by Robert Dugoni, bestselling thriller writer and writing coach

by Robert Dugoni, bestselling thriller writer and writing coach

[Note from Jodie: I’m going crazy with last-minute preparations for my big move across the country

in a few days, so bestselling thriller author and writing instructor Robert Dugoni is filling in for me today. Take it away, Bob!]

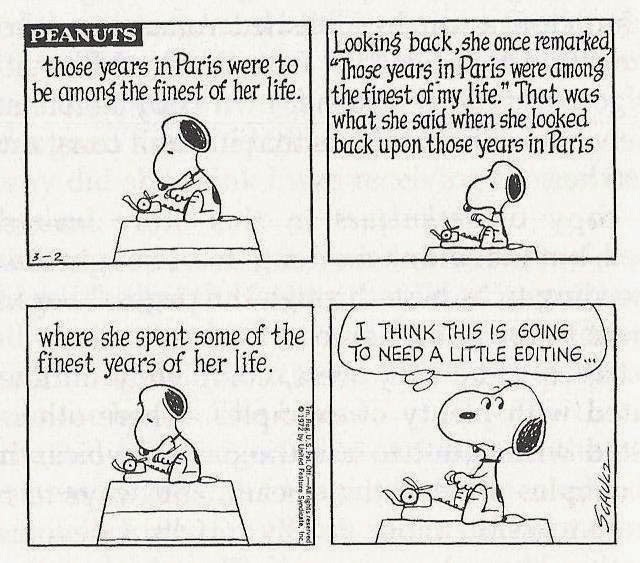

I raise more than a few eyebrows when I teach, and that’s usually a good sign. I know I’ve got my students thinking. The first collective class-eyebrow-arch comes when I stand up and say, “No one can teach you how to write.” Students who’ve paid good money to be in one of my seminars or workshops begin to have immediate heart palpitations until I add, “But I can teach you how to teach yourselves how to write.”

So what do I mean by this?

How can I teach any student I don’t know intimately what to write or how to write it? I can’t even teach my two children how to write. Writing is an extraordinarily personal endeavor and each of us brings our own nuances, quirks, insights and experiences to not only what we write but how we write it. All of these things form what we frequently refer to as the writer’s “voice” – how the writer (and really her characters) views the world and others in it and how the character expresses that view. We hope that it is a unique and exciting and interesting. When it is, those are usually the novels publishers clamor to buy.

But the fact is the to-be-published novel will never make it that far if the author forsakes the craft of writing and makes one of those silly mistakes that cry out “amateur” to that would-be editor.

So rather than telling students “I can teach you how to write,” I tell them my job is “to remove as many obstacles in the path to publication as possible.”

One of those big obstacles is when the author intrudes into the story.

Author intrusions into the reader’s experience reading a novel can be deadly. Not only do they raise the “amateur” flag and slow the story pace, they also tend to annoy. It’s like being in a deep and meaningful conversation with one person and having another person continually interrupt that conversation to tell you things you really don’t need to know at that moment or, frankly, you don’t care about!

When a story unfolds, the opening chapters should develop like a play on a stage. The reader wants to see what the character sees, hear what she hears, smell what she smells, taste what she tastes, and touch what she touches. It is not the author experiencing the story. It is the reader experiencing the story through the character. So how does the author intrude?

Let us count just some of the ways.

~ Omniscient narrative

This occurs when you’re reading a scene from a particular character’s point of view and suddenly the author barges in to provide a bit of information that the character doesn’t yet know, couldn’t yet know and may never know. Sometimes this is called bad foreshadowing. Here’s an example:

You’ve just written a killer scene in which your protagonist has arrived at a mountain getaway for three days of R&R and the author ends the scene with something like, “Little did she know that three miles away, Luke Reddinger, a serial killer, had just escaped from the state penitentiary.” Okay, so if the character didn’t know, who’s throwing in this tidbit? Does the reader need it at that moment? Would it be more powerful to see Luke Reddinger escaping, or running through the woods, maybe seeing the cabin she has arrived at? Wouldn’t that raise a story question that would keep the reader reading to find out what happens? Isn’t that what every writer wants?

~ Unnecessary biographical information

Ever read a scene in a book that is going swimmingly when suddenly the author stops the flow of the dialogue and action to tell you where the main character went to high school, their major in college or that their great grandmother was an alcoholic? Unless that high school is going to play a part in the story, the major is important to illustrate the character’s skill, or grandma is a serial killer when she gets drunk, what was the point of interrupting the story? Biographical sketches, if you’re so inclined to do them, are for the author to get to know her characters so the author better understands how the character will act and what she might say in a particular situation or moment. They are not for the reader.

~ Author Opinions

Nothing is more transparent than when an author tries to ram her opinion on a topic down your throat. Even when the author tries to disguise the opinion as a “character’s opinion” it is usually easy to spot. “Mary asked John what he thought about President Obama’s health care reform.” And then John starts spouting off. This is one of those instances where the author would be better off showing rather than telling. If you want to make a statement about the death penalty, write The Green Mile and let us see one of the pitfalls of the ultimate punishment. You want to write about abortion, write The Cider House Rules. You want to write on the evils of slavery, write Twelve Years a Slave. Racism in the south – Mississippi Burning. Greed in the roaring twenties – The Great Gatsby. There’s no place like home – The Wizard of Oz. And so on…

~ Flashbacks

This is usually the cause of the third collective class-eyebrow-arch. Some even snap at this point. Why? Because so many of us use flashbacks in our novels. So before anyone snaps an eyebrow, let me clarify – flashbacks can be used. The author just needs to know how to use them so they are not an intrusion. First, a flashback, despite its name, must still move the story forward. That is, the flashback should impart some information that is relevant to the plot at that moment, drives the plot forward, and/or reveals some important character trait or relationship that will come into play.

Second, a flashback is a scene. Therefore, all of the things discussed above that go into making a great scene still apply. A flashback should not be some character sitting alone at a table reminiscing about something that happened in the past. Put the reader in the scene with the characters and allow the reader to hear and see and smell and taste and touch the scene as it unfolds.

Think about the movie Titanic. Regardless of your opinion on the movie itself, note that it was actually Rose reminiscing about her voyage on that ship. How boring would it have been if the entire three-hour movie was Rose sitting at a table telling the movie audience what happened, rather than the movie audience flashing back to that time and getting the chance to experience it?

~ Information Dumps

This is usually where the writer has done a lot of research on a particular subject and darn it, everyone is going to know it! An information dump is an excessive amount of unnecessary information or details dumped into the story when the character does not need it and might never need it. Like biographies, research is for the author, not the reader. I’d say less than 10% of the information I research and learn about goes into my novels.

Information dumps can take many forms.

Research details. The research dump is when the author has learned a lot of information on a particular subject and dumps it into the story either in omniscient narrative or thinly disguised by creating a “character” to tell the reader everything they needed to know about such things as growing vegetables on rooftop gardens in New York City during the depression.

Character descriptions. Other information dumps are excessive details about what every character who comes on stage is wearing, or looks like. What the character is wearing is only important if the author has set the scene up so that another character has a particular interest in what a particular character is wearing, or the character’s own choice of clothes is important. When your character walks into a high school prom we can assume the girls are wearing prom dresses and the guys are in tuxedos. But if you’ve set the story up so that Billy is determined to make a splash and wears a tear-away tuxedo intending to leave high school by doing the Full Monty, then we want to know the details of that tear-away tuxedo.

Setting. The same is true with excessive details to describe a setting. Authors are not weather men or travel guides so your scenes shouldn’t read like a weather report or travel book. And if your protagonist is running for her life through a forest while being chased by werewolves, please don’t have her take the time to tell us every species of tree and type of fauna they are running past. Necessary details only. Excessive details need not apply!

So when you have the urge to pontificate, opine, brag, or otherwise bore, think about what my friend and brilliant writer John Hough Jr always says: “Dialogue is action and action is dialogue.” Get your characters on the move and talking. Avoid staying too long in a character’s head. Do your biographies and research for you, not for the reader, and give us only those details that will keep the story moving forward.

And above all, once you’ve hooked us with an incredible opening, lured us in with an amazing character, and mesmerized us with a killer plot, then please, BUTT OUT! I’ll thank you to let me enjoy your beautifully crafted story on my own.

Robert Dugoni is the critically acclaimed New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post and #1 Amazon bestselling author of the Tracy Crosswhite police series set in Seattle, which has sold more than 7 million books worldwide. He is also the author of The Charles Jenkins espionage series, and the David Sloane legal thriller series. He is also the author of several stand-alone novels including The 7th Canon, Damage Control, and the literary novel, The Extraordinary Life of Sam Hell – Suspense Magazine’s 2018 Book of the Year, for which Dugoni’s narration won an AudioFile Earphones Award; as well as the nonfiction exposé The Cyanide Canary, a Washington Post Best Book of the Year. Several of his novels have been optioned for movies and television series. Dugoni is the recipient of the Nancy Pearl Award for Fiction and a three-time winner of the Friends of Mystery Spotted Owl Award for best novel set in the Pacific Northwest. He is also a two-time finalist for the International Thriller Award, the Harper Lee Prize for Legal Fiction, the Silver Falchion Award for mystery, and the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award.

Robert Dugoni’s books are sold in more than twenty-five countries and have been translated into more than thirty languages.

Visit his website at www.robertdugoni.com, and follow him on twitter @robertdugoni and on Facebook at www.facebook.com/AuthorRobertDugoni

Coming soon:THE SHIELD by Sholes & Moore

Coming soon:THE SHIELD by Sholes & Moore