by Jodie Renner, editor, author, presenter

by Jodie Renner, editor, author, presenter

As a freelance editor, I receive fiction manuscripts from lots of professionals, and for many of these clients, whose report-writing skills are well-researched, accurate and precise, my editing often focuses on helping them relax their overly correct writing style.

Writing fiction that sizzles is a world away from nonfiction writing, especially scholarly, professional, or technical copy. In fact, people who have had a lot of experience writing academic, professional, legal, or business documents often have the steepest learning curve when it comes to switching to fiction. Professionals typically have the most “bad” (correct but inappropriate for fiction) habits to unlearn when they’re trying to create a believable story world with a casual, even quirky voice; lively, fast-paced writing; and colorful characters from various walks of life.

Here are some concrete tips for relaxing your writing style, trimming the clutter, and finding an authentic, appealing voice for your story, whether you’re a professional or not. Most of this advice also applies to writing engaging, zippy, natural-sounding blog posts.

~ To loosen up, read lots of popular fiction – and blog posts.

An excellent first step to counteract stiff, overly correct, nonfiction-type writing habits is to read a lot of bestselling fiction in the genre you want to write. Even better, try reading the novels aloud, or buy the audio books and listen to them in your car, on walks, or while puttering around the house or garage. You’ll soon get into the rhythm of the writing and start to develop your own natural, compelling fiction voice.

~ Relax and pare down any overly correct, convoluted sentences.

Remember, it’s about communicating images and concepts and carrying your reader along with the story. Don’t muddle your message with a lot of extra words that just clutter up the sentence and hamper the free flow of ideas.

Here are some well-disguised examples from my fiction editing of trimming excess words:

Before:

“Bastards. Why am I always the last to know?” Pivoting, the detective walked in the direction of the station’s front desk with a purposeful, nearly aggressive, gait. He shoved himself bodily through the swinging door and locked eye contact with the uniformed officer on reception duty.

Notice how the ideas flow better in the revised version:

After:

“Bastards. Why am I always the last to know?” Pivoting, the detective marched toward the front desk. He slammed through the swinging door and glared at the officer on reception duty.

Before:

Nathan paused a moment before replying as he slowed the car in preparation for a right-hand turn onto a smaller road, resuming the conversation as the car again picked up speed.

After:

Nathan paused as he slowed the car to turn right onto a smaller road, then continued as the car picked up speed.

~ Don’t drown your readers in details.

Too much unnecessary detail complicates the issue and impedes the flow of ideas.

Leave out those picky little details that just serve to distract the reader, who wonders for an instant why they’re there and if they’re significant:

Before:

He had arrived at the vending machine and was punching the buttons on its front with an outstretched index finger when a voice from behind him broke him away from his thoughts.

After:

He was punching the buttons on the vending machine when a voice behind him broke into his thoughts.

In the first example, we have way too much minute detail. What else would he be punching the buttons with besides his finger? And we don’t need to know which finger or that it’s outstretched. Everybody does it pretty much the same. Avoid having minute details like this that just clutter up your prose.

Before:

The officer was indicating with a hand gesture a door that was behind and off to the right of Wilson. An angular snarl stuck to his face, he swung his head around to look in the direction the officer was pointing.

After:

The officer gestured to a door behind Wilson. Snarling, he turned to look behind him.

Before:

Jason motioned to a particular number in the middle of the spreadsheet that Tom currently had on the computer screen.

After:

Jason motioned to a number in the middle of the spreadsheet on the screen.

Or:

Jason pointed to a number in the middle of the spreadsheet.

Or even better:

Jason pointed to a number on the spreadsheet.

~ Condense long-winded dialogue and make sure it reflects the speaker’s personality and background.

People rarely speak in complete, grammatically correct sentences, especially when they’re in a casual situation, in a hurry, or angry, upset or scared. Overly correct dialogue just doesn’t sound natural. Unless you’ve got two professors or other professionals speaking to each other in the workplace, don’t have your characters speaking in long sentences in lengthy paragraphs.

In tense or rushed action scenes especially, go for incomplete sentences and one or two-word questions and answers. Read your dialogue aloud or even role-play with a friend to hear where you can cut words to make it sound more realistic.

Before:

The homicide detective looked at the CSI, who was on his way out. “Leaving already?”

“This wasn’t the crime scene. Not much for me to find. You would do me a huge favor by making sure that the next time we had a murder I had an actual crime scene to investigate.”

“I’ll keep that in mind.”

After:

The homicide detective looked at the CSI, who was on his way out. “Leaving already?”

“This wasn’t the crime scene. Not much for me to find. Next time can you get me an actual crime scene to investigate?”

“I’ll keep that in mind.”

Before:

“C’mon, I don’t believe that. Lance knew you’d tell the cops about the connection. He just wanted the excuse in place because he knew Perkins might not be leaving.”

After:

“C’mon, I don’t believe that. Lance knew you’d tell the cops about the connection. He just wanted an excuse in case Perkins didn’t leave.”

Before:

Craig flipped a page in his notebook. “Do you keep records in your system that specify which of your inmates have had access to this room?”

After:

Craig flipped a page in his notebook. “Do you keep records of patients who’ve had access to this room?”

So be sure to read or listen to lots of fiction, and read your story out loud to see if it sounds natural, like people in those situations would actually talk and think. And delete all those extra little words that are cluttering up your prose, to create a smooth, natural flow of ideas.

For more on this topic, see my blog post, “Making the switch from Nonfiction to Fiction Writing,” on Joanna Penn’s award-winning blog.

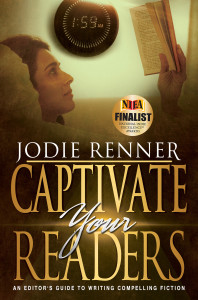

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft- of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources to date: Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage. You can find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, her blog, http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/, and on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.

of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources to date: Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage. You can find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, her blog, http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/, and on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.