What was your hardest scene to write? (This could mean “hardest” as in technically or “hardest” as in emotionally.)

Monthly Archives: March 2017

The Great Culling of 2017

I came to an interesting realization this week: I’m afraid of my own Facebook Timeline.

Over the years, I’ve accepted friend requests pretty much as a matter of course, and now the majority of my “friends” are in fact strangers, among whom most are fans, or aspiring writers or friends of others who are. It’s a little like walking out of your bedroom and finding the hallway populated by people you don’t recognize.

I’ve inadvertently allowed my Facebook Timeline to become a marketing platform for my books. Consequently, I need to be circumspect about everything I post there, for fear of affecting my brand. I don’t post adorable pictures of grand-nieces and nephews because it’s wrong to invite strangers into the lives of other family members. It’s crazy.

I have an Author Page on Facebook for fans and potential fans, and it is designed to be a marketing and writer-education platform. That’s where I post relevant items about my books and other projects, and a controlled stream of personal information about myself and my family–just not everything about us. I try to display the me-I-am, but with some of the sharp edges dulled.

So, I have begun the Great Culling of 2017. My plan is to work my way through my Friends List and un-friend anyone whose hand I have not shaken, or with whom I have not had a personal conversation. There will be some exceptions, of course, because I have become quite close with a number of online correspondents whom I’ve never met, and I welcome those people into my life. Before un-friending them, though, I will send a message explaining why, and I’ll provide them a link to my author page. I’ve already heard from a few “friends” who are pissed at being eased out of my house and into the yard, but most seem to understand.

What do you all think? Is this a rude thing to do? Is there a gentle way to tell loyal fans that as much as I love them, I don’t necessarily want them hanging out with the family and me?

A Little “Paws” For PJ

Where History Comes Alive

It’s Spring Break so I will be visiting Teothihuacan outside Mexico City when this blog posts, so my apologies, I probably won’t be able to respond to your comments until later in the day/Monday evening. I’ll be showing my boys these amazing pyramids as they have been studying Mexico’s history in their social studies class. We will also visit the Anthropology museum in Mexico City as well – when traveling with me no one gets to avoid history!

It’s Spring Break so I will be visiting Teothihuacan outside Mexico City when this blog posts, so my apologies, I probably won’t be able to respond to your comments until later in the day/Monday evening. I’ll be showing my boys these amazing pyramids as they have been studying Mexico’s history in their social studies class. We will also visit the Anthropology museum in Mexico City as well – when traveling with me no one gets to avoid history!

One of my favorite parts of research is visiting places and immersing myself in a sense of history. Some places are able to evoke the past easily – as if the past remains stored in the stone walls, cobble stones or timbers of the houses. Other places, however, feel more inaccessible. I find Teothihuacan, with its vast avenue and towering pyramids, is a place that evokes awe but is also so alien in many ways that it is hard to picture what life must have been like way back then. It’s more challenging to imagine the past here but nonetheless the echoes are still there, if you listen hard enough. Likewise, I used to find the Australian landscape much harder to ‘read’ – the aboriginal past seeming to be more elusive and the colonial overtones a little too blunt. By comparison, somewhere like London the past really is omnipresent. For me, the voices of the past are all around and it is easy to imagine the sights, smells and sounds of history.

So TKZers where has history come alive for you? What places have you visited (for research or pleasure) that have evoked the greatest sense of history?

How to Fill the Gaps in Your Plot

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Got the following email the other day:

Dear Mr. Bell,

I recently finished reading your books Super Structure and Write Your Novel From the Middle. They’re awesome, and have taught me a lot about how to better structure a novel. I’ve now sketched out my current novel with the Super Structure beats and feel like I have a solid framework. But the problem I’m running into is filling the spaces between these beats with enough scenes to create a full novel. I’m using Scrivener’s index card feature to write out my scenes, but my poor corkboard looks awfully sparse. 🙂

I recently finished reading your books Super Structure and Write Your Novel From the Middle. They’re awesome, and have taught me a lot about how to better structure a novel. I’ve now sketched out my current novel with the Super Structure beats and feel like I have a solid framework. But the problem I’m running into is filling the spaces between these beats with enough scenes to create a full novel. I’m using Scrivener’s index card feature to write out my scenes, but my poor corkboard looks awfully sparse. 🙂

Do you have any tips or suggestions on how to come up with enough plot to make a whole book? (This is actually a recurring problem for me. I struggle with plotting terribly.)

It’s a great question. Today’s post is my answer.

In Super Structure I describe what I call “signpost scenes.” These are the major structural beats that guarantee a strong foundation for any novel you write.

The idea is that you “drive” from one signpost to another. When you get to a signpost, you can see the next one ahead. How you get to it is up to you. You can plan how, or you can be spontaneous about it.

Or some combination in between!

Now, those who like to map their plots before they begin writing (like my correspondent) can map out all the signposts at the start. But let me give a word to the “pantsers” out there: Don’t be afraid to try some signposting yourself! Because you’ll be doing what pantsers love most–– “spontaneous creativity.” Indeed, signposting before you write will open up even more story fodder for you to play around with. That’s how structure begets story. That’s why story and structure are not at all in conflict. In fact, they are in love.

So let’s discuss those gaps between the signposts. How do you generate material to fill them?

- The “white hot” document

I discussed this recently in my post about chasing down ideas (under the heading “Development.”) This is a focused, free-association document. You start with one hour of fast writing, not thinking about structure at all. Think only about story and characters, and be wild and creative about it. Let the document sit, then come back to it for highlighting, new notes, and more white-hot material.

A few days of this exercise will give you a ton of story material and fresh ideas (hear that, pantsers?). Then you can decide on what’s best and where to fit it.

- The killer scenes exercise

One of my favorite things to do at the beginning of a project is to take a stack of 3 x 5 cards to my local coffee palace and jot down scene ideas as they come to mind. I don’t censor these ideas. I don’t think about where they might go in the overall structure.

When I have 20 or 30 cards, I shuffle them and pull out two at random, and see what this plot development this suggest. Eventually, I take the best scenes and place them between the signposts of Super Structure.

It’s also a breeze to do this in Scrivener, because that program works off an index-card style system. I create a file folder called “Potential Scenes” and put my cards in that file. The added benefit is that I can actually write part of the scene if I want to and it’s all associated with the index card.

- The dictionary game

I have a little pocket dictionary I carry around. When I hit a creative wall, I may open the dictionary at random and pick the first noun I see. I let my mind use that word to create whatever it wants to create, with a little nudging from me toward the actual plot.

- The novel journal

I got this idea from Sue Grafton, who is someday going to break out, I’m sure. She keeps a journal for each novel.

Before she starts writing in the morning, she jots a few personal thoughts in the journal––how she’s feeling that day, what’s going on around her. Then she begins talking to herself about the plot of her book. She works things out on paper (or screen).

This is a great way to talk to your writer’s mind and figure things out. Ask yourself questions about plot gaps that need to be filled or strengthened. Make lists of possibilities.

When I wrote my drafts in Word I used to create a separate document for my novel journal. Now that I draft in Scrivener, I make use of one of its nifty features: project notes.

You can float a notes panel over your Scrivener window that is dedicated to your project. Here is what that looks like (click to enlarge):

Try these techniques (you too, pantser) and you’ll be pleased at how the material piles up. Then it won’t be a matter of wondering what to write, but what to leave out!

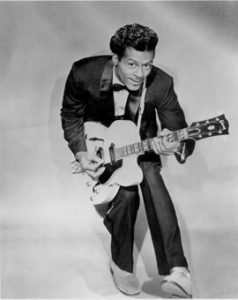

What We Can Learn From Chuck Berry

Chuck Berry left us a week ago at the age of 90. He didn’t begin his music career intending to be a rock ‘n’ roll…star? Icon? Immortal? No. Berry wanted to be a blues singer initially, and that genre would sneak onto his albums here and there (including, I understand, Chuck, an album of new material to be released in June). Rock ‘n’ roll, however, was what paid the bills, and that’s what he did, arguably better than anyone else before or since.

Berry’s lyrics were amazing. He could put years and years of story into a three minute song, with three verses, chorus, and guitar solo. Badda bing bang boom. Go to Spotify (or better yet, your own music collection) and listen to what might be his most widely heard song (if not his most famous one), “You Never Can Tell,” which was prominently featured in the film Pulp Fiction. It’s about a teenage girl and boy who get married — probably too early — but with some hard work acquire an apartment with a “coolerator” full of tv dinners and ginger ale (described in a throwaway line that might be the best single pop song lyric ever written), a stereo with all sorts of 45s, and a flash car. They make a go of it against all odds, and Berry tells you everything you need to know about the whole shootin’ match in two minutes and forty-five seconds through a tune driven by Johnnie Johnson’s piano in the background. A somewhat tragic side note to the song is that Berry wrote the song while in prison. Berry also wrote and recorded his autobiography in three songs that you can listen to in just over seven minutes: “Johnny B. Goode,” the lesser known and bittersweet “Bye Bye Johnny” (which tells the story of his acquired stardom and fledgling motion picture career through the eyes of his mother, who drew out all her money from the bank to buy her son a guitar and put him on that Greyhound bus), and “Promised Land,” the mortar between the bricks of the two other songs. I don’t hang around bus stations (…) but I challenge you to go to one in any city and not hear “Promised Land” playing in your head.

What we can learn from this? Keep in mind that Berry’s art had baked-in limitations. For one, songs had to be relatively short if the artist and record label expected to get them played on the radio. For another, the lyrics had to rhyme. A third was that the clock was ticking. You had to keep putting product out back then to keep your place in radio rotation because some young, hungry upstart was breathing down your neck, hoping to take your place. Berry just painted a picture and kept it simple, particularly in songs like “Carol,” where the singer begs the object of his affection not to go off with someone else, and assures her that he’ll learn to dance if he has to practice all night and day. Berry communicates need and desire in two lines. You and I can do this too. If you have an idea for a story or novel, try to write it from beginning to end in one page (single spaced, 12 font size), from beginning to end. Don’t include every character, car crash, or explosion that you conceptualize. Describe each of your main characters in a medium length sentence, set forth what they are chasing, or after, or trying to achieve — the MacGuffin of the work — and what they are going to do to reach their goal. When you wrap up, provide the ending in terms of emotion or result: happy, sad, death, life, win, lose, or draw. There’s your first step, your blueprint, your demo, what they refer to in Nashville as a “guitar/vocal.” You’re not going to be showing this to anyone so if you feel the need to drift off a bit go ahead and have at it but you’ll at least have something down. Think of Chuck Berry while you do it, and remember that all of those great tunes he recorded were the end result of hours and hours or writing, rehearsal and recording, some of it very frustrating. I’m hoping that at some point a boxed set of alternate takes of Berry’s best known songs is released so that we can get a look at some of the entire process. You’re starting in reverse of what Berry did — you’re going to take something short and make it longer — but the principle of keeping it simple is the same for both.

My questions for you: if you have a favorite Chuck Berry song, what is it? Mine is the live version of “Johnny B. Goode” found on The London Chuck Berry Sessions. Berry starts off playing a ferocious version of “Bye Bye Johnny,” savagely spitting the first verse out, but the crowd, either because of their unfamiliarity with the song or confused by its similarity to “Johnny B. Goode,” starts singing the chorus to “Johnny B. Goode” in unison, startling Berry (“Look at ‘em! Look at ‘em! Sing! Sing, children!”) and causing him to switch to the lyrics of “Johnny B. Goode” for the second verse. Listen all the way to the end, when the M.C. pleads with the crowd to vacate the hall because they’re over time and — Oh, The Humanity! — Pink Floyd fans are waiting outside. Meanwhile, the crowd chants “WE WANT CHUCK! WE WANT CHUCK!”

If you don’t have a favorite Chuck Berry song, what is your favorite song otherwise?

READER FRIDAY: On Writing the Opposite Sex

Monopoly Tokens For Writers?

As you all have probably heard by now, a popular vote has given the world three new tokens for Hasbro’s game of Monopoly: a T-Rex, a Penguin, and a Rubber Ducky are In. The Thimble, Iron, and Wheelbarrow are Out. (Can’t say we’re sorry to see the Thimble go). The closest unsuccessful candidate was a tortoise. Of course, the announcement of the new designs was accompanied by an inevitable bit of controversy about how the new tokens undermined the spirit of the original game. But so far, no dark conspiracy theories have emerged about Rubber Ducky fans rigging the system to give the Boot, the boot, thankfully.

As you all have probably heard by now, a popular vote has given the world three new tokens for Hasbro’s game of Monopoly: a T-Rex, a Penguin, and a Rubber Ducky are In. The Thimble, Iron, and Wheelbarrow are Out. (Can’t say we’re sorry to see the Thimble go). The closest unsuccessful candidate was a tortoise. Of course, the announcement of the new designs was accompanied by an inevitable bit of controversy about how the new tokens undermined the spirit of the original game. But so far, no dark conspiracy theories have emerged about Rubber Ducky fans rigging the system to give the Boot, the boot, thankfully.

It’s too late to vote, but wouldn’t it have been fun to see a writing oriented token in the mix? Perhaps a computer, a paper-filled trash can, or book token?

Are you happy with the winners and losers in the token popular vote? Are you sorry to see any of the old ones go?

Do You Journal?

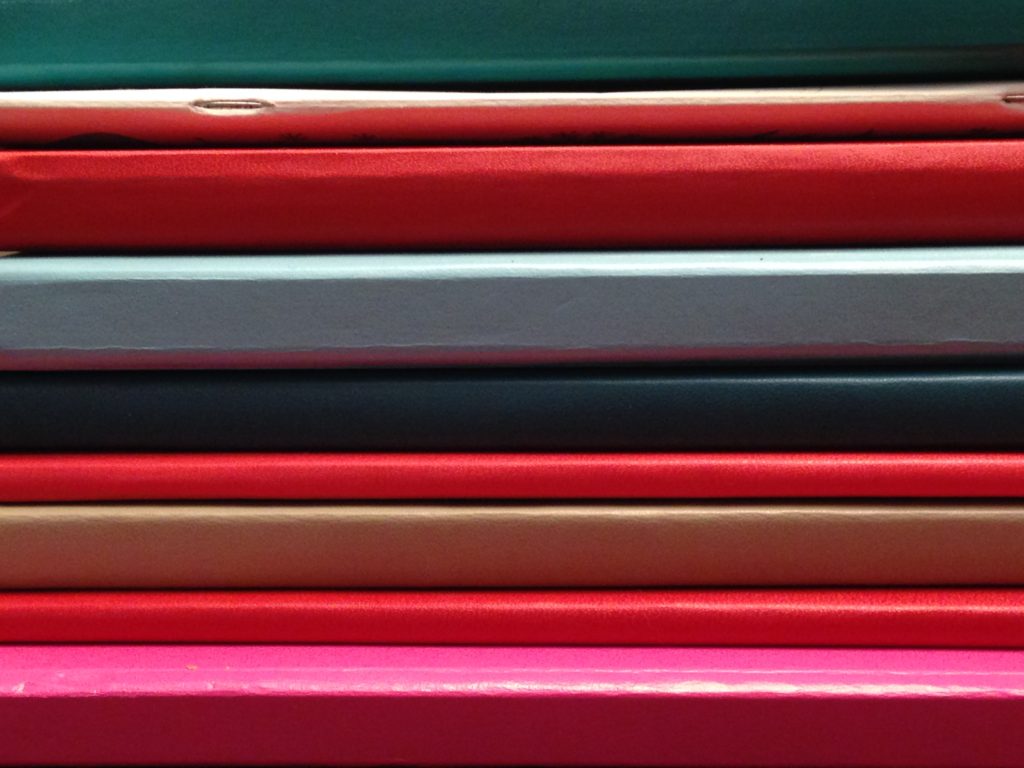

Look at all the lovely notebooks.

From the top:

Emerald Leuchtturm-Current Bullet Journal, containing calendar events, daily schedule, car maintenance, random notes taken when the appropriate journal wasn’t available.

White Paper-Masako Kubo–Stapled, not bound. Last summer’s dream journal, reference.

Red HC Moleskine–Long term ideas for novels and stories since 2011

Light Blue Leuchtturm–Mid-End of 2016 Bullet Journal. I didn’t get into Bullet Journaling until late last year. Now using for blog thoughts and ideas

Teal Flexible Moleskine–Current Morning Pages Journal

Bright Orange Moleskine Notebook–Short story development

Buff Flexible Moleskine--Novel (Formerly The Intruder) WIP notes

Orang/Red Moleskine Notebook–Novel (Untitled cozy–Yeah, gonna give that genre a shot)

Bright Pink Leuchtturm1917 Master Slim–This started out as my 2017 Bullet Journal, but it proved too large for toting around. The 5×8 version (top) fits nicely in any purse or bag. I consider this my Journal of As Yet Unrecognized Possibilities.

For somebody who only owned one non-spiral bound notebook six years ago–the Red HC Moleskine–I’ve certainly made up for lost time. What you don’t see are the notebooks for my last three novels, the Bliss House Trilogy, because I’ve archived them.

As a young writer, I wasn’t much of a journaler. I wanted to write, but I was too embarrassed to write down things that might look silly to other people and carried around my ideas in my head. Of course, journals are meant to be private. I have no idea who I thought would want to even peek at my journals. The words were hardly titillating, the ideas tentative and unpolished. It’s not like I kept money or passwords between the pages.

But now that I’m a woman of a certain age, journals have become critical tools. Not only do I have more pressing/interesting ideas, I also have a memory like a sieve. Journals are my full-body, writerly Spanx. They keep everything tucked in and looking, if not good, at least organized.

I’ve become very attached lately to the notion of ideas floating from writer to writer, looking for the right one to tell the story. It’s an idea I first read of in Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic. She talks about starting to write a novel that had been sort of pestering her–but she struggled, and it just wasn’t happening. So she temporarily shelved it. But then she talked to novelist Ann Pachett, who described her own work-in-progress. And the ideas were nearly identical. But Pachett’s book was going very well, and she later finished it and sold it.

By writing ideas down, I hope to tether them at least for a while. Collect them, live with them, let them nurture themselves with the attention I can give them. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve gone back to the pages of that Red HC Moleskin when I needed a quick idea fix.

Still, it’s a rather intimidating pile of notebooks. They don’t travel easily, and I’ve only recently gotten used to having the Bullet Journal always with me. For a while I tried an app called Wanderlist, but tapping reminders and notes into my phone makes much less of an impression on me than when I write things down. Then I forget to look at the app often enough.

Tell us how you keep track of your ideas and schedule. Do you journal? Or do you go the electronic route?

.

What Would You Tell Kids About Writing?

I attended a high school Career Day in South Carolina yesterday, to talk about writing as a possible vocation. I hosted multiple, back-to-back discussions, each one covering different writing-related careers: journalism; fiction writing; and technical writing.

I attended a high school Career Day in South Carolina yesterday, to talk about writing as a possible vocation. I hosted multiple, back-to-back discussions, each one covering different writing-related careers: journalism; fiction writing; and technical writing.

During the sessions about creative writing and being a novelist, I focused on the need to learn the craft of writing, the importance of connecting with the local writers community, and a few other things I wish I’d known when I was in high school. I was impressed by the questions the students asked. We discussed the nature of themes in novels, The use of pen names, and when/how many times to edit a working draft. I think there may have been a future writer or two in that group of bright, inquisitive students.

So, what kinds of things would you like to have known about writing, back when you were in high school?