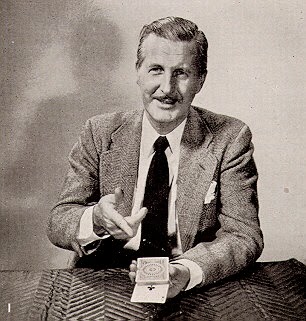

In his introduction to Stephen King’s first collection of short stories, Night Shift, John D. MacDonald explains what it takes to become a successful writer. Diligence, a love of words, and empathy for people are three big factors. But he sums up the primary element this way: “Story. Dammit, story!”

In his introduction to Stephen King’s first collection of short stories, Night Shift, John D. MacDonald explains what it takes to become a successful writer. Diligence, a love of words, and empathy for people are three big factors. But he sums up the primary element this way: “Story. Dammit, story!”

And what is story? It is, says MacDonald, “something happening to somebody you have been led to care about.”

I want to home in on that something happening bit. It is the soil in which plot is planted, watered, and harvested for glorious consumption by the reader. Without it, the reading experience can quickly become a dry biscuit, with no butter or honey in sight.

Mind you, there are readers who like dry biscuits. Just not very many.

MacDonald reminds us that without the “something happening” you do not have story at all. What you have is a collection of words that may at times fly, but end up frustrating more than it entertains.

I thought of MacDonald’s essay when I came across an amusing (at least to me) letter that had been written to James Joyce about his novel Ulysses. Amusing because the letter was penned by no less a luminary than Carl Jung, one of the giants of 20th century psychology.

Here, in part, is what Jung wrote to Joyce (courtesy of Brain Pickings):

I had an uncle whose thinking was always to the point. One day he stopped me on the street and asked, “Do you know how the devil tortures the souls in hell?” When I said no, he declared, “He keeps them waiting.” And with that he walked away. This remark occurred to me when I was ploughing through Ulysses for the first time. Every sentence raises an expectation which is not fulfilled; finally, out of sheer resignation, you come to expect nothing any longer. Then, bit by bit, again to your horror, it dawns upon you that in all truth you have hit the nail on the head. It is actual fact that nothing happens and nothing comes of it, and yet a secret expectation at war with hopeless resignation drags the reader from page to page … You read and read and read and you pretend to understand what you read. Occasionally you drop through an air pocket into another sentence, but when once the proper degree of resignation has been reached you accustom yourself to anything. So I, too, read to page one hundred and thirty-five with despair in my heart, falling asleep twice on the way … Nothing comes to meet the reader, everything turns away from him, leaving him gaping after it. The book is always up and away, dissatisfied with itself, ironic, sardonic, virulent, contemptuous, sad, despairing, and bitter …

Now, I’m no Joyce scholar, and I’m sure there are champions of Ulysses who might want to argue with Jung and maybe kick him in the id, but I think he speaks for the majority of those who made an attempt at reading the novel and felt that “nothing came to meet them.”

I felt a bit of the same about the movie Cake, starring Jennifer Aniston. When the Oscar nominations came out earlier this year it was said that Aniston was “snubbed” by not getting a nod. I entirely agree. Aniston is brilliant in this dramatic turn.

The problem the voters had, I think, is that the film feels more like a series of disconnected scenes than a coherently designed, three-act story. The effect is that after about thirty minutes the film begins to drag, even though Aniston is acting up a storm. Good acting is not enough to make a story.

Just as beautiful prose is not enough to make a novel. Years ago a certain writing instructor taught popular workshops on freeing up the mind and letting the words flow. The workshops were good as far as they went, but this instructor taught nothing about plot or structure. Finally the day came when the instructor wrote a novel. It was highly anticipated, but ultimately tanked with critics and buyers. And me. As I suspected, there were passages of great beauty and lyricism, but there was no compelling plot. No “something happening to someone we have been led to care about.”

Of course, when beautiful prose meets a compelling character, and things do happen in a structured flow, you’ve got everything going for you. But prose should be the servant, not the master, of your tale.

Let me suggest an exercise. Watch Casablanca again. Pause the film every ten minutes or so, and ask:

1. What is happening?

2. Why do I care about Rick? (i.e., what does he do that makes him a character worth watching?)

3. Why do I want to keep watching?

You can analyze any book or film in this way and it will be highly instructive. You’ll develop a sense of when your own novel is bogging down. You can then give yourself a little Story. Dammit, story! kick in the rear.