Today’s post is an excerpt from my new writing book, “Story Fix: Transform Your Novel From Broken to Brilliant.”

This is the eleventh chapter, out of 15 plus an Introduction, and thus it is written in context to what I believe to be the highest ambition of the book: to show you two things… the scary roster of stuff that can conspire to contribute to your novel being rejected (and how to reduce that risk)… and the inherent opportunity that awaits those who seek to understand the reasons why it was rejected.

Too often, upon hearing the dark news, writers simply find a new target and sent out another submission. As if the rejecting agent or editor has their head up their… sweater.

Maybe.

Just as often, the rejecting party – an agent or a publisher – doesn’t provide any real feedback from which the author might embark upon an upgrade, if not outright repair of the manuscript.

And thus (and herein commences the excerpt)…

Welcome to the Bermuda Triangle of Storytelling.

Your story is a vessel. It must float on a sea of possibility. If the weight of absurdity, familiarity, or underachievement is too heavy, the boat will sink. The relationship between an idea, a concept, and a premise defines the Bermuda Triangle of storytelling, where well-intentioned writers too often set sail without the right navigation, sensibility, or awareness to avoid being swallowed alive.

Surviving these deadly waters requires more than knowing how to swim (i.e., how to write nice sentences), or having an interesting idea alone. It’s knowing how to navigate the waters of a story, with a vessel that is strong and seaworthy.

After reading the chapters thus far, this is, of course, old news. But what remains floating is perhaps our willingness to embrace it all, to allow the principles to flow in as our limited beliefs are dumped overboard. That, like storytelling itself, is sometimes a hard thing to accomplish.

There’s a reason why revision is so freaking hard.

But if you think about it, it shouldn’t be. With all these principles and tools, it should at least be manageable. The damage is sitting in the rejected draft, staring back at you, mocking you, or it’s ringing in your ears from an outside source. The upside should position revision as more of a gift than a burden, but that’s sometimes hard to see, because you are either in denial, or you know it was you who did it that way in the first place, working with the best of intentions and without the slightest clue you were mismanaging the moment. So now, armed only with a new awareness, perhaps a need you don’t even understand, you’re supposed to suddenly bring something different to the process of fixing it?

This is craziness in its purest form.

If you’re a professional writer seeking representation from an agent, or to land a contract from a publisher, or even just to earn a little buzz in the crowded wilderness of self-published fiction, then one thing is beyond argument: Rejection hurts. It sucks on so many levels, even though the public writing conversation has assured you this was coming, because it always does. It still hurts.

And yet, despite the pain, and unlike so many other avocations that we embrace because they are fun and personally (versus professionally) rewarding, rejection matters. Hey, we believe we’re pretty good at the stuff we do personally: dancing, karaoke, golf, painting, poker, knitting, ping pong, bodybuilding, cooking. You can play crappy golf or tennis or bridge every weekend for the rest of your life, and it doesn’t change your experience or alter your future. You’re still having a good time. But this isn’t the case with writing. We thrive on hope, on the belief that our efforts are actually leading us toward something.

Pain exists not because it is an issue of winning or losing but rather because it is a measure of personal identity and ambition. Rejection threatens our dream. But that perception is exactly backwards. Rejection reminds us how hard this is, dashing hope in the process, and yet perhaps fueling us with an ambition that seeks to find an upside.

While you likely wouldn’t think to declare yourself a professional in your weekend recreational pursuits, as a writer, otherwise worldly and wise, you might consider yourself a professional even now. You go to writing conferences, read writing books, seek representation, and suddenly, because you absolutely do intend to sell your work, you bestow upon yourself the mantle of the professional. Which means—and here is a rarely spoken truth—you are competing with everyone else at the writing conference, if for nothing else than mindshare and respect from agents and editors. The respect and props you seek from them are defined by how your story compares to everyone else’s.

But you opted in as a professional, not a weekend warrior. Which means you don’t get to take it personally. For the enlightened professional, the call for revision becomes an opportunity rather than a reminder of your limitations.

And yet, it seems so … daunting.

What you hear at the writing conference, particularly when it comes to the revision process, may not take you where you want to go. Not because the advice you pick up is wrong, per se, but because it can be imprecise. It comes at you in pieces, little chunks of conventional wisdom floating alone and unconnected—as from a workshop on how to write better dialogue, for example—on a sea of assumed yet less-than-clear relevance to a bigger picture.

So you’re saying better dialogue will make my novel better? The answer is: Sure it will. Always. But then there’s this slightly different question: So you’re saying that writing better dialogue will get me published?

This is why many writers drink.

And why writing teachers exist at the very edge of madness.

The bigger picture will save you.

When your story requires revision, chances are something you’ve done doesn’t fully align with the principles that show us how a story works, and it can be found at the story level rather than the craft level.

The sow’s ear, chicken-droppings level.

Listen closely … that sound in your head may be your inner author trying to tell you something. And chances are you really need to hear it.

The more you know about the craft of storytelling, the louder that voice becomes. The more you know about storytelling—both at the story level and the craft level—the clearer the message itself will be. Our profession is full of writers who hear the call. They acknowledge doubt in the form of that inner voice telling them something is off the mark, but they don’t really know how to respond. Usually they respond by submitting it somewhere else to see what happens, hoping to confirm their suspicion that the first agent or editor was having a bad day.

And then it comes back to you with the same outcome. And the voice telling you to revise becomes louder and more impatient.

The enlightened writer listens.

You’ve been introduced to the tools, criteria, and benchmarks of a strong story that can be applied to the revision process, as well as to a first draft. Maybe you haven’t yet internalized them. Maybe you zoned out when they were being presented at the writing conference. Maybe you opted for the session on how to land an agent instead. Maybe you prefer the indulgent musings of keynote speakers who wax eloquent about the mystery of it all, the muse that channels through them, the characters that speak to them, the immersion in their process with the trust that somehow, some way, someday, their story will finally make sense.

Here’s a newsflash for those writers who like to tell their friends that there is something mystical in what we do: There are no actual muses (there are inspirations, which are different animals), and your characters don’t talk to you. When stories are broken—they are very much like friends and relatives and politicians in this regard—they’re not going to confess to their sins and give you a strategy for healing. No, the voices you ascribe to muses and talking characters are you, speaking to yourself from a place of story sensibility, which for better or worse is the sum and nuance of all that you’ve read and studied and learned and concluded on your writing journey.

You’ll finally hear it—it’ll sound a lot like an improved sense of story when you do—because it makes sense to you. Because you’ve had your fill of pain and frustration, and you’re finally opening up to higher thinking.

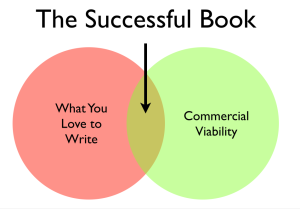

Seeking the Sweet Spot

I offer this next point from my experience presenting writing workshops for the last twenty-five years. Writers arrive in the room with certain belief systems about writing that defines what is and isn’t true in their minds. This causes them to be resistant to anything that challenges those beliefs and leads to a rather strong sense of confidence that what they’ve written, or intend to write, is rock solid and infused with genius. When something challenges that assumption—like someone saying that your characters don’t talk to you, or that there may be a better path for your story—they shut down to some extent. They are processing the contradictions, the perception of falsehood hanging in the air, and thus don’t completely perceive the meaning and inherent opportunity in what’s being presented.

Some readers of this book will, at this point, not clearly comprehend a critical nuance: that the process of story fixing isn’t just for rejected books, it’s for any story that seeks to become a better story. And complicating this is the cold, hard truth that some rejected books aren’t necessarily broken at all; they simply may not have landed in the sweet spot, at the right time, of their publishing journey. In this sense, revision is merely a form of starting over, building your best story from the inside out, from the ground up, from the truth of the principles that will never steer you wrong.

To Revise Or Not To Revise

Then again, every rejection slip does not necessarily signal the need for a major revision. Your story may be perfectly fine as is. The rejection may come from a source you do not understand, and therefore do not value. More often, though, harsh criticism and rejection may actually be the wake-up call the writer needs. And thus, it’s on the shoulders of the writer to know the difference—timing rather than a lack of sufficient craft—and to use feedback in all its forms to accurately assess the story’s strengths and weaknesses and apply that feedback to move forward accordingly. The tools and processes apply to any origin of the need for story repair, however it is conveyed—be it a rejection or simply a depressing hunch that won’t leave you alone.

Worthy stories, some of which go on to success, certainly do get rejected all the time, both by agents and publishers. These are the stuff of urban legend. Do a quick Google search and you’ll find them everywhere. I’ll mention again the quote from esteemed author William Goldman: “Nobody knows anything.”

It’s too true. But it’s also a risky way to place your bet. Because you could rationalize the rejection of your story as simply a case of timing or another agent who doesn’t get it rather than a legitimate red flag that should get your attention. We can be sure that Kathryn Stockett didn’t revise her manuscript forty-six times, one for each instance of rejection. But because she hasn’t talked about it, we can’t say for sure how those rejections colored her subsequent sequence of drafts, if at all.

Right here is where a paradox kicks in: If you don’t possess the knowledge to nail it the first time out, and are now stuck with the need to revise, how can you leverage feedback and rejection in the writing of a subsequent draft to solve those problems? You’re the same writer who wrote that flawed story. How can you suddenly, without elevating your skill set, attempt to hoist good toward greatness? That’s like asking a toddler who has just fallen off his bicycle to simply get back up and try it again, without showing him what went wrong. A lot of fathers have tried just that method over the years—“It builds character,” they say—and it’s always a recipe for further frustration and tears, as well as a few Band-Aids.

You can’t expect to take your story higher with the same skill set as before, at least to the extent that you don’t understand the feedback itself. But you’re here, you’re learning the unique tools and principles that drive successful revision, and that just might change everything about your next swing at the story.

As professional writers we are beyond the need to use our work as a means of personal character building. We require knowledge applied toward the growth of something much more amorphous and elusive: a heightened storytelling sense.

“Writing the novel is half the battle. The other half is fixing it. In this book, master craftsman Larry Brooks gives you his set of tools for the fix-it stage. So strap on your belt, and get to work!” — James Scott Bell, author of Write Great Fiction: Plot & Structure