest top sites for writers four years in a row and has won two Gold Crown Awards with CAN for media presence. There you can read my blog, going strong since 2016, buy my book, reach out to me or take a class.

I am active on Instagram and IGTV @fightwritecarla. I give lots of fight scene tips and post regular reader engagement posts. Like, today, I asked, “What move is actually better than the book?” I have some videos on IGTV as well. I have a regular post on the Writer’s Digest Blog and I also have videos on YouTube.

Thank you, Carla, for being our guest today.

No, thank YOU!

***

Carla has a busy morning, but may be able to drop by later. Comments are open!

Brother Gilstrap’s recent post on critique groups raises a question I’ve heard from other writers: When do I know my book is ready to go out to an agent, editor, or direct to market?

Brother Gilstrap’s recent post on critique groups raises a question I’ve heard from other writers: When do I know my book is ready to go out to an agent, editor, or direct to market?

Whenever I think of the past, it brings back so many memories. – Steven Wright

Whenever I think of the past, it brings back so many memories. – Steven Wright A question I’m asked from time to time is about whether or not an author can quote a song lyric in a novel.

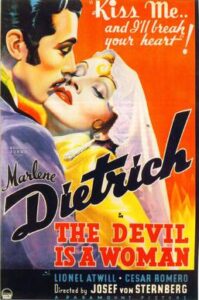

A question I’m asked from time to time is about whether or not an author can quote a song lyric in a novel. Today I begin an occasional feature—JSB at the Movies. I’m a lifelong movie fan, my B.A. is in Film Studies, and I often use movie clips in my craft workshops. The crossover between screen and page storytelling is substantial.

Today I begin an occasional feature—JSB at the Movies. I’m a lifelong movie fan, my B.A. is in Film Studies, and I often use movie clips in my craft workshops. The crossover between screen and page storytelling is substantial. Wonderful Life begins and ends on the same Christmas Eve, in a town called Bedford Falls. It opens with shots of the snowy town, and the voices of various townspeople praying for a man named George Bailey. The last voice is the one we’ll come to know as Zuzu (George’s youngest child) pleading, “Please bring Daddy back!”

Wonderful Life begins and ends on the same Christmas Eve, in a town called Bedford Falls. It opens with shots of the snowy town, and the voices of various townspeople praying for a man named George Bailey. The last voice is the one we’ll come to know as Zuzu (George’s youngest child) pleading, “Please bring Daddy back!” George Bailey (James Stewart) is a good man, a solid citizen, but is far from perfect. He’s not above leering at the attractive derrière of Violet Bick (Gloria Grahame) as she shimmies down the street. He loses his temper and becomes abusive. He verbally destroys the simple-minded Uncle Billy when the latter loses a crucial bank deposit. On Christmas Eve, his life at its lowest ebb, he screams over the phone at his child’s teacher, then yells at his children, bringing them to tears. (Stewart’s acting is brilliant throughout. He was suitably nominated for Best Actor, losing only because the equally brilliant Frederic March in The Best Years of Our Lives.)

George Bailey (James Stewart) is a good man, a solid citizen, but is far from perfect. He’s not above leering at the attractive derrière of Violet Bick (Gloria Grahame) as she shimmies down the street. He loses his temper and becomes abusive. He verbally destroys the simple-minded Uncle Billy when the latter loses a crucial bank deposit. On Christmas Eve, his life at its lowest ebb, he screams over the phone at his child’s teacher, then yells at his children, bringing them to tears. (Stewart’s acting is brilliant throughout. He was suitably nominated for Best Actor, losing only because the equally brilliant Frederic March in The Best Years of Our Lives.) Every one of the secondary characters in Wonderful Life is well-drawn and engaging in their own right. Clarence the Angel (Henry Travers); Bert the cop (Ward Bond); Ernie the cab driver (Frank Faylen); the tragic Mr. Gower (H. B. Warner); all the way down to Zuzu (Karolyn Grimes, who is still with us). Old Man Potter (Lionel Barrymore) is a classic villain, and even his nonspeaking servant has an eerie presence.

Every one of the secondary characters in Wonderful Life is well-drawn and engaging in their own right. Clarence the Angel (Henry Travers); Bert the cop (Ward Bond); Ernie the cab driver (Frank Faylen); the tragic Mr. Gower (H. B. Warner); all the way down to Zuzu (Karolyn Grimes, who is still with us). Old Man Potter (Lionel Barrymore) is a classic villain, and even his nonspeaking servant has an eerie presence. Which doesn’t help George’s frustration about staying in town. That evening he finds himself walking by Mary Hatch’s house. Mary, back in town from school, has been waiting for this moment. She has on her best dress and has set up the parlor to reveal a picture of a romantic moment from their high school days—when George said he would “lasso the moon” for Mary.

Which doesn’t help George’s frustration about staying in town. That evening he finds himself walking by Mary Hatch’s house. Mary, back in town from school, has been waiting for this moment. She has on her best dress and has set up the parlor to reveal a picture of a romantic moment from their high school days—when George said he would “lasso the moon” for Mary. “You wouldn’t mind living in the nicest house in town,” Potter says, “buying your wife a lot of fine clothes, a couple of business trips to New York a year, maybe once in a while Europe. You wouldn’t mind that, would you, George?”

“You wouldn’t mind living in the nicest house in town,” Potter says, “buying your wife a lot of fine clothes, a couple of business trips to New York a year, maybe once in a while Europe. You wouldn’t mind that, would you, George?” In Wonderful Life, George’s realization about his town’s love is argued against in Act 1. That’s when the young George Bailey tells the two girls, Mary and Violet, the following:

In Wonderful Life, George’s realization about his town’s love is argued against in Act 1. That’s when the young George Bailey tells the two girls, Mary and Violet, the following:

The other morning, as is my wont (and I want what I wont when I want it) I took a fresh cup of joe and my AlphaSmart to the backyard for some thinking, pondering, and writing time. The joe was brewed in my moka pot, a gift to mankind from the Italian inventor Alfonso Bialetti. Usually I take it black, but we happened to have some Coffeemate Sweet Italian Cream in the fridge. I thought the key word was Italian, but as it turns out the emphasis should be on sweet. This stuff is a sugar bomb. You need less than a dollop of regular cream. My hand trembled, and I poured in a touch too much.

The other morning, as is my wont (and I want what I wont when I want it) I took a fresh cup of joe and my AlphaSmart to the backyard for some thinking, pondering, and writing time. The joe was brewed in my moka pot, a gift to mankind from the Italian inventor Alfonso Bialetti. Usually I take it black, but we happened to have some Coffeemate Sweet Italian Cream in the fridge. I thought the key word was Italian, but as it turns out the emphasis should be on sweet. This stuff is a sugar bomb. You need less than a dollop of regular cream. My hand trembled, and I poured in a touch too much.

What author, past or present, would you most like (or have liked) to have dinner with? You get to pick the meal. What would you select?

What author, past or present, would you most like (or have liked) to have dinner with? You get to pick the meal. What would you select?