Time Warps and the ING Construction

Terry Odell

UPDATE: My audiobook narrator, Steve “Captain” Marvel was unable to respond to comments on the post where I interviewed him. He has now replied to those who left comments. You can find the post here. He’s graciously left his email address in a reply should anyone need to follow up.

UPDATE: My audiobook narrator, Steve “Captain” Marvel was unable to respond to comments on the post where I interviewed him. He has now replied to those who left comments. You can find the post here. He’s graciously left his email address in a reply should anyone need to follow up.

I’m on my way to Montana to attend the Authors of the Flathead Writing Conference. I did a Zoom presentation for their group at Debbie Burke’s request, and had a good time talking to people who understood the “writer’s mindset.” So much so that I registered for their conference and am looking forward to meeting Debbie in person.

I’m on my way to Montana to attend the Authors of the Flathead Writing Conference. I did a Zoom presentation for their group at Debbie Burke’s request, and had a good time talking to people who understood the “writer’s mindset.” So much so that I registered for their conference and am looking forward to meeting Debbie in person.

I’m revisiting a topic I’ve addressed before, triggered by a recent read of a traditionally published author’s book. (Why do we feel it’s necessary to differentiate between traditionally published and indie publishers?) Anyway my guess is both the author and the editor didn’t grasp the fine points of the “ing” construction, and this book had countless misusages of the ‘simultaneous action’ that goes along with those “ing” clauses, resulting in numerous time warps.

You don’t have to read science fiction to run into a time warp. At the very first writer’s conference I attended, an agent said she would reject a query with more than 1 sentence beginning with the “ing” construction. Her explanation—it’s too easy to make mistakes with that sentence structure.

But is it wrong? No. You have to be careful, and you have to pay attention. There are different reasons to avoid, or minimize use of those pesky “ing” words.

First, the inadvertent time warp.

Unlocking the door, Fred dropped the mail on the table and poured himself a drink. Using that “ing” phrase shows simultaneous action (or it’s supposed to), and Fred couldn’t have done all that while he was unlocking the door. Time warp!

Better to write After unlocking the door, Fred dropped the mail on the table, then went to the liquor cabinet to pour himself a drink. Time moves forward in that one.

What’s wrong with these sentences?

“Running across the clearing, John rushed into the tent.”

“Opening the door, Mary tripped down the stairs.”

John can’t be getting into the tent while he’s running across the clearing. And Mary needs to open the door before she goes downstairs.

Next, the misplaced modifier

In my first critique group, I held the prize for creating an answering machine that gave neck massages. In my draft of Finding Sarah, I’d written, “Rubbing her neck, the blinking red light on the answering machine caught Sarah’s eye.” Ooops. (But I would like a machine with that function!)

Make sure the noun or pronoun comes immediately after the descriptive phrase. Thus, the above example could be “Rubbing her neck, Sarah noticed the blinking red light on the answering machine.”If your “ing” verb follows “was”, take another look. “John was running across the clearing” isn’t a strong as “John ran across the clearing.” Of course, you’ll want to use stronger verbs, such as raced, sped, or barreled, but the idea is the same.

When you’re looking over your manuscript, you might want to flag words ending in “ing” and take another look to be sure you haven’t made any of these basic errors.

Here’s a quick way to spot them in Word. Click the image to enlarge.

In your document, click the drop down arrow by “Find” then select “Advanced Find.”

In your document, click the drop down arrow by “Find” then select “Advanced Find.”

Click “More” and then check the “Use Wildcard” Box. Type ing into the find field, then click the “Special” Option, and “End of Word.” This will add a > character. You can use the Reading Highlight to see all of them, and the “Find Next” to deal with them one at a time. You’ll get more than just verbs ending in ing, but it’s still a quick way to spot them. The hard part is determining whether you’ve got a problem!

What grammar “conventions” do you have trouble with? Which bother you when reading?

Available Now

Available Now

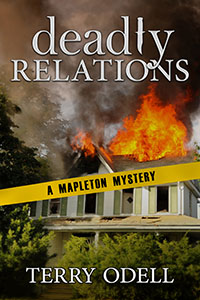

Deadly Relations.

Nothing Ever Happens in Mapleton … Until it Does

Gordon Hepler, Mapleton, Colorado’s Police Chief, is called away from a quiet Sunday with his wife to an emergency situation at the home he’s planning to sell. A man has chained himself to the front porch, threatening to set off an explosive.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Passive voice is something else again. Consider The dog bit the boy versus the boy was bitten by the dog. The former is active voice, the latter is passive voice. (I know someone out there is saying, “But what about The dog was bitten by the boy? That’s passive voice, but unexpected, and therefore more interesting.)

Passive voice is something else again. Consider The dog bit the boy versus the boy was bitten by the dog. The former is active voice, the latter is passive voice. (I know someone out there is saying, “But what about The dog was bitten by the boy? That’s passive voice, but unexpected, and therefore more interesting.)