Where does it come from?

I’m talking about that original impulse, that first bud of creativity that eventually grows into a book. Can you remember? What was it that tickled your brain and set the synapses glowing? What the very first moment when you knew you were onto something?

I’m not talking about inspiration or muses or the “need” to write. I’m trying to focus way way down to that little thing that got you going on whatever it is you are now working so hard to bring to life. What was the spark?

Normally I don’t think much about stuff from the ether like this. Especially since we here at The Kill Zone tend to focus on practical stuff like building credible characters and sturdy plot structures. But sometimes it’s fun — and maybe even a little instructive — to turn the microscope to its finest setting and examine the beginnings of life.

Every writer starts a novel from a different impulse. Some start with a situation, many by asking “what if?” Many writers are character-led. Often you can trace it back to something as small as an overheard conversation. Or an old man standing a corner glimpsed as you pass by in your car. It can be a line from a half-forgotten poem or the smell of dime store lipstick.

Sometimes that first impulse is too weak to sustain a novel. Sometimes that clot of embryonic cells never quite grows into a character. But sometimes, when you dip a bucket into the subconscious you draw up something special.

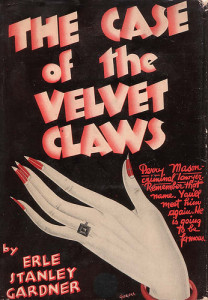

I got to thinking about this today because I was trolling the internet boning up on the history of the detective novel. I am going to be on a panel at the Edgar Symposium tomorrow that focuses on the future of the detective novel. And because I didn’t want my fellow panelists to wipe the floor with me I was, I admit, doing a little brushing up on my genre history.

That’s why I happened upon a lecture P.D. James gave in 1997 called Murder and Mystery: The Craft of the Detective Story. (Click here to read it). I’m a huge James fan; she and Georges Simenon were my guiding lights when I was trying to learn how to write detective novels. Jules Maigret and Adam Dalgliesh…those are the guys I’d want on the case when there’s a body on the slab.

So you can imagine how cool it was to read this paper of hers. It’s a great survey of the detective genre. But what I found really fascinating was the part where she talked about how she got her ideas. For James, it always starts with the setting.

I was gobsmacked when I read that. Because that’s what always gets me going. I can’t see a story until I can see the setting. Our books move between Michigan and Florida. Our settings have been, variously, an isolated island in the gulf, an abandoned insane asylum, an old family farm, a cattle pen overgrown with weeds, and an Everglades swamp way down south where the bottom of the state spreads out into the straits like a tattered flag.

Sometimes I almost feel like one of those weird psychics who claim they can see the place of death. When we are starting a new book, I can’t always tell you exactly where we are. But I can sort of feel it. And eventually the place materializes on the page, sort of like an old Polaroid.

Like right now, we working on a new Louis book that takes him back to Michigan. That’s all we knew when we started, that he had to go home. But where? Kelly insisted it had to be the Upper Peninsula (she went to college up there) and we eventually decided to take Louis as far north as we could — way up to the Keweenaw Peninsula, that strange spit of land that extends out into Lake Superior like a crooked finger pointing the way toward the Canadian wilderness. End of earth sort of idea.

But still, things weren’t gelling. There was a spark but it wasn’t catching. Then I saw a photograph someone had taken of a small abandoned cemetery. Its crumbling headstones are obscured by dense carpets of clover. It’s in the middle of nowhere. But it once the middle of somewhere — a lively town where the copper miners lived and worked in the 1800s.

P.D. James said that once she found her setting all she then had to do was begin talking to its inhabitants. Thus came her characters. So it has happened with us. We’re only ten chapters into this new book so we’re still meeting the natives, still learning their histories, still trying to develop an ear for their odd Yooper accents. (it’s somewhere between the nasal tones of Detroit and the lilt of Canada with some Finnish thrown in).

In a bit of synchronicity, I am the editor of the Edgar annual this year and months ago we decided on our theme — the sense of place in the crime novel. The essays are great — Lawrence Block on New York City, Peter Lovesey on Bath England, William Kent Kreuger on northern Minnesota, Cara Black on Paris — each writer talking about how place colors their stories.

Even as I read them it didn’t really occur to me how important setting was to me as a writer. But it is the thing from which everything else comes. If I don’t know where I am I can’t begin to tell you where my story is going. I need to know my place. It is my first spark.

What is yours?

p.s. Forgive me if I don’t respond right away but I am en route to NYC today. Will catch up when I get into Newark Airport. There’s wifi on the bus!