James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Last week’s post on publishing options drew some spirited responses, especially from one of TKZ’s erstwhile contributors. In his opinion, “self-publishing is an exercise in frustration and a path to near-assured failure for first-time authors.”

Now, I have great affection and respect for said commenter, who argues well for his point of view. But I was nonetheless discomfited by that “near-assured failure.” Been thinking about it all week. What does “failure” even mean? Who sets the standard? If a new author finds a way to make steady but not huge income, is that “failure”? If a new author keeps working and growing as a writer, is that “failure”? On the other hand, might it possibly be said that self-publishing, done consistently and skillfully, can actually lead to near-assured success? What is “success”? Is it a loyal readership, even if it pales in comparison to Dean Koontz’s (well, every readership pales in comparison to Dean Koontz’s)? Is it the happinessthat comes from writing and publishing more, faster, being in control of one’s destiny and, yes, making some money at it?

This led me to reflect, yet again, on the writers I admire most: the professionals of the old pulp days. I’ve been on record for a long time stating that this new digital age is like the pulp era, only with more opportunity and potentially better pay. But it requires a certain kind of writer. One like Erle Stanley Gardner (1889 – 1970).

Gardner is best know as the creator of Perry Mason. When he hit on that character and that formula, he was set for life. But what most people don’t know is how hard he worked to get there. He was a practicing lawyer in the 1920s, and was looking for a way to make money on the side. Writing for the exploding market in detective and crime fiction seemed promising.

He set out to do it the only way he knew how––full speed ahead. His output was, as he described it later, “man killing.” One hundred thousand words a month. A month. Over a million words a year, for at least ten years. (And much of it while he was still practicing law).

He did manage to sell some stories, but not enough to please him. Then one day he realized he did not know how to plot. His stories were merely “event combinations.” Lawyer that he was, he set out to find out how to write plots that sold (I resonate with this, because I was a practicing lawyer when I set out to learn the same thing!)

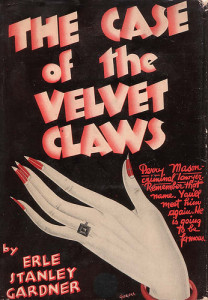

Boy, did he ever get it. And he kept up his prodigious output until he was a mainstay of famous pulps like Black Mask. Then, in 1933, came The Case of the Velvet Claws and the

introduction of Perry Mason. There was no looking back. At one time Gardner was listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the bestselling author who ever lived.

While the success that Gardner achieved is rare for writers of any stripe, his example and work ethic can be replicated today. More and more authors are doing a nice business self-pubbing. I’m not just talking about the “stars” like Hugh Howey, Bella Andre and the newest sensation, Colleen Hoover. I’m talking about people you’ve never heard of, and who don’t really mind that because they have plenty of readers who have.

1. Treat it like a job

For Gardner and other successful pulpsters, writing was a job, especially during the Depression. They had to eat. They didn’t have time to sit around the coffee bar ruminating about theories of literature. They actually had to produce stories, lots of them. They studied the markets (and wrote in popular genres, like detective and Western) and pounded the keys of their manual typewriters. Gardner was a two-finger typist and had to put adhesive tape on his tips because they would start to bleed. (This is one reason he later turned to dictating his stories, having them transcribed by a team of secretaries).

Seeing writing as a professional pursuit, Gardner reflected on his previous work in the sales field. “I had always told our salesmen that if a man had drive enough, if he kept on punching doorbells, sooner or later he would make his quota of sales. I guess the same thing applies to story writing. I know it did in my case.”

2. Treat it like a craft

When Gardner kept getting rejection slips that said “plot too thin,” he knew he had to learn how to do it. After much study he said he “began to realize that a story plot was composed of component parts, just as an automobile is.” He began to build stories, not just make them up on the fly. He made a list of parts and turned those into “plot wheels” which was a way of coming up with innumerable combinations. He was able, with this system, to come up with a complete story idea in thirty seconds.

Learning to plot stories that sell can be done, because Gardner did it, and I did it. And I wrote a book about it. It’s called Plot & Structure.

Gardner also wrote in various lengths. Successful self-publishing writers write short stories and novellasas well as full novels. Keep learning and growing as a writer.

3. Treat it like a sacrifice

There’s an old saying about the law, that it is a “jealous mistress.” To be any good as a lawyer demands time and sacrifice. Gardner knew he had to be productive to make real money, so he set a quota for himself of 5,000 words a day. If he missed a day due to a trial or other legal matter, he would make up the difference on another day.

I am often asked what the single best piece of writing advice I ever got was, and I always say, Write to a quota. I write six days a week, and take Sundays off. It’s worked for me for over twenty years. Virtually no one can write 5,000 words a day like Gardner. And of course most writers have day jobs and family responsibilities. So the key is to figure out what you can produce and commit to doing that week in and week out.

This is my standard suggestion: Figure out what you can comfortably write per week, given your particular circumstances. It doesn’t matter the number, just find it. Then up that by 10% and divide into six days. Make that your goal. Keep a record on a spreadsheet that tracks your daily writing and turns it into weekly totals. It will give you confidence to see those numbers adding up throughout the year.

Be prepared to give some things up (TV is a jealous mistress, too) in order to find time to write.

4. Treat it like a mad passion

You’ve got to be a little nuts if you want to be a professional writer. In those early years, Gardner said, “I would work until one, one-thirty or two o’clock in the morning when I would be so dog-tired that I would stop to rest and would fall asleep in the chair and have nightmares, dreaming for the most part about the characters in the story, waking up a few seconds later all confused as to what was in the story and what had been in my dream. At that time I would go to bed. I would sleep for about three hours a night, waking up around five or five-thirty in the morning. Then I would take a shower, shave, pull up my typewriter and write until it came time to go to the office.”

Now, I don’t suggest a madness of that magnitude! I find it inspiring, but also know I could never keep a schedule like that (well, maybe if I was twenty-five and unmarried . . .) But dip your quill into Gardner’s passion and scribble some of it on your writing soul. And embrace the fact that you are part of a grand fellowship of the mad, the storytellers, the weavers of dreams.

5. Treat it like an adventure right up to the end

A favorite anecdote about Gardner, when he was selling some but not enough, occurred after he felt he finally “got it” about plotting. He sent a story to Black Mask with this note: “If you have any comments on it, put them on the back of a check.” Gardner knew he had reached a place of consistent sales, was in this for the long haul, and would never stop writing.

Do you know that about yourself? Are you in this thing to the finish? Make that decision now, and you have a chance to become successful self-publishing fiction.

Gardner completed his last Perry Mason novel, The Case of the Fabulous Fake, six months before his death. Cancer caught up with him. He was hospitalized a few times. But he kept working on a non-fiction book about crime. His editor at Morrow sent him a note suggesting he might want to slow down. Gardner sent one back: “You should know Gardner by now . . . when I get enthusiastic about something, I put the whole machinery into operation.”

Erle Stanley Gardner died on March 11, 1970. He had made some autobiographical notes before his death. The last words were these: “My life is filled with color and always has been. I want adventure. I want variety. I want something to look forward to . . . The one dividend we are sure of is the opportunity to have beautiful daydreams . . . . This is as it should be. This is the color of life. I love it.”

If you want to self-publish fiction, and make some money at it, do it the Gardner way. Love life, love writing, put your “whole machinery” into action, and never shut down the operation.