by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

A case can be made that the greatest movie star of all time, the GOAT if you will, is Bette Davis. In a career spanning 50 years she never gave a bad performance, even in guest roles on TV shows like Gunsmoke and Wagon Train. That’s because acting was her life and she never wanted to give the audience short shrift.

A case can be made that the greatest movie star of all time, the GOAT if you will, is Bette Davis. In a career spanning 50 years she never gave a bad performance, even in guest roles on TV shows like Gunsmoke and Wagon Train. That’s because acting was her life and she never wanted to give the audience short shrift.

She’ll forever be known for one of the few truly iconic performances in the movies, along the lines of Bogart in Casablanca, Gable in Gone With the Wind, and Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire. That is the role of Margot Channing in All About Eve. (“Fasten your seatbelts. It’s going to be a bumpy night.”)

Today I want to bring up a classic Davis “woman’s picture” (as they were called in WWII, to cater to all the women whose men were off fighting a war), Now, Voyager. As always, I encourage you to watch it, then refer back to these notes for craft study.

Today I want to bring up a classic Davis “woman’s picture” (as they were called in WWII, to cater to all the women whose men were off fighting a war), Now, Voyager. As always, I encourage you to watch it, then refer back to these notes for craft study.

The plot concerns Charlotte Vale, the dowdy daughter of a rich, domineering Boston matriarch. She’s been driven to neuroses by her mother, who long ago decided Charlotte was too ugly and untalented to flourish in society.

**Spoilers Ahead**

Sympathy for the Lead

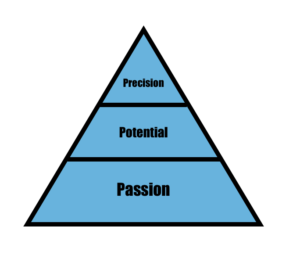

The first task of the writer is to get the reader connected to a Lead character. There is no plot without character; there is also no character without plot. A plot is the record of how a character, through strength of will, struggles against death (physical, professional, or psychological). Thus, the death struggle reveals the true character underneath.

When the Lead is an underdog, facing hardship and long odds, we get the sympathy factor. That is the emotional connection that bonds reader and character and makes the reader want to follow the story to see how it all turns out.

Disturbance

Don’t waste precious fiction real estate by having a character on page 1 just sitting around, thinking or feeling or flashbacking. Stir the waters somehow. Portend trouble.

At the beginning of Now, Voyager, we meet the homely, timid Charlotte Vale. She is in the final stages of a nervous breakdown, though her haughty mother (Gladys Cooper) is in denial about it.

Charlotte is contrasted with her niece June—a rich, pretty, outgoing social butterfly (Bonita Granville). June’s mother Lisa (Ilka Chase) has asked her psychiatrist, Dr. Jaquith (Claude Raines) to come to the Vale home for tea. When June teases Charlotte mercilessly, Charlotte loses it, lashes out, runs upstairs. Dr. Jaquith tells them Charlotte needs to spend a few weeks at his sanitarium in the mountains.

The rest gets Charlotte to a point where Dr. Jaquith believes she’s ready to take a step of faith (in herself; psychological death is at stake here. Will Charlotte ever become a new and better self? Or will she remain the “dead” daughter of a heartless mother?)

Dr. Jaquith approves Lisa’s idea that Charlotte take an ocean cruise. He gives her a book of Whitman poetry in which he has inscribed the line Now voyager, sail thou forth to seek and find.

Thus, in introducing your Lead, consider:

Imminent Trouble. If there is a physical or emotional threat happening during the opening, readers are immediately drawn in. Certainly Charlotte is suffering emotional threat.

Hardship. What physical or psychological hardship might your character suffer from? This should be something not of their own making. Charlotte has been a true victim all her life.

Underdog. Readers love underdogs. How might your character face long odds? Charlotte’s age, profile and home life are not promising for a personality makeover.

Vulnerability. When Charlotte goes on the cruise, we know she is emotionally vulnerable. The slightest misstep could send her back to the sanitarium.

Indeed, a misstep like that is about to happen to Charlotte on the ship, until…

Doorway of No Return

At the ¼ mark of the film, a handsome man unobtrusively helps Charlotte out of an embarrassing situation. The man is Jerry Durrance (Paul Henreid, who played Victor Laszlo in Casablanca). This is the emotional Doorway that sets the rest of the plot in motion—they fall in love.

Unfortunately, Jerry is married. There’s your plot.

They know they must part. At the final goodbye on the ship, Jerry gives Charlotte a bouquet of camellias to remember him by.

The Mirror Moment

What is this movie really all about? What is your novel really all about? You can find (or construct) the answer with the “mirror moment.”

Charlotte finally comes home to face her mother. And boy, does the mother try to smash Charlotte right back to where she was before.

This is the mirror moment for Charlotte. It’s where it should be, at the exact halfway point of the movie. She is thinking, Can I possibly stand up to my mother for the first time? If the past is any indication, I’m probably going to die (psychologically). Must I go back to being the old Charlotte again?

If only there was something to give her the courage to stand up for herself. Often, this courage is inspired by a physical item introduced earlier in the story, carrying with it emotional power. Like this:

Camellias! This emotional memory is enough to give Charlotte the courage to stand up to her mother. (And did you notice the actual mirror in the scene?)

Can Charlotte complete the transformation? What about Jerry and his unhappy marriage? What about the counter-attack by her mother?

Well…watch the movie! Treat yourself to one of the great film performances.

And you, writer, like Charlotte, take a step of faith with your writing. Stretch. Risk. This epigraph is meant for you, too: Now voyager, sail thou forth to seek and find.

Comments and questions welcome.

One other note about Bette Davis. Like Bogart, you’ll almost always find her smoking her way through a movie. But here’s the difference. Davis always puffs on her cigarette in a way that is in keeping with emotional tone of the scene. It’s actually a wonder to behold, the way she uses what other actors treat as a throwaway prop. That’s why she is the GOAT.

Today marks the 20th anniversary of

Today marks the 20th anniversary of

There was a hit song back in the 70s called “Torn Between Two Lovers” (not to be confused with the Hannibal Lecter hit, “Torn Between Two Livers”).

There was a hit song back in the 70s called “Torn Between Two Lovers” (not to be confused with the Hannibal Lecter hit, “Torn Between Two Livers”).

“I’m completely library educated. I’ve never been to college. I went down to the library when I was in grade school in Waukegan, and in high school in Los Angeles, and spent long days every summer in the library… I discovered me in the library. I went to find me in the library. Before I fell in love with libraries, I was just a six-year-old boy. The library fueled all of my curiosities, from dinosaurs to ancient Egypt.” — Ray Bradbury

“I’m completely library educated. I’ve never been to college. I went down to the library when I was in grade school in Waukegan, and in high school in Los Angeles, and spent long days every summer in the library… I discovered me in the library. I went to find me in the library. Before I fell in love with libraries, I was just a six-year-old boy. The library fueled all of my curiosities, from dinosaurs to ancient Egypt.” — Ray Bradbury One of my college roommates, Rick, got a bike. One day I asked him if I could try it. He showed me the basics of clutch and throttle. No problem. At the time I was driving my dad’s old three-on-the-tree Ford Maverick. I knew the drill.

One of my college roommates, Rick, got a bike. One day I asked him if I could try it. He showed me the basics of clutch and throttle. No problem. At the time I was driving my dad’s old three-on-the-tree Ford Maverick. I knew the drill.