by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

My research tells me it’s Mother’s Day. So: Happy Mother’s Day! As Casey Stengel used to say, “You could look it up.”

But before the internet, it was rather easy for a writer to “fake it” when it came to research. That’s because a) there wasn’t an easy way for a reader to find, instantly, whether a detail was correct or not; and b) there wasn’t any social media or customer reviews for blowback. Thus, an author could get away with a bit of sloppiness—if that’s the kind of writer he wanted to be.

I have a friend who is an accomplished historical fiction writer. He worked his tail off on a series that came out in the early 90s. His research was impeccable. While his series sold okay, another historical fiction writer was enjoying much greater success with his series which (to put it mildly) was rather deficient in the research arena. Indeed, I read one of the books in preparation for my own historical series. This author’s book took place in 1904, but after a couple of chapters I had to put it down, because he had a thriving silent movie industry happening in Hollywood.

One problem: Hollywood did not become a popular movie location until around 1910, and certainly wasn’t hopping until the teens.

These days, you couldn’t get away with such a mistake. But would you want to?

Some significant fakery occurs in the classic film, Casablanca. One of the screenwriters, Julius Epstein, once admitted:

There never were Letters of Transit. Germans never wore uniforms in Casablanca, that was part of the Vichy agreement. But we didn’t know what was going on in Casablanca. We didn’t even know where Casablanca was!

But Letters of Transit sounds real. Which is, of course, the key to fakery!

In the 1960s Lawrence Block wrote a paperback series about a world-roaming secret agent named Tanner. When he got the galleys for one of the books he saw an odd term in the text: tobbo shop. What? He checked his own manuscript and saw that he had written tobacco shop. The typesetter had made a mistake. But Block sat back and mused that tobbo shop had a realistic ring to it and besides, how many readers would have been to Bangkok? (I believe he even got some letters from readers who had been there, and did remember those “quaint tobbo shops.”)

Harlan Coben issues a warning about research:

“I think it’s actually a negative for writers sometimes when they’re writing contemporary novels to know too much. First of all, doing research is more fun than writing, so you start getting into the research and you forget to tell your story. And, second, which is on a very parallel track … sometimes you learn all kinds of cute factoids you think are so interesting that you include them in the book, but you weigh the story down. I try not to do that.”

One method I’ve used when writing hot (and not wanting to stop) and I get to a spot where I know I’ll need research, I’ll put in a placeholder (***) and keep writing. I’ll make my best guess about how the scene should go, then do any additions or corrections later.

On the other hand, when writing historical fiction, which demands detail precision, I have to do a lot of research up front. For my series about a young woman lawyer in turn-of-the-century Los Angeles, I spent many, many hours in the downtown L.A. library, poring over microfilm of the newspapers of the day. I have two huge binders full of this research, and I’m really proud of the results. But man, it’s hard work (am I right, Clare?)

But it’s worth it. When the first book came out almost twenty years ago it sold great and got uniformly positive reviews, several mentioning the historical accuracy. I did, however, get a physical letter (remember those?) from the curator of a telephone museum! He said he enjoyed the book, but there was one little detail about my lead, Kit Shannon, using a wall telephone, that I got wrong. The one guy in the United States who would have noticed this happened to read my book!

Naturally, it was not plausible to dump all the books in the warehouse to change that teeny, tiny thing. And who else was going to notice? But it rankled me, nonetheless.

When I got the rights back to the series, that was the only thing I wanted to change. All those years later I was still mad about it! Unfortunately, I couldn’t find the letter from the museum guy. I decided to try to find him online. Instead I found another museum and emailed somebody there, explaining the detail. In return, I got a nice email back telling me there was a model of telephone that operated exactly like I had it. It would have been used only by very wealthy people.

Which is how it was in my book. Kit lives with her wealthy great aunt in the posh section of town known as Angeleno Heights.

I’d been right all along! How about them apples? (Yes, I’ve been wrong before. It was in October of 1993. I thought the Phillies would win the World Series.)

Today, there are areas in your fiction that you’d better get right or you’ll hear about it, boy howdy. Perhaps the biggest of these is weapons. If you have your hero cocking the hammer of his Glock, expect a flood of abuse letting you know that a Glock has no hammer. (And if Gilstrap reads your book, duck, because he’ll be throwing it at you.) If you have your hero shoving another clip into his Beretta, you’ll have an irate horde telling you to shove … never mind, just note that a clip is not a magazine.

If you’re not accurate about a place, you’ll hear from people who live there. This is partly why I base most of my books in my hometown of Los Angeles. I grew up here. I know it. That it also happens to be the greatest crime-noir city is a bonus.

But sometimes I want to venture forth. In some instances, to save me from a cumbersome research trip, I simply make up a town and slap it down somewhere. If people want to take the time to look it up and find out it doesn’t exist, they’ll know I made it up and accept it. Ross Macdonald and Sue Grafton set their series in Santa Teresa, a stand-in for Santa Barbara that allowed them plenty of leeway to make up locations within. No one’s complaining.

So I’ll throw it open. What’s your philosophy on research? Do you follow rabbit trails that can be an excuse to not write? Do you like to do as much….or as little… as possible? Do you, when the spirit moves, “fake it”?

***

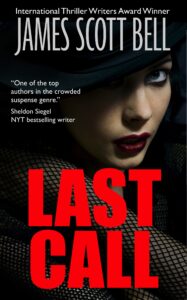

Reminder: My latest stand-alone thriller, LAST CALL, is still available at the launch price of 99¢. Because I want you to have it. Enjoy!

You’ve just been abducted.

You’ve just been abducted.

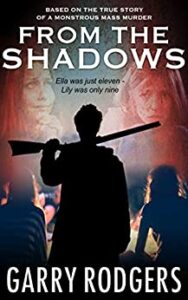

Garry Rodgers has lived the life he writes about. Garry is a retired homicide detective and forensic coroner who also served as a sniper on British SAS-trained Emergency Response Teams. Today, he’s an investigative crime writer and successful author with a popular blog at

Garry Rodgers has lived the life he writes about. Garry is a retired homicide detective and forensic coroner who also served as a sniper on British SAS-trained Emergency Response Teams. Today, he’s an investigative crime writer and successful author with a popular blog at