Indie publishing an eBook is a lot of work. It takes creative imagination along with some technical knowledge. And, it requires a lot of commitment mixed with dogged determination and a blind belief that someone is actually going to read the stuff.

Sometimes I wonder why I subject myself to this nonsense. I’ve been indie writing eBooks for eight years now, and I’ve put twenty for-sale publications online. But, I keep at it day-in and day-out—partly thanks to a simple system of formatting eBooks from Microsoft Word.

Notice how I used the term “indie” instead of “self” publishing. That’s because I don’t publish all by myself. Rather, I have a lot of help from a proofreader, a cover artist, and a whole bunch of friendly folks who I don’t know at Amazon, Kobo, and Nook. Someday I’ll make new online friends at Apple and Google as well.

It takes money to indie publish eBooks, and there’s no getting around it. Mary, my proofreader, and Elle, my cover designer, like to get paid and they’re totally worth it. I also pay for promotions through discount email sites like Booksy (Free and Bargain), Ereader News Today, and Fussy Librarian as well as click-ads on BookBub and Amazon.

However, I don’t pay for eBook formatting services which could run $100.00 or more for a proper and professional product (not a ten-buck Fiver special). Doing the math… at a $2.00 royalty that’d be at least 50 sales to break even on formatting costs. Besides, I’ve found the formatting process to be one of the best self-editing tools out there.

I know many writers detest using a PC infested with Word. They’d rather use a tool like Scrivener or their Mac equipped with Vellum. That’s fine, but I’m sticking with what I know, and I’d like to share my top ten tips for formatting eBooks from MS Word.

Tip #1 — Understand What eBooks Really Are

This sounds basic, and it is. If you look up “eBook” in the dictionary, you’ll find it’s a noun meaning “a book composed in, or converted to, digital format for display on a computer screen or handheld device.” An eBook is really a collection of digital characters forming a readable document.

There are two main eBook types. The most popular format is a Standard eBook that uses real-time, flowable text where the end-user can make personal changes to features like font type and size (settings). There are no page numbers (pagation) on standard eBooks because the total page numbers change according to the user’s size preference. Most novels are formatted as standard eBooks so they can be conveniently read on all types of devices like eReaders, desktops, laptops, and smartphones.

There are two main eBook types. The most popular format is a Standard eBook that uses real-time, flowable text where the end-user can make personal changes to features like font type and size (settings). There are no page numbers (pagation) on standard eBooks because the total page numbers change according to the user’s size preference. Most novels are formatted as standard eBooks so they can be conveniently read on all types of devices like eReaders, desktops, laptops, and smartphones.

The other format is a fixed-layout eBook. These are popular for graphic-laden publications with images, graphs, tables, and charts where the material size can’t be changed. The graphics won’t “flow” across the page if you change settings but you can zoom in and out. Fixed-layout eBooks are popular with publications like cookbooks, children’s books, comic books, graphic novels, and educational textbooks.

Typically, you’d format a standard eBook for:

- Publications with mostly continuous text

- Works with small images embedded between paragraphs

- Ensuring maximum usability on smaller devices like smartphones

Non-typically, you’d format a fixed-layout eBook for:

- Preserving text over images

- Wrapping text around images

- Setting background colors

- Using multi-columns or horizontal orientation

Tip #2 — Know the eBook File Types

There are over twenty eBook file types. By file type, I mean the software they’re written in. There is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to eBook formatting. However, as far as I know, you can convert a Microsoft Word document into any file type.

It’s important to know why there are so many eBook file types. It’s called technical evolution and business strategies. Some might call it money.

The eBook concept has been around a long time. Back in the 1930s, a guy by the name of Bob Brown got the idea of a “readie” after watching a “movie”. As Bob put it, “A simple machine which I can carry or move around, attach to any old electric light bulb, and read hundred-thousand word novels in ten minutes if I want to, and I want to.”

Bob was a little ahead of his time, but Michael S. Hart wasn’t. Hart is credited with inventing the first true eBook file type in 1971 when he worked as an engineer for Xerox in Illinois. He demonstrated his patent by typing the US Declaration of Independence into a digital file so it flashed up on a TV screen.

Sony upended Hart in 1990 with its Data Discman eBook player. So did Steven King. In 2000, King released the first true indie eBook with Riding The Bullet that was exclusive to online readers. It was downloaded 500,000 times in 48 hours.

And, along came Amazon. The ’Zon bought Mobipocket in 2005 and turned that eBook file technology into proprietary software exclusive to their Kindle eReader. I’m sure they intended to corner as much of the market as they could by allowing Amazon-published eBook files to be read only on Amazon-sold devices. Seems to me they did a good job of it.

And, along came Amazon. The ’Zon bought Mobipocket in 2005 and turned that eBook file technology into proprietary software exclusive to their Kindle eReader. I’m sure they intended to corner as much of the market as they could by allowing Amazon-published eBook files to be read only on Amazon-sold devices. Seems to me they did a good job of it.

That brings me to the three most popular eBook file types today—although there are over twenty in existence. All three file types have their own formatting quirks and quarks which a conversion software like Calibre looks after for you. All three files nicely work with a Word.doc… providing your format the Word.doc properly in the first place. The three main eBook file types are:

Amazon Mobi — This file is exclusive to Amazon and is also known as MobiAZW or .azw. Mobi files only read on an Amazon device like a Kindle or Kindle Fire. You can’t load a Mobi file on a regular reader like a Kobo or Nook, nor on an Apple product or in Google play. Don’t worry about how a Mobi file works. All you need to know is it’s picky about how you prepare a Word.doc for it.

EPub — This acronym stands for electronic publication, and it was uniformly endorsed by an outfit called the International Digital Publishing Forum in 2007 to replace the older Open eBook file system. EPub is used exclusive of Amazon, and you can’t load an EPub file on a Kindle. Apparently, an Amazon black hole will open up and swallow you if you try. So, if you plan on “going wide” and publish on non-Amazon forums like Kobo, Nook, Apple, and Google, you’ll have to format your Word.doc as an EPub file.

Adobe PDF — Here we have the difficult child in the eBook file family. A Portable Document File is technically an electronic book, but some electronic publishers make it sit in the corner. PDF’s are great as technical eBooks that you can share online or use as an email list magnet, but they aren’t compatible files for commercial eBook sites. And, whatever you do, do not try to upload a PDF to a retailer in place of a properly-formatted Mobi or EPub file. It will turn into a mess.

Tip #3 — Appreciate How a Microsoft Word Document Works

Let me say that I’m not an expert on MS Word. Not by any means. I’ve written millions of words in this software program, but there’s a lot I don’t know about it. However, I know enough about Word to get it to do pretty much what I need it to, and I’m comfortable with that.

Microsoft Word is a word processing program. It’s the gold standard when it comes to managing text documents, and it’s used professionally and recreationally by over a billion people. No word processing tool even comes close to Word for popularity.

In 1981, Microsoft bought an existing processing program called Bravo. They had a top engineering team re-invent Bravo which they released as the Multi-Tool Word for Xenix Systems. It was meant to compete with WordPerfect which was the leader at that time, and its name was soon shortened to Word.

In 1981, Microsoft bought an existing processing program called Bravo. They had a top engineering team re-invent Bravo which they released as the Multi-Tool Word for Xenix Systems. It was meant to compete with WordPerfect which was the leader at that time, and its name was soon shortened to Word.

Word has been renovated many times over the past four decades. I use Word 2010 because I’m a Luddite and too cheap to upgrade to the new Word 2019. For eBook writing and formatting, my Word version works fine and I’m sticking with it on Windows 8.

Word wasn’t very popular at first. It was clunky and troublesome with a big learning curve. That changed as Word became more WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) and allowed users to customize their documents and view on-screen what the end product would look like.

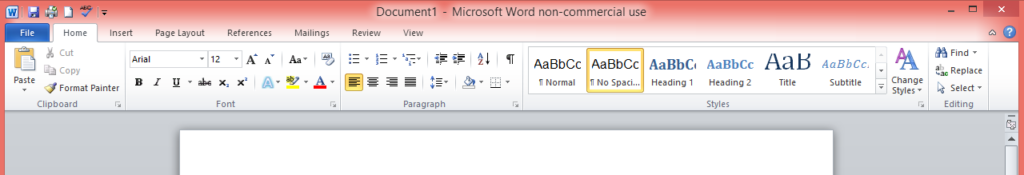

My Word 2010 has eight tabs on the upper toolbar. I use five of them daily—file, home, insert, page layout, and review. The other three—references, mailings, and view—are there if needed.

MS Word has some marvelous shortcuts. They are real time-savers and can resuscitate an accidentally-erased page part or an entire document at the press of two keys. Here are the shortcuts I regularly use:

- Control + A highlights the entire document

- Control + C copies the highlighted portion

- Control + F opens a search bar

- Control + K opens a hyperlink window

- Control + V pastes a copied piece of text

- Control + X cuts a highlighted portion

- Control + Z restores a delete

The Control + Z feature has gotten me out of more writing, editing, and formatting pickles than I can remember. Thank God the MS engineers built this into their Word software. It also transports with a Word.doc when you transfer it into an eBook formatting tool like Calibre.

Tip #4 — Become Very Familiar with Your MS Word Home Tab

Your home tab is the main tool belt for Word. Most features that you need to write an eBook are right there at your fingertips. Let’s go through the main tools and discuss what works best for drafting a Word document that easily formats or converts into a Mobi and EPub file

Font Face — Depending on the Word version you’re working in, you’ll have dozens and dozens of font styles to choose from. There are hundreds more available to download from the net. That’s all fine and well to get fancy on your Word doc, but that’s not okay when you go to format your eBook. No matter what font face you pick, Amazon’s Mobi proprietary software is going to output your font in a fixed serif style so you might as well use Times New Roman right off the bat. EPub platforms are a bit more font-friendly so you can use a serif style like Adobe Garamond or a sans serif typeface like Ariel.

Font Size — The nature of eBook operation is that the reader can modify their on-screen font size to suit their pleasure. However, keep your Word doc as clean and uniform as you can. I recommend that titles go in 24 point, introductions in 16 point, chapter headings in 14 point, and all text in 12 point. Do not use a font size larger or smaller than 12 for your main text body or you’ll regret it.

Bold, Italics & Underline — Both Mobi and EPub files will import hidden html code from Word that specializes your font accents like bold, italics, and underlines. They’ll convert from Word to an eBook file without having to identify strange-looking html symbols like <b>, </b>, <i>, </i>, <u>, </u>, etc.

Font Color — There’s no problem using a colored font in Word and having it formatted on either main eBook file. I’d strongly suggest keeping your font in standard black which should be your default font color. Deep reds or blues are nice to make a point but don’t even think about using any color except white for your background shading. It will not convert.

Bullets and Numbering — Also, there’s no problem getting automatic list numbering and billeting to convert from Word to an eBook file. It’s not like WordPress which has a hissy-fit if you try to import something creative.

Align Text — You should use align left for the vast majority of your document text. If you need to make a point with a scene break or something requiring a center text, that will show up fine on an eReader, too. Avoid using align right because it reads really weird on an eScreen.

Justify — Word lets you set your text with evenly aligned or justified left and right margins. That causes your words to stagger in spacing which looks crisp and clean on a Word screen. However, when you format a justified document into an eBook file it can look messy on an eReader. Do yourself a favor and don’t format your Word document with a Control + J justification. When a reader enlarges the font on their device, there will be ugly gaps in the word spacing.

Line and Paragraph Spacing — Use 1.15. That’s it. 1.15 only.

Style Boxes — Use the Normal setting for all text and Heading 1 for anything you want to appear in your table of contents (TOC). Set your style default to the font face, size, and color you want and leave it there. It’ll save a lot of formatting time. Ignore the No Spacing, Heading 2, Title, and Subtitle style boxes.

Find & Replace — This feature is irrelevant to formatting, but it sure makes your writing and editing life easier.

Tip #5 — Be Careful with Indents and Paragraphs

If there’s one area that could get you into a maximum-security eBook formatting prison, it’s screwing up indent and paragraph formatting on your Word document. I can’t stress this enough!!!

Most writers probably use the enter and tab keys for paragraph spacing and indenting the first line. This looks good on a Word doc and a PDF, but it’ll be a pile of doggy-doo when you see it on a Mobi or EPub file.

I do eBook formatting for friends, and I see this error repeatedly. To fix it, the Word doc has to be exorcised of this formatting demon. This is a big job if you try to fix this manually. The trick is to highlight the entire document and use the Find/Replace feature. You enter ^t in the Find field, put nothing in the Replace field, and click Replace All. It will reset your Word doc to a neutral format so you can properly rework it as Mobi and EPub compatible.

What you have to do (if you want industry-standard eBook formatting for paragraph indents and spacing) is to use the tiny little “paragraph” feature on the bottom center of the Word toolbar. Click on the enlarge icon which, at my age, you need glasses to see.

The paragraph window opens and offers you options for indents and spacing as well as line and page breaks. Do this:

- Alignment — set on “left”

- Indentation — set left and right at “0” (zero)

- Special — set as “first line” (this is probably the most important eBook formatting tip)

- Spacing — set before and after at “0” (zero)

- Line Spacing — set at “single” (your main toolbar setting at 1.15 will override)

- Line and Page Breaks – leave at the Word default setting (more on this coming up)

Terry Odell did a great piece on yesterday’s Kill Zone titled Ins and Outs of Indie Publishing: Going Wide. Terry nailed it with this advice on formatting, “Some basics are formatting in TNR, 12 point font, 1 inch margins all around, and use a paragraph style for indenting, NOT TABS. EVER.”

Tip #6 — Use Show and Hide

This MS Word feature is an absolute godsend to eBook formatters. It’s truly lifesaving. This is the show and hide symbol: ¶ It’s right up there at the center of your Word toolbar to the left of the style boxes. At least it’s there on Word 2010. I’m not sure about other versions, but I’m sure it’s not discontinued.

Show and Hide (¶) lets you view your Word doc behind the scenes. It allows you to check spacing, indents, font size, and little things like hidden bold, italics, and underline specialties that lie between lines and paragraphs. ¶ lets you adjust your entire document for uniformity. There will be non-conforming information in your document that you can’t see on a Word screen but will confuse the eBook conversion/formatting and it can become real dog-vom when it shows up as a Kindle, Kobo, Nook, Apple, or Google eFile.

Tip #7 — Be Careful With Page Breaks but Promote Page Layout

By design, eBooks are fluid and non-editable. Although there’s no way for an outside party to enable editing on a published eBook, the reader has total control over using their eReader in a personal manner. They can adjust all sorts of reading conditions from size to lighting, but they can’t modify the content.

That includes page breaks. You, as the writer in Word and the formatting in EPub or Mobi have total control on how you want to interrupt your reader’s flow. Be aware that they might not like pre-assigned page breaks. However, they’ll hate an eBook that isn’t properly formatted for page layout.

There are two schools of thought about placing page breaks into a Word doc destined for an eBook file. One is to leave page breaks out altogether and let the eFile software run the show. The other is to strategically place page breaks where they work to help the eFile, not hinder it.

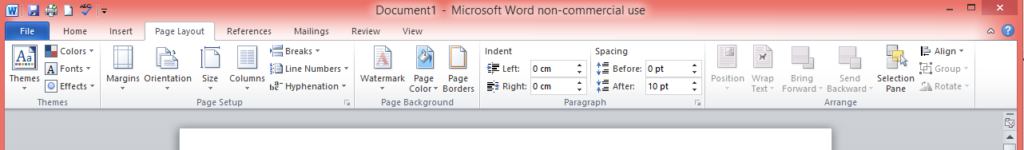

The page break feature on Word is in the Page Layout tab at the top left third space, and it’s called “Breaks”. If you click on it, you’ll see a lot of options to stay away from. If you must use a page break, just put your cursor on the next paragraph indent and click “page”. You’ll see a line that interrupts your Word text and starts a new page. It does the same on an eFile.

Use page breaks sparingly. The beauty in an eReader is experiencing a continuous flow and a page break can take the reader right out of the book. I don’t place page breaks between chapters. The only place I put a page break is when I add a graphic like an inserted picture. The page break ensures the insert will show up as a whole on a screen and not be cut off.

There are two more highly-important features in Page Layout and you need to set them like this:

- Indent Left: 0 cm

- Indent Right: 0 cm

- Spacing Before: 0 pt

- Spacing After: 0 pt

Your left and right margins are likely set by default at 1 inch or 2.54 cm. If they are, leave them there. If not, make them your standard Word doc default setting. The reason you put paragraph spacing at 0 pt before and after is so you can manually set them with your spacer or enter bar when you review your document with the ¶ feature. If you have a mixture of automatic spacing and manual, your eFile format will be messed up.

Tip #8 — Insert Images that Don’t Get Messed Up

To eBook file credit, they’re image friendly. To their discredit, they’re quite picky about formatting from a Word document. With eBook formatting from MS Word, you can’t eat your cake and still have it too.

Like another activity, size matters in eBook formatting. Here’s the #1 rule when formatting images in a Word doc. Don’t do it.

Instead, prepare your images in another software form and save it as a jpg or png file. Once you have it eBook compatible, then use the Word Insert tab to paste the image where you want it in the Word doc. Mini-tip: Insert the image using the center align feature on the toolbar – not the justify one.

I use good old Paint to format an image headed for an eBook. I take a screenshot or download an internet-based jpeg or png and upload it to Paint. Then, I crop the image and size it to 500 pixels wide by whatever height works. I “save as” and then insert it into the Word doc. It then stays stable as an eBook image at a manageable 500 pixel-wide size despite what an end-user might do with setting changes on their reading device.

If you try to size images within Word, they’ll do what they want as an eFile and the professionalism of your formatting will be compromised. Remember the KISS principle (Keep It Simple Stupid). There’s no need to complicate eBook image formatting as long as you import a pre-formatted image into Word before converting to an eFile like Mobi or EPub.

Tip #9 — Use Calibre for Formatting Word to Mobi or EPub

Like Word, I don’t profess to be a Calibre guru. In fact, the more I use Calibre as an eBook formatting/conversion tool, the more I KISS. Calibre can have a big learning curve if you want to know the geek stuff.

I don’t. I only want to write an eBook in Word, format/convert it into a Mobi or Epub file, and put the product up for sale on a retail platform. I don’t care about how the things work. You can download free software for Calibre here.

Don’t be intimidated by Calibre. It’s an eBook conversion software system designed like a pipeline. Schematically, here’s how it works:

- Step 1 — Input Word doc format

- Step 2 — Input Calibre Plugin (Mobi or EPub template)

- Step 3 — Transform

- Step 4 — Output Plugin (Mobi or EPub finished file)

- Step 5 — Save eFile to your hard drive and/or flash drive

- Step 6 — Upload your eFile to your eBook retailer’s dashboard

Functionally, here are the simple steps to convert a Word document into an eFile on Calibre:

- Step 1 — Open Calibre

- Step 2 — Click Add Books

- Step 3 — Upload your Word.docx

- Step 4 — Click Enter Metadata (you can leave this blank and move on)

- Step 5 — Click OK

- Step 6 — Verify Input Format is DOCX and set Output Format (you have a choice that includes EPUB and MOBI. AZW3 is also there, but just use MOBI for Amazon)

- Step 7 — Click OK (the JOBS icon circles in the lower right. When it stops, you’re done)

- Step 8 — Slick SAVE TO DISC and select the folder on your computer.

It’s now saved as formatted eFile that’s ready to put up for sale on a retail eBook site. There are a lot more things you can try on Calibre but if you KISS, that’s all you have to do. Note: You have to repeat the process for each eFile conversion.

That’s it. Formatting a Word document to an eBook is this straightforward. The trick is making sure your Word doc is eBook friendly. I can’t emphasize this enough!!! Oh, BTW, save your Word document as a Word.docx. It’s the most recent form and it’s compressed with less chance of being digitally compromised.

Side Note: Amazon now allows you to directly upload a Word.docx to KDP, and their system will automatically convert it to a Mobi/AZW file. I’ve tried it and it wasn’t pretty. However, I’ve uploaded a Word.docx to Kobo and it came out great. You can also use an eBook aggregator like Draft2Digital or Smashwords to format your Word document, but they’ll take a 10% cut for their service. Again — the real trick is to make sure your Word.docx is properly set up before converting it to an eFile.

Tip #10 — Have Fun & Make Money

I have no ethical problem about making money from turning Word docs into eBooks. However, actually making money this way is an art on its own and when I find the secret I’ll gladly share it. For now, though, I’m having fun doing this.

How about you Kill Zoners? What’s your experience with MS Word and formatting eBooks? Please share what you know or ask what you don’t know.

——

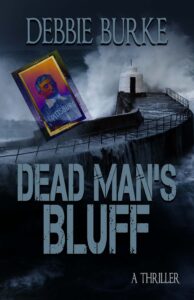

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and forensic coroner. Now, he’s a struggling indie publisher who writes crime stories on Word, formats them on Calibre, and flogs them on Amazon, Kobo, and Nook.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and forensic coroner. Now, he’s a struggling indie publisher who writes crime stories on Word, formats them on Calibre, and flogs them on Amazon, Kobo, and Nook.

Garry lives on Vancouver Island in British Columbia on Canada’s west coast. When not writing, Garry Rodgers spends his time putting around the saltwater and hiding from the taxman.