Reader Friday – Good and Bad Investments

Image by congerdesign from Pixabay

What is the best investment you ever made to grow your writing career? (Doesn’t have to be monetary.)

For me: Going indie.

What about the worst?

Not firing my agent.

Reader Friday – Good and Bad Investments

Image by congerdesign from Pixabay

What is the best investment you ever made to grow your writing career? (Doesn’t have to be monetary.)

For me: Going indie.

What about the worst?

Not firing my agent.

Reader Friday – Traditions.

Sundown today marks the start of the year 5781 on the Jewish calendar. Our family tradition revolves around the meal (which is true for virtually all Jewish holidays–they tried to kill us, we prevailed, let’s eat). Sweet dishes are the norm on Rosh Hashanah, to kick the new year off to a sweet start. At our table, dessert is always Pflaumkuchen (plum cake). The recipe varied, depending on which relative was in charge of dessert, and living where we do now, prune plums are almost impossible to get, but regardless of the details, it’s always going to be plum cake for dessert.

Sundown today marks the start of the year 5781 on the Jewish calendar. Our family tradition revolves around the meal (which is true for virtually all Jewish holidays–they tried to kill us, we prevailed, let’s eat). Sweet dishes are the norm on Rosh Hashanah, to kick the new year off to a sweet start. At our table, dessert is always Pflaumkuchen (plum cake). The recipe varied, depending on which relative was in charge of dessert, and living where we do now, prune plums are almost impossible to get, but regardless of the details, it’s always going to be plum cake for dessert.

Any holiday traditions you’d like to share, food or otherwise? Have you ever included them in your writing?

Going Wide–or Don’t Put All Your Eggs In One Basket.

Terry Odell

Image by Varintorn Kantawong from Pixabay

Garry had an excellent post going into great depth for using Amazon to self publish, tips that are useful for anyone putting their own books out there. I use Amazon, and it makes up a strong percentage of my writing income, but I’m a strong proponent of going wide. For me, it’s about people, and not everyone shops Amazon, especially internationally. I’ve reached readers in countries I’ve never heard of via Kobo’s platform. (Not that geography was ever my strong suit.)

Another perk of going wide is being able to set your book’s price to free at any time. I’ve found offering first in series free for several of my series is an excellent way to attract readers and drive them to the rest of the books. Amazon will price match–maybe, but it often takes some effort. Plus, as I understand it, the KDP Select TOS say you can’t distribute enrolled ebooks for free, so giving them away via services like BookFunnel, etc., as reader magnets or rewards is off the table. Many readers who subscribe to Kindle Unlimited are the sort who want lots of books at little or no cost, and I prefer to attract readers who are willing to pay for books, not wait for free days. However, going wide opens the door for other subscription services such as Scribd or Kobo Plus.

First, my personal history. When I started writing, which wasn’t all that long ago, I was with digital publishers. There was no Amazon, so each publisher had its own website with its own store. Digital publishing got its push with Ellora’s Cave, because they published erotica (which they called “romantica”). Privacy was a huge selling point. Readers could buy books on line and read them on their PDAs. (Yes, it was that long ago.)

Then, Amazon came into the mix, and digital publishing took off. For all practical purposes, they were now the “only” game in town, and when my traditional publisher remaindered my first book, it seemed reasonable to give Amazon a try. I wasn’t a huge name, so sales weren’t great, but it was a new way to reach readers with ebooks, since the publisher printed only in hard cover and targeted libraries, not bookstores. There was no monetary investment, so I had nothing to lose.

As I recall, Smashwords appeared shortly thereafter, and Barnes & Noble was next on the digital scene. I added them to my distribution channels. Amazon had just started its “Select” program requiring 90-day exclusivity, and I didn’t want to play that game. (Note: I still don’t.) When Nook came out with its now defunct “Nook First” program, I was in the right place with a new release, and gave them 30-day exclusivity. In return, my book appeared on their home page for a week, and emails promoting my book were sent to anyone who owned a Nook or had bought any of my books. I recall the Hubster saying, “Hey, Barnes & Noble just told me to buy your book,” and my daughter-in-law saying someone at work came up to her and asked if she was related to the author. I made $20,000 that month from Nook sales (and had to give back most of my Social Security and hire a tax guy).

As more channels opened, I added all my titles to each. So, that’s my publishing history. Back then, the technical aspects of getting books formatted was more challenging, but I figured it out, and if I can do it, anyone should be able to, especially now. Some basics are formatting in TNR, 12 point font, 1 inch margins all around and use a paragraph style for indenting, NOT TABS. EVER.

(Note: as more and more e-readers have come out, the end-user has control over things like fonts, etc., so there’s no need to get fancy with formatting. Stick to the recommendations.)

Now, it’s SO much easier. If you’re not comfortable with formatting, Draft2Digital will take your word doc and format it for you. All you really need to start is the doc file (they take docx, rtf, and epub as well). In their words, “If Word can read it, we can, too.” They also give you a choice of “decorations” for chapter headings and scene breaks, as well as drop caps if you want them, or other ‘start of chapter/scene’ options. (But not if you give them an epub.)

(Another note: I don’t justify my digital files because when you up the font, as many readers do, you get huge ugly gaps of white space. Kindle automatically justifies the file. I do justify my print format.)

(Another note: I don’t justify my digital files because when you up the font, as many readers do, you get huge ugly gaps of white space. Kindle automatically justifies the file. I do justify my print format.)

D2D will also create front and back matter, including an “also by the author” page that sends people to Books2Read, a link to a choice of bookstores for the reader. I first used D2D when they were new and the only way to get to Apple without a Mac, but they also distribute to places like Hoopla, Scribd, Tolino, 24 Symbols, and Bibliotheca and OverDrive for libraries.

As digital has grown, so has conversion software, because the better the book looks, and the easier it is to use the channel’s site, the more money you both will make. However, the former author relations guy at Kobo said D2D had the best conversion software out there, and he used them to make his epubs to put up at Kobo.

I go direct to Nook, Kobo, and Kindle and Smashwords because there are some perks available, such as promotion opportunities, discount coupon offers to readers, but D2D will distribute to those channels if you want. I use the epub file that D2D provides (no charge—you can download their epub and mobi formats and don’t even have to publish your book with them.) I’ve used them to create reader magnets for giveaways. I can use that file at Kobo, Nook, Kindle, and Smashwords. Again, the easier the interface is to use, the more likely authors will publish, so following directions at each of the channels is all you need to do. They’re all (of course) slightly different, but if I can figure out where to put the information, anyone should be able to.

Image by Terri Cnudde from Pixabay

It took me longer to establish a readership at the other channels, but now that I have it, I don’t want to lose them. They’re the frosting on my royalty cake. Plus, if Amazon sales sag, the other channels help make up for it.

For the record, I’m a Nook book-buyer, so if a book is exclusive to Amazon, it’s not likely I’ll buy it. Yes, I have the Kindle app, but I prefer the user interface on my Nook. About the only Kindle books I “buy” are the Prime freebies each month, and many months, not even those. Yes, as an author, I make more money selling at Amazon, but exclusivity rubs me the wrong way. My take: The more power we give Amazon, the more they can change the rules to suit their game. This means that if they decide to end Kindle Unlimited, which they could, you’ll have to start from scratch building a wide readership. Putting all my eggs in one basket doesn’t work for me.

You do what works for you, and since I’m retired and don’t need to put food on the table with my book earnings, I prefer to reach more people who will buy my books, not make the most money possible. I write because I can’t imagine not writing.

Questions? Experiences to share? The floor is open.

My new Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is now available at most e-book channels. and in print from Amazon.

My new Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is now available at most e-book channels. and in print from Amazon.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Reader Friday – Remembering 9/11

Image by David Mark from Pixabay

Today is the anniversary of the destruction of the Twin Towers. I know you remember when you heard, and what you were doing. Did this tragedy impact your writing in any way?

Image by Виктория Бородинова from Pixabay

What’s the worst writing/publishing advice anyone ever gave you? Best?

The worst advice I got was from an early critique group leader, when I was writing my first attempt at a novel, who said, “Don’t let anything bad happen to Sarah.” Happy people in happy land, anyone?

Best advice? “Do what you’re good at. Do what you love. Hire out the rest.”

Men Are Not Women With Chest Hair, Part 2

In Part 1, I talked about physiological differences in the way males and females are hard wired.

In Part 1, I talked about physiological differences in the way males and females are hard wired.

Note: Much of the information in these posts comes from workshops by Eileen Dreyer from a RWA conference, and Tracy Montoya’s presentation at a Southern Lights Conference.

This time, I’ll discuss some of the social differences between men and women. Again, these differences are based on physiological differences in the brain, but there are always going to be individual differences. There’s a basic framework, but there are also individual modifications to the finished product. Think of all those apartment complexes, or housing developments with virtually identical houses. Eventually, the owners put their own touches into their homes giving them some individuality. However, some of the broad, sweeping generalizations we make about men and women does have a basis in the differences in the way their brains work.

In Social Situations:

Men are goal oriented.

Women are community builders.

Men are the lone hunters.

Women are communal.

Men are problem solvers.

Women are problem sharers.

A woman will come home from a day at work and complain about something that happened. To a women, sharing troubles is a friendship ritual. To a man, talking about a problem is asking for advice. Thus, the man will offer suggestions as to how to fix it. The woman really doesn’t want his help, she just wants to vent. Men consider talking about a problem a step down in the hierarchy.

Men are likely to explore an idea through argument. Women will shut down, because they want to keep connections open.

Montoya mentioned a study where two men were brought into a room with two chairs facing the front, and told to wait until they were called for an interview. The men sat and talked. When the subjects were two women, the first thing they did was move the chairs so they faced each other.

This ingrained wiring leads to frequent “discussions” where the woman accuses the man of not listening to her when she’s talking to him because he’s not looking at her.

Men define themselves by achievements.

Woman define themselves by relationships.

In the workplace, our hard-wired brains still see the differences between male and female behaviors. Perhaps the reason men don’t see women as “equals” in the workplace is because they simply can’t. They’re perceived as too emotional to be authority figures. Their wiring does make them emotional. But that doesn’t mean they can’t make the necessary decisions. But a woman is more likely to say, “We’re going to talk about “the” rules,” which is ingrained in the nurturing wiring, whereas a man would say, “We’re going to talk about “my” rules,” which fits his hierarchical wiring. Women soften statements, men give orders.

Men and women have different approaches to problem solving.

Men are linear thinkers.

Women think in clusters.

Men compartmentalize.

Women churn things over until the problem is solved

Men are emotionally divorced from problem solving.

Women are emotionally involved in the process.

Men are solitary.

Women are communal.

Men give space.

Women wants a hug.

Men want answers.

Women want support.

For men, help means failure.

Women want to help.

I hope these posts have provided a little insight you can apply when writing characters outside the familiarity of your own gender. If they shed a little light on your own personal relationships, consider that a bonus.

All right, TKZers. The floor is open for discussion.

I’m pleased to announce that my Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is now available at most e-book channels. and in print from Amazon. Note: in honor of my daughter, I’m sharing royalties with the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

I’m pleased to announce that my Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is now available at most e-book channels. and in print from Amazon. Note: in honor of my daughter, I’m sharing royalties with the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

(If you’d like to see some of the pictures I took on my trip, many of which appear as settings in the book, click on the book cover and scroll down to “Special Features.”)

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Men Are Not Women With Chest Hair

Terry Odell

Last week’s post by Elaine Viets reminded me that the different ways (clichés or not) we describe men and women might have some basis in how we’re hard wired. The following post is based on workshop presentations by Eileen Dreyer and Tracy Montoya.

Last week’s post by Elaine Viets reminded me that the different ways (clichés or not) we describe men and women might have some basis in how we’re hard wired. The following post is based on workshop presentations by Eileen Dreyer and Tracy Montoya.

As a writer of romantic suspense, one genre expectation is that stories are told from both the hero and heroine’s points of view. Writing characters outside one’s gender—and this isn’t restricted to the romance genre, or to major characters—is a challenge. As the title of this blog points out, men aren’t women with chest hair. There are some hard-wired differences, and understanding them can make characters ring true for readers.

Although we know that someone with the XX chromosome set is female, and the males are XY, it’s not ‘either-or’. During gestation, at about the 6-8 week point, the fetus undergoes a ‘hormone wash’, which may be highly loaded with estrogen or testosterone. This overlays brain development and influences brain function. So, there’s really a continuum of sexuality.

And – all of these points are generalizations. There will always be exceptions. Don’t shoot the messenger. I’m sharing my workshop notes here.

There are definite differences in brain structure in males and females. Differences are noted at 26 weeks of pregnancy. The brain develops differently in males before sex hormones are produced, so part of the sex differences in the brain is genetic.

Now, cutting to the chase: Humans started out a long, long time ago. Changes in the brain are nowhere near catching up. So, we’re basically hard-wired to survive, but not in this century. Traveling back to the days of early man…

Males are hard-wired as hunters. They have better long range directional skills. They’ve got a better spatial sense. They focus on single tasks, on procreation, they focus on things.

Females are hard-wired as protectors of the nest. They’re communal, have more finely tuned sensory skills, are multi-taskers. They’re non-verbal communicators. They can process and integrate input faster.

Some differences (and remember, these are generalizations)

The hard wiring is evidenced at a very early age. Little girls want to fit in. Little boys like to be the boss. As women, we grow up wanting to be part of the group and don’t like to make waves, whereas for men, it’s about the hierarchy. Girls share secrets, like to connect. Boys want to be higher up the ladder and use language to one-up each other. If that doesn’t work, they may resort to physical means.

Which is why men don’t ask for directions — it puts them ‘one step under’ the person they’re asking for help. And it helps explain why men don’t apologize. That also puts them in a subservient role. Or if they do, it’s more like, “I’m sorry if you feel that way…”

These observations are built around our culture and our language, and are broad generalizations. Patterns, not rules. Regional background, age, and birth order also play a part.

Here’s a real life example of how little boys play the game. Three little boys in a car. One says, “We’re going to Disneyland for four days.” Boy #2 says, “We’re going to Disneyland for FIVE days.” Boy #3 says, “We’re MOVING to Disneyland.” The driver was the father of Boy #3. He was about to step in and admonish his son for lying, but his passenger, Deborah Tannen, a professor of linguistics, stopped him. She explained that they’d just established the pecking order, and his son came out on top. The boys all knew it was a verbal battle, and they knew nobody was moving to Disneyland.

And, on a lighter note (with apologies for the poor video quality):

I’m pleased to announce that my upcoming Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is now available for preorder at most e-book channels. Note: in honor of my daughter, I’m sharing royalties with the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

I’m pleased to announce that my upcoming Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is now available for preorder at most e-book channels. Note: in honor of my daughter, I’m sharing royalties with the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

(If you’d like to see some of the pictures I took on my trip, many of which appear as settings in the book, click on the book title above and scroll down to “Special Features.”)

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Let There Be Light

Terry Odell

Light is important when we’re writing—and I’m not talking about having enough light to work by. I’m talking about how much we can describe in our scenes. One of my critique partners questioned a bit I’d written (yes, it’s from one of my romantic suspense books).

She stepped inside and closed the door behind them. Placing her forefinger over her lips, she shook her head before he could speak. She unbuttoned the top button of his shirt. Then walked her fingers to the second, sliding the disc through the slit in the fabric. Then to the third, then the next, until she’d laid the plaid flannel open, revealing the tight-fitting black tee she’d seen at the pond this morning when he’d given her the shirt off his back.

His comment: “It’s night. Do you need to show one of them turning on a light?” Maybe. More on that in a minute.

In a book I read some years back, the author had made a point of a total power failure on a moonless night. There was no source of light, and the pitch-blackness of the scene was a way for the hero and heroine to have to get “closer” since they couldn’t see.

It didn’t take long for them to end up in bed, but somehow, he was able to see the color of her eyes as they made love. I don’t know whether the author had forgotten she’d set up the scene to have no light, or if she didn’t do her own verifying of what you can and can’t see in total darkness. Yes, our eyes will adapt to dim light, but there has to be some source of light for them to send images to the brain. If you’ve ever taken a cave tour, you’ll know there’s no adapting to total darkness.

In the case of the paragraph I’d written, the character had seen the man’s clothes earlier that day, so she’d probably remember the colors, especially since the tee was black. And you’ll note, I didn’t say “red and green plaid shirt.”

I won’t delve too deeply into biology, but our retinas are lined with rods and cones. Rods function in dim light, but can’t detect color; cones need more light, but they can “see” color. (All the “seeing” is done in the brain, not the eyes.)

We want to describe our scenes, we want our readers to ‘see’ everything, but we have to remember to keep it real. This might mean doing some personal testing—when you wake up before it’s fully light, check to see how much you can actually ‘see’. The ability to see color drops off quickly. So even if you see your hands, or the chair across the room, or the picture on the wall, how much light do you need before you can leave the realm of black and white? What colors do you see first? When it gets dark, what colors drop off first. Divers are probably aware of the way certain colors are no longer detectable as they descend.

Here’s a video showing what happens.

And another quick aside about seeing color. Blue is focused on the front of the retina, red farther back. This makes it very hard for the brain to create an image where both colors are in focus. It’s hard on the eyes. For that reason, it’s probably not wise to have a book cover with red text on a blue background, or vice-versa. You can look up chromostereopsis if you like scientific explanations. For me, I’m fine with “don’t do that because it’s hard to read.”

How do you deal with light and color in your books? Any examples of when it’s done well? How about not well?

I’m pleased to announce that my upcoming Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is now available for preorder at most e-book channels.

I’m pleased to announce that my upcoming Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is now available for preorder at most e-book channels.

(If you’d like to see some of the pictures I took on my trip, many of which appear in the book, click on the book title above and scroll down to “Special Features.”)

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

If They Buy the Premise …

Terry Odell

A comment from my editor on my current manuscript, saying “This should have come up 200 pages ago” was a good reminder about using foreshadowing.

In talking about comedy, Johnny Carson said, “If they buy the premise, they’ll buy the bit.”

In talking about comedy, Johnny Carson said, “If they buy the premise, they’ll buy the bit.”

The same goes for fiction. You have to sell the premise early on. You can’t stop to explain a character’s skill set, motivation, or fear at the height of the action. Nor can you bring in great-uncle Phineas in the last chapter of your mystery and reveal him as the killer. No fair using the deus ex machina method of resolving your story.

Consider Raiders of the Lost Ark. If the movie had opened with Indy in the classroom, would viewers have “bought” that he was really capable of everything he’d have to do in the movie? No, but by showing him in the field in a life-and-death situation first, we’ll accept that he’s a lot more than a mild mannered college professor.

Before James Bond pulls off his miracles, we’ve seen Q show him the gadgets that will save his life. We know MacGyver has a strong background in science, so he’s got the theory and knowledge to pull off his escapes using duct tape and a Swiss Army knife.

Foreshadowing isn’t only for the “Big Stuff,” though. You should consider making sure you’ve set things up for the “Little Stuff” as well. Think of setups as breadcrumbs you scatter for readers to follow.

You should set things up early on, and in a different context. Setup Scenes should occur throughout the book, and should set up minor plot points as well as major ones.

Example. In a scene from my When Danger Calls, my stalwart hero has been tasked with supervising two little girls who are playing with dolls. They come downstairs and show their mom the fancy braids he’s created.

Would my macho covert ops guy really know how to braid a doll’s hair, or did I stick it in because I thought it would be a cool way to move his relationship with the mom along? Would I have to stop the story to explain where he acquired the skill? Not if I’ve shown it, and better to do it in an entirely different context. Earlier in the book, readers see this:

Ryan leafed through the snapshots while he waited for the earth to start revolving again. He knew which one he wanted as soon as he saw it. He remembered the day it had been taken, right after he’d won third prize at the fair with Dynamite, his pony. He’d been so sure he’d get the blue ribbon and hadn’t wanted to pose for the family picture his grandfather insisted on taking. He saw the look in his mother’s eyes. So proud, she’d made him feel like he’d won first prize after all.

There’s no mention of him actually braiding the horse’s mane or tail, but it shows that he’s had experience with horses, all couched in a scene that’s about something entirely different—his emotional reaction to seeing old family photos.

Then, later in the book, when the girls display their dolls’ hairdos, Mom asks where Ryan learned to braid. One of the girls responds, “On real horses. He used to braid their hair. For shows.”

You’ve set the premise, so reader should buy the bit.

We know Indiana Jones is afraid of snakes at the very beginning of the movie. Because of that opening scene, we know to expect something with snakes, which adds to the tension.

Lee Child foreshadows almost everything he shows in his books. In Gone Tomorrow a fellow passenger rambles on about the different kinds of subway cars in New York. That tidbit shows up front and center later on in a high-action climactic scene. And even the little things, that might not be significant plot points, such as the origin of the use of “Hello” to answer the phone will appear, letting the reader know that the character was paying attention, too.

What will lead to book-throwing by readers? How about this?

Hero and heroine are hiding and the villains are closing in. (Since I write romantic suspense as well as mystery, the genre requires both as protagonists, but it could be your hero and partner, or someone he’s been charged to protect.)

The hero is injured. He hands the heroine his gun and asks her if she can shoot. She says, “Of course. I’m a crack shot,” and proceeds to blow the villains away (or worse, has never handled a gun before, but still takes out the bad guys, never missing a shot). Not only that, but she is an expert in first aid and manages to do what’s necessary to save the hero’s life. Plus, she’s an expert trapper and can snare whatever creatures are out there. Or, maybe she has no trouble catching fish. And she can create a gourmet meal out of what she catches. All without disturbing her manicure or coiffure.

Believable? Not if this is the first time you’ve seen these traits. But what if, earlier in the book, the heroine is dusting off her shooting trophies, thinking about how she misses those days. Or she’s cleaning up after a fishing trip. Maybe she has to move her rock climbing gear out of her closet to make room for her cookbooks. You don’t want to dump an entire scene whose only purpose is to show a skill she’ll need later. Keep it subtle, but get it in there.

When you’re writing, it’s important to know what skills your characters need to possess. You might not know when you start the book, but if you’re writing a scene where one of these skills will move the story forward, and there’s no other logical way to deal with the plot, then you owe it to your readers to back up and scatter those breadcrumbs.

What about you? How do you make sure you’re not entering into deus ex machina territory? What kind of breadcrumbs do you scatter? How do you hide the clues?

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

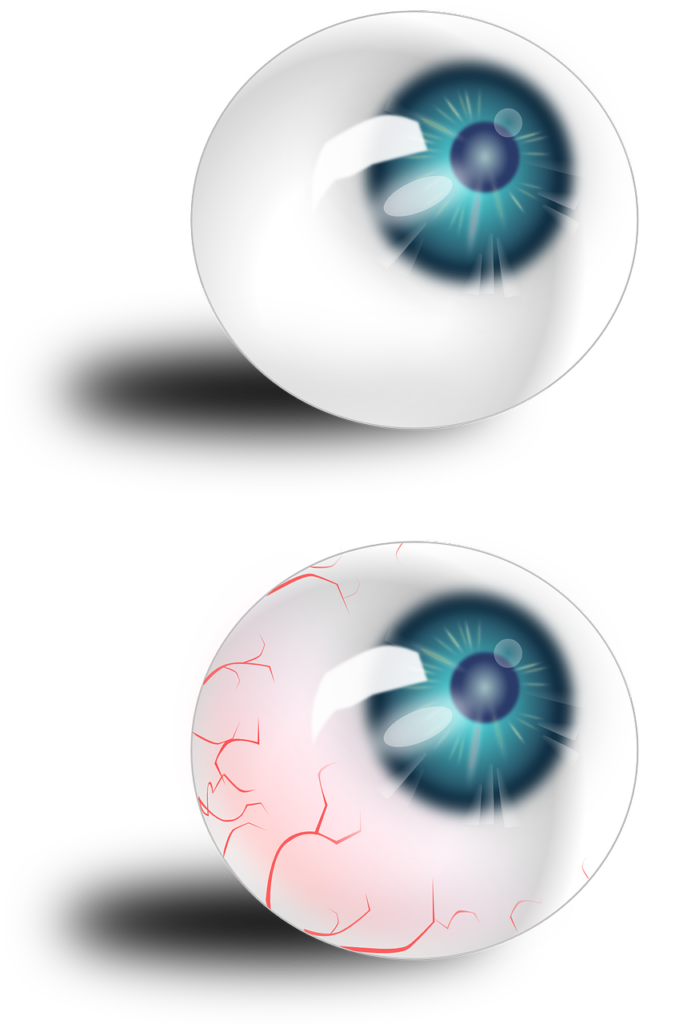

Roaming Body Parts

Image by OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay

I recently read a blog with a firm stance on how to deal with body parts. I don’t entirely agree. I don’t have trouble with figures of speech, and if I’m reading that a character ‘flew down the block to John’s house’ I don’t see her mid-air. If someone writes “a lump of ice settled in her belly” I’m not seeing actual ice.

How do you react when you read things like this?

Their eyes met from across the room.

His eyes raked her body from head to toe.

There seem to be two schools of thought on this one. I’m on the side that doesn’t mind. I understand that ‘eye’ can be used as a noun or a verb. “He eyed her” is acceptable. “He gave her the eye” is an idiom I have no trouble with. I don’t see him extracting an eyeball and handing it to her. So if a characters eyes move, I don’t get visions of eyeballs floating free. Others would substitute the word “gaze.” I’ll use either.

Which side are you on? Would the following pull you out of the story?

Her blue eyes, enlarged by her wire-rimmed glasses, rambled from Colleen’s head to her toes.

“What’s wrong with my face?” Her fingers flew to her cheeks.

Yet there are those for whom those would be book-tossing offenses. Me, I see the eye movement in the first example, but the eyes remain firmly set in their sockets. In the second, my brain assumes the fingers are still attached to the hand, and I don’t think about body parts floating in space.

If you give someone the eye, are you handing them an eyeball? Or if a character eyes the room as he enters, what’s he doing? Eye is a verb as well as a noun, after all. And as a verb, my Synonym Finder (great reference book, by the way) lists view, see, behold, catch sight of, look at. And what about all those expressions using ‘eye’? In a pig’s eye. Do we put things into the eye of that pig? Or, keep an eye out for. Do we take an eyeball out and hold it until someone comes for it?

If we took everything we read literally, a lot of the richness of the language would be lost. If his eyes are pools of molten chocolate, do we really think that he’s got Godiva eyeballs? Or just deep brown eyes?

(That’s a metaphor, I think – if his eyes look like pools of molten chocolate, that would be a simile, right?) I’ve never been good at remembering terminology. Metaphors, similes, idioms, hyperbole—they’re things I use, but I don’t worry about what they’re called when I’m writing them.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.