Monthly Archives: January 2014

First page critique: QUEST FOR HONOR

by Joe Moore

Today’s first-page critique is from a story called QUEST FOR HONOR. My comments follow.

July 2011

Somalia

Every night, he saw the children. No matter how tired he was, no matter how preoccupied he was from the events of the day, no matter anything, he dreamed. And in his dreams, they came for him. Their eyes were filled with pain and supplication, and behind them was always a shadow, looming in the back, dark and menacing, and sometimes he could hear its wicked laughter, smell its fetid breath.

On this hot night, he woke up screaming. “No! Save them! Save them!” Bolting upright suddenly, the bedclothes fell away from him, drenched with his sweat. He was panting. The shadow had gotten close to him, as the children milled around, and he felt its cold tendrils snaking around him, drawing him closer…

There was a knock at the door, then a muffled voice.

“Yusuf! Are you all right?”

He didn’t answer, and the door edged open. The face that peered in was that of Amir, his most trusted lieutenant. Did the man never sleep? “Are you ill, Yusuf? May I get you anything?”

In his bed, the man shook his head, banishing the last wisps of the faces, knowing they would be back, perhaps as soon as he nodded off again. “Thank you, Amir, but I am fine. A bad dream, that is all.”

“Shall I prepare some hot tea? It often helps me sleep.”

Yusuf started to object, but said, “That would be good. Please, bring it to the library, and join me.”

He rose and pulled on a dry robe, switching on the light. The lone overhead bulb sputtered but stayed on. At least the electricity was running, he thought. Otherwise it would be candles and lanterns, as it was some nights. How could this truly be part of the land of Allah’s people if it could not consistently provide even the bare necessities? Ah, but what necessities are we thinking of, Yusuf reminded himself. The ones you enjoyed back in America, at university? Or the ones the true believers scraped and scavenged for every day, here in the barren countryside, the crowded cities, that made up the lands of the Prophet, blessings be upon him?

I’m not a big fan of opening a book with a dream, but this does set the stage for drama. The writer has a good command of storytelling. I have a suspicion that this is going to be an emotionally charged tale. There’s not much I find to critique here. Some unneeded use of adverbs and extra wording. A bit of cleanup can cure that. But overall, a good start. Here are a few suggested line edits.

Avoid passive voice. Change “Their eyes were filled with pain and supplication…” to “Pain and supplication filled their eyes…” Change “…and behind them was always a shadow, looming in the back, dark and menacing…” to “a shadow, dark and menacing, loomed behind them…”

Avoid run-on sentences. “Their eyes were filled with pain and supplication, and behind them was always a shadow, looming in the back, dark and menacing, and sometimes he could hear its wicked laughter, smell its fetid breath.” to “Pain and supplication filled their eyes, and a shadow, dark and menacing, loomed behind them. Sometimes he heard its wicked laughter, smelled its fetid breath.”

Avoid adverbs and unneeded words. For example: “Bolting upright suddenly, the his bedclothes fell away from him…”

Avoid confusion. “Did the man never sleep?” is Yusuf’s interior thought yet the reader might feel it is Amir who thinks it. Place it in italics. Then start a new paragraph with “Are you ill, Yusuf?”

Avoid unneeded words. Change “In his bed, the man shook his…” to “Yusuf shook his head…” We already know he is in bed.

Avoid simultaneous actions that are not simultaneous. Change “He rose and pulled on a dry robe, switching on the light.” to “He rose, pulled on a dry robe, and switched on the light.”

I think this is a good first draft. A little editing would make it tight and crisp. I would definitely keep reading. Thanks to the author for submitting this first-page sample. Good luck.

How about you guys? Would you turn to page 2 or move on?

Racing Toward the Finale

As you near the finish line for your Work in Progress, the tendency is to speed things up. You can’t wait to be done and take a break. You’re tired of the story and want to end it already. Or you’re approaching your deadline and have to finish in a hurry.

And yet this is when you need to slow down and let the finale unfold in exquisite detail. Haven’t you watched a TV show that ties up all the loose ends in the final two minutes? How annoyed does that make you feel? As for a book series, fans of Harry Potter felt frustrated by the brief epilogue. They wanted more explanations of what would happen to the characters in life beyond the book. So slow down when you approach completion.

The heroine’s confrontation with the villain should reveal every heartbeat, every pulse-pounding moment of fear. This is when you want time to slow so you can catch every nuance. Yes, the pacing must be quick, but you shouldn’t cheat the reader out of emotional reactions, either during the scene or afterward. And the fight sequence, if there is one, shouldn’t be rushed.

What about when the villain has been defeated? I always like to have a Wrap Scene where quiet reflections on lessons learned, a review of events, and/or a self-revelation occurs. This is where you tie up loose ends and perhaps frame the story with the same people or setting as the opening sequence. Make sure your readers go away with a sense of satisfaction.

Putting some distance between yourself and your work will help you gain perspective. Go back after two weeks, if you have that luxury, and read the ending again. Flesh out any spots that are sparse and be sure you’ve covered all the bases. Your finale will dictate what impression readers take away when they close the book.

Do you tend to race ahead when you’re approaching the finish line?

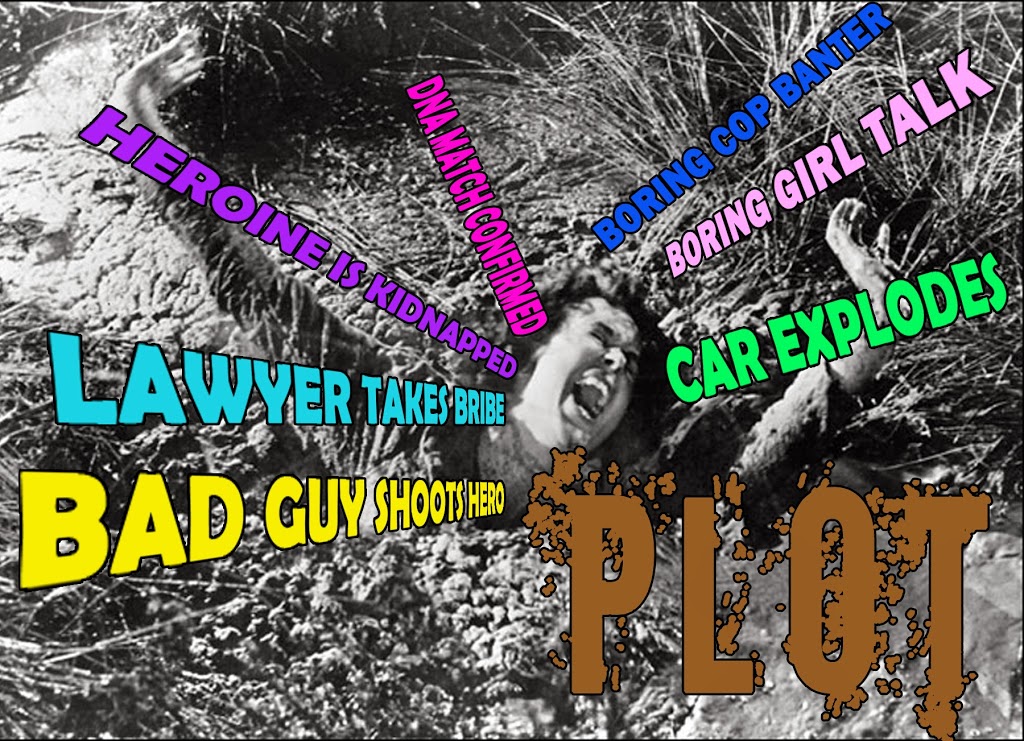

The Muddy Middle: Where good plots go to die

The classic dramatic plot

Recently, I re-read Gone with the Wind. It clocks in at 63 chapters. The first five are what I’d call the opening and the story essentially wraps up in one chapter. So what did Margaret Mitchell fill the 57 chapters in between with? Challenges, obstacles, reversals of fortune for her characters, especially for Scarlett O’Hara. This is the essence of plotting, what keeps the story from bogging down. And it has a definite trajectory. A good plot is like Woody Allen’s shark — if it’s not constantly moving forward — and upward — it dies. (Warning: more shark analogies ahead!)

Let me give you a visual. Which of these plot lines is the best?

The one at top left is a flat line. If you’ve got one of these you’re in big trouble. (Or maybe writing bad literary fiction…sorry, cheap shot). That one below it is almost as bad, a plot that is a yawner until the writer gives you a paddle-jolt climax that comes out of nowhere. The one at top right looks like it would be a nifty thriller — nonstop action! — but it also doesn’t work because the pacing is too frenetic. Think about a roller coaster. Why do people love them? Because the heart-stopping plunges are balanced with quiet moments when we can catch our breath and anticipate the next thrill. And that leaves us with the jagged plot line at the bottom.

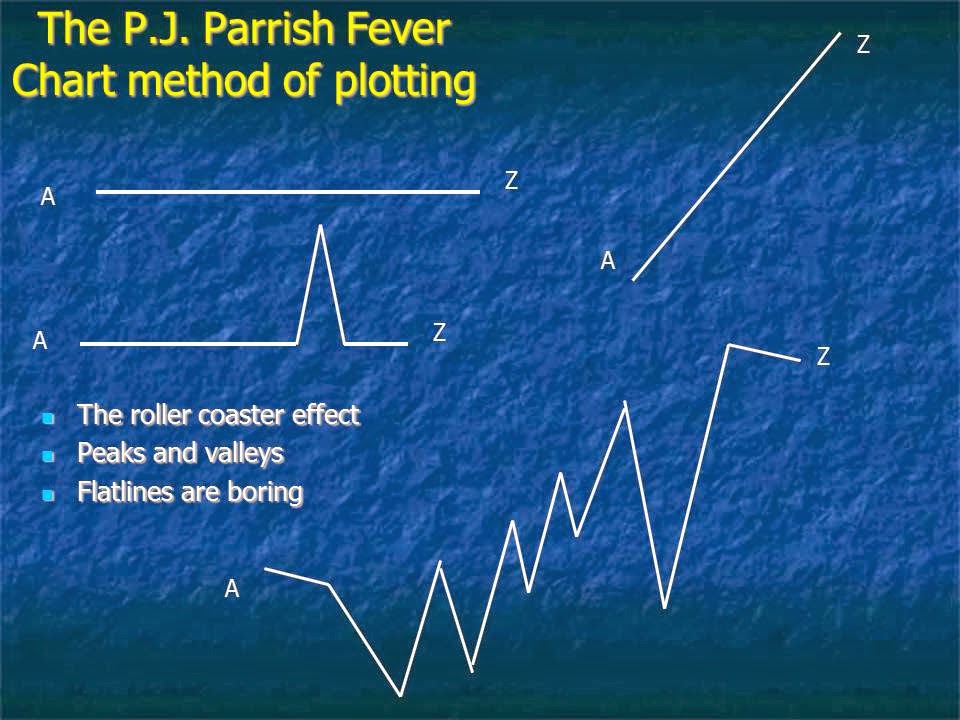

You give me fever!

I call it The Fever Chart Plot because it is graph that charts the protagonist’s fortunes. The trajectory of the story moves forward AND always upward toward the climax but between A and Z it and dips and rises. The beginning A represents an attention-grabbing opening scene. Then there’s a slight dip as we establish characters and setting and define the problem (in crime fiction, usually a murder to be solved). The line dips because as the problem is more clearly defined, it seems increasingly unlikely the hero will ever solve it.

But then the line goes up as the hero begins to cope, fighting his way through a thicket of complications. Sometimes, the plot hits an early high because it looks like the hero has things in hand but then there is a dip — something goes wrong, there is a reversal of fortune. The hero climbs out again only to be confronted with new obstacles along the way. We get another hard climb and more dips. Eventually, the hero achieves a summit of sorts (toward the end) when it looks like he will be triumph BUT…

He is plunged into a final abyss of despair (the last major setback before the climax). This is where your classic tragic plot usually ends. (Hamlet dies). But we’re talking heroic plots here, so just when it looks like all is lost, the hero, through bravery, smarts and fortitude, recovers and soars back, solving the problem once and for all. That little line at the end? That’s just the denouement where little threads are tied up.

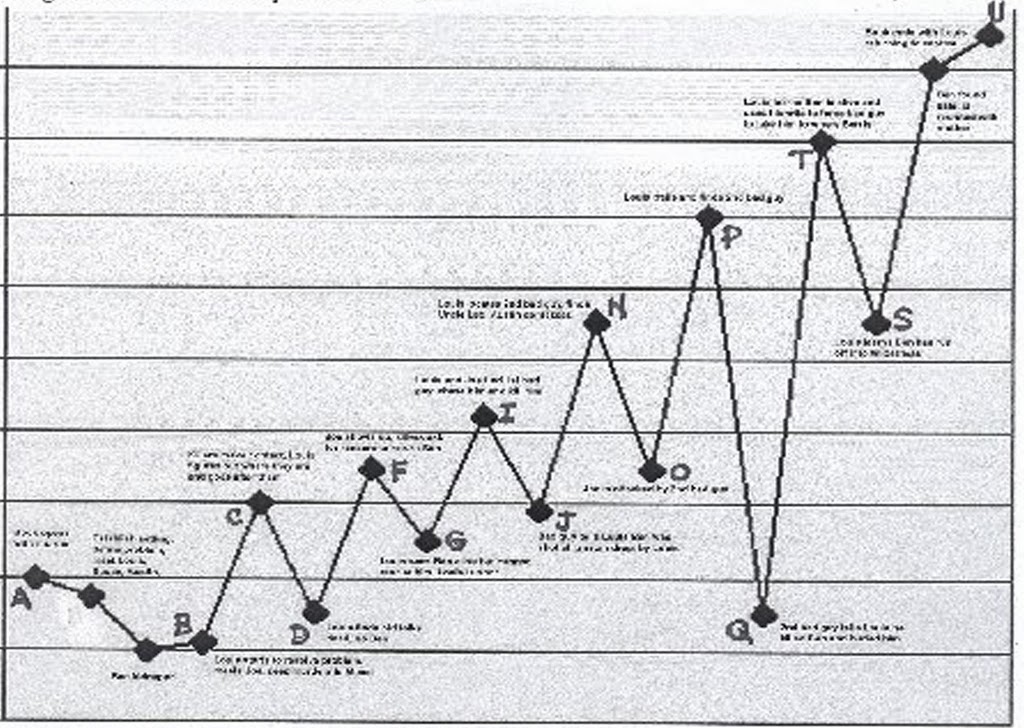

This might seem obvious almost to the point of simple-mindedness, but it is the sturdy scaffolding on which most mysteries and thrillers are built. Your book might have fewer or more dips and rises, depending on the complexity of your story. I once charted out all the plot points of our book A Killing Rain and this is what it looks like:

Tools to dig out of the Muddy Middle

- Setbacks

- Pendulum swings of emotion

- Raising the stakes

- Obstacles

- Rift in the team

- Isolation of the hero

The Amity mayor who’s hellbent on saving the island’s lucrative July Fourth weekend. Brody’s overruled, the beaches stay open and all Brody can do is sit on the beach and sweat. We get a slight rise in the plot graph when Hooper and Brody go out on a night hunt (Hooper is a perfect foil character for Brody, there to give him hope and pull him out of the dips). But then they find that dead guy in the submerged boat and things look increasingly grim. Until we get a major up-thrust for Brody. He gets the money to hire a professional shark hunter — Quint.

Our hero has things under control now, right? Not so fast. Quint is a great character, and he represents one of the most effective devices you can use to beef up your middle — THE RIFT IN THE TEAM. As the three men hunt the shark, the escalating tension between them threatens the quest. You see this device used a lot in cop novels — the errant hard-drinking guy bumping heads with his partner. Think of every partner Dirty Harry ever had. Or watch the sparring between Woody Harrelson and Matthew McConaughey in HBO’s True Detective. Rifts in the team. Brody is pulled down in another dip as he tries to cope with crazy Quint, who at one point even smashes the boat’s radio.

The plot goes into fever pitch after this, with dips and rises as they chase the shark. The STAKES ARE RAISED as their weapons prove futile, and the boat starts to fall apart and the shark even starts to gnaw on it.

We’re entered the final big trough when Hooper decides the only option left is for him to go down in the shark cage. (STAKES ARE RAISED AGAIN). Hooper disappears, presumed dead. And then we begin the final plunge into the abyss for poor Brody. Quint goes out in a blaze of gory…

And there is our hero, alone on a sinking ship, staring into the maw of death. Which brings us to one of the most effective ways to beef up your plot — ISOLATION OF THE HERO. Think of Clarise Starling alone in that creepy basement. We’ve use this device often, putting our hero Louis in abandoned asylum tunnels, on frozen ice bridges on Lake Huron, gator-infested Everglades, and yes, on a sinking boat in the Gulf. It gives your hero that final chance to prove himself — through guts and brains — and triumph over evil. Remember how Brody did it?

Blasted the bad guy to bits. With his final bullet. And he couldn’t even swim. What a guy. What a climax. What a roller coaster ride.

One last note: In the book, Peter Benchley lets the shark just swim away never to be seen again. Which is a really really bad ending. But that is a blog for another day.

Fire up Your Fiction with Foreshadowing

by Jodie Renner, editor, author, speaker

by Jodie Renner, editor, author, speaker

To create a page-turner that sells and gets great reviews, be sure to keep your readers curious and worried throughout your novel. That will keep them turning the pages. You can add tension, suspense, and intrigue to your story very effectively with techniques like foreshadowing, withholding or delaying information, stretching out the tension, and using epiphanies and revelations. (All discussed at length in my book Writing a Killer Thriller.)

Foreshadowing is about sprinkling in subtle little hints and clues as you go along about possible revelations, complications, and trouble to come. It incites curiosity, anticipation, and worry in the readers, which is exactly what you want. So to pique the readers’ interest and keep them absorbed, be sure to continually hint at dangers lurking ahead.

Use foreshadowing to lay the groundwork for future tension, to tantalize readers about upcoming critical scenes, confrontations or developments, major changes or reversals, character transformations, or secrets to be revealed.

Foreshadowing is great for revealing character traits, flaws, phobias, weaknesses, and secrets; building character motivations; and increasing reader engagement.

Foreshadowing also adds credibility and continuity to your plot. If events and changes are foreshadowed, then when they do occur, they seem more believable and natural, not just a random act or something you suddenly decided to stick in there. For example, if your forty-something, somewhat bumbling detective suddenly starts using Taekwondo to defeat his opponent, you’d better have mentioned at some point earlier that he has taken Taekwondo lessons, or else the readers are going to say, “Oh, come on! Give me a break. Suddenly he’s Jackie Chan?”

But for every hint you drop, make sure you follow through later in the novel. Be sure not to drop in what seems like a critical piece of info or object, but ends up not foreshadowing anything. Readers will feel deceived and cheated. (For more on this, Google “Chekhov’s gun” or see my book.)

Also, do be subtle about your little hints. If you make them too obvious, it takes away the suspense and intrigue, along with the reader’s satisfaction at trying to figure everything out.

Some ideas for foreshadowing:

Here are some ways you can foreshadow events or revelations in your story:

– Show a pre-scene or mini-example of what happens in a big way later, for example:

The roads are icy and the car starts to skid but the driver manages to get it under control and continues driving, a little shaken and nervous. This initial near-miss plants worry in the reader’s mind. Then later a truck comes barreling toward him and…

– The protagonist overhears snippets of conversation or gossip and tries to piece it all together, but it doesn’t all make sense until later.

– Hint at shameful secrets or painful memories your protagonist has been hiding, trying to forget about.

– Something on the news warns of possible danger – a storm brewing, a convict who’s escaped from prison, a killer on the loose, a series of bank robberies, etc.

– Your main character notices and wonders about other characters’ unusual or suspicious actions, reactions, tone of voice, facial expressions, or body language. Another character is acting evasive or looks preoccupied, nervous, apprehensive, or tense.

– Show us the protagonist’s inner fears or suspicions. Then the readers start worrying that what the character is anxious about may happen.

– Use setting details and word choices to create an ominous mood. A storm is brewing, or fog or a snowstorm makes it impossible to see any distance ahead, or…?

– The protagonist or a loved one has a disturbing dream or premonition.

– A fortune teller or horoscope foretells trouble ahead.

– Make the ordinary seem ominous, or plant something out of place in a scene. Zoom in on an otherwise benign object, like that bicycle lying in the sidewalk, the single child’s shoe in the alley, the half-eaten breakfast, etc., to create a sense of unease.

– Use objects: your character is looking for something in a drawer and pushes aside a loaded gun. Or a knife, scissors, or other dangerous object or poisonous substance is lying around within reach of children or an assailant.

– Use symbolism, like a broken mirror, a dead bird, a lost kitten, or…

~ A no-no about foreshadowing:

But don’t step in as the author giving an aside to the readers, like “When she woke up that morning, she had no idea it would turn out to be the worst day of her life.” We’re in the heroine’s head at that moment, and since she has no idea how the day is going to turn out, it’s breaking the spell, the fictive dream for us to pass out of her body and her time frame to jump ahead and read the future.

~ Don’t like to plan your story out first? Just go ahead and write your story, then work backward and foreshadow later.

If you hate to outline and just want to start writing and see where the characters and story take you, you can always go back through your manuscript later and plant clues and indications here and there to hint at major reversals and critical events. Doing this will not only increase the suspense and intrigue but will also improve the overall credibility and unity of your story.

And remember to sprinkle in the foreshadowing like a strong spice – not too much and not too little. If you give too many hints, you’ll erode your suspense. If you don’t give enough, readers might feel a bit cheated or manipulated when something unexpected happens, especially if it’s a huge twist or surprise.

And again, the operative word is subtle. Don’t hit readers over the head with it. Not all your readers will pick up on these little hints, and that’s okay. It makes the ones who do feel all the more clever.

For more techniques for adding conflict, tension, suspense, and intrigue to any genre of fiction, check out Jodie’s book, Writing a Killer Thriller.

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources to date: Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage. You can find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, her blog, http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/, and on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.

A Short Course on Dialogue Attributions

If one character uses the name of the other character, for emphasis, you can break up the dialogue this way:

Oops!

Reader Friday: Hunting for the Right Word

The Historical Research of Heroic Measures–Guest Jo-Ann Power

Jordan Dane

@JordanDane

I’m very pleased to have my guest, Jo-Ann Power, at the Kill Zone today. Her new novel involved historical research of WWII that I thought you might find interesting. I’ve bought the book for my mom who always talks about her teens years as “Rosie the riveter” during the war effort. This historical period has been fascinating to me. Enjoy and take it away, Jo-Ann.

Grateful to be a guest here at TKZ, I know the importance of solid research for any kind of fiction. Having written a few mysteries and many historicals, I know the value of fact as the bedrock of any entertainment for readers.

For HEROIC MEASURES, my novel about American nurses serving on the front lines in France during the Great War, I did research that led me to many of the same resources that many writers use. First, I read general histories for an overview of the conflict. Then I haunted the stacks of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. and the National Archives for weeks on end. Newspapers from those years plus nurses’ letters, diaries and photos gave me tiny facts that provided not only color but an accuracy obscured by general histories.

Next I went to Army facilities like Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania where the Army keeps its repositories of memorabilia of soldiers and nurses who served in that first global conflict. I traveled to Cantigny in Wheaton Illinois where curators there pulled primary and secondary documents from their collection of recruits who served in the First Division of the American Expeditionary Forces.

My longest (and most delightful) excursion was to France. For three weeks, I walked the front lines of our American soldiers in northern France. I visited the battle lines, overgrown with moss and grass but many still pock-marked with fox holes and shell holes. I saw the terrain our soldiers fought through. The wide plains of farmland they ran through. The woods where they drew their bayonets and fell into hand-to-hand combat. I saw the territory where peaceful rivers now run and understood by viewing the terrain why keeping control of this river or that mountain was vital to the defense of a town, a section of the land or Paris, itself.

I talked with the curators of those museums, the people who live there and tell tales of their ancestors who lived there at the time. I discussed the valor of nurses and YMCA workers, Salvation Army volunteers and ambulance drivers. I walked the pristine rows of American cemeteries where the remains of more than 40,000 of our American men and women lie in testament to their devotion.

What did I learn in those trips? I learned about the weather in the spring time in France. Wet and cold. Just as it was so very often during the four years of war. I learned about the fertility of the Champagne and Lorraine regions. The area then was rich: today France grows 20% of the produce for European Union. I saw the importance of the City of Verdun. Nestled in the mountains, this city is the main route for two rivers. Control this city and the victor controls the major water route to Paris. I experienced the diversity of culture in the Alsace where many speak not only French, but English and German. I heard from them how they intermarried, and I could understand how they had to divide their loyalties and how difficult that was one hundred years ago.

I also learned from our American directors of our cemeteries that very few Americans come to these hallowed grounds to pay their respects. Most travel to Normandy, remembering the valor of those who took the beach in 1944. But in the coming five years, I hope you will remember the valor of the first group of Americans who went to serve and suffer and fight in Europe. I hope you will rent a car at the Paris airport and head into the Champagne, not merely to drink the best bubbly you will ever enjoy, but to visit these cemeteries, talk to the staff and ask them about the valor of these first American adventurers. They have stories to tell.

Mine is fictitious. But based in fact.

Here is one woman’s story of her journey from her small hometown to the greater world. I hope you enjoy HEROIC MEASURES.

For more on American nurses, read Jo-Ann’s HEROIC MEASURES blog: http://theyalsofought.blogspot.com

For the purposes of discussion at TKZ, how far have you gone for research and authenticity in your writing? Are any of you writing a period piece involving historical research? If you are, tell us about the challenges.

How heroic are you? Would you volunteer to travel thousands of miles from home with others you don’t know to live in tents, wash your hair in your helmet and work 12-24 hours each day?

In the Great War, thousands of women did. HEROIC MEASURES is the novel that shows you how American nurses went to war, how they lived and served—and how they loved.

For nurse Gwen Spencer, fighting battles is nothing new. An orphan sent to live with a vengeful aunt, Gwen picked coal and scrubbed floors to earn a living. But when she decides to become a nurse, she steps outside the boundaries of her aunt’s demands…and into a world of her own making.

Leaving her hometown for France, she helps doctors mend thousands of brutally injured Doughboys under primitive conditions. Amid the chaos, she volunteers to go ever forward to the front lines. Braving bombings and the madness of men crazed by the hell of war, she is stunned to discover one man she can love. A man she can share her life with.

But in the insanity and bloodshed she learns the measures of her own desires. Dare she attempt to become a woman of accomplishment? Or has looking into the face of war and death given her the courage to live her life to the fullest?

HEROIC MEASURES BUY links: Amazon digital, Amazon print, Barnes and Noble, Kobo, iTunes, Allromanceebooks.com, Wild Rose Press

Bad Boy, Whatcha Gonna Do?

By Joe Moore

If I asked you to name 5 of your favorite heroes and 5 villains, which would you think of first? Which would come easier, the good guys or the bad? If you’re an action-adventure fan and you read a lot of Clive Cussler novels, Dirk Pitt would probably pop into your head right away. Now, name one arch-villain in a Dirk Pitt novel. We all know or have heard of Jack Ryan, Jason Bourne and Lara Croft. But name the bad guys they fought against. The reason it’s harder to recall specific villains is because it’s harder to write memorable bad guys. There aren’t that many Hannibal Lecters out there. But there are quite a few Clarice Starlings.

If you’re working on making your villain memorable, here are a few tips to do so.

Your villain must have multiple layers, perhaps even more that your hero. Stereotypical 2-D villains are boring. Why? Because we’ve all seen our share of non-motivated antagonists. A bunch of teens go to a cabin by a lake and start getting chopped up one by one. Seen that before? The villain is a killing machine. Why? Most of the time we have no idea. How about a good guy who turns bad. The motivational layers are all there. Just watch BREAKING BAD or DEATH WISH.

Your villain must be intelligent. Perhaps even more so than your hero. The brilliant bad guys are the ones that make the hero work really hard to solve the conflict. Their meticulous planning and concentration make them memorable. To see a brilliant villain in action, watch DIE HARD or SPEED.

Your villain had to have baggage. Preferably enough to make the reader cheer for him at least once. This usually happens near the beginning of the story where we see what motivates him. There is a hint of sympathy from the reader. But it doesn’t last long. Mr. Villain does something nasty and the sympathy shifts to the protagonist.

Your villain must face a fork in the road—a point in the story when he chooses to become a bad boy. The reader must believe the choice was voluntary. No one is born evil. They must choose to become evil somewhere along the way, for a believable reason.

Most important of all, your villain must be convinced he’s right. He needs to believe that his course of action is the correct path. Whether it’s revenge or jealousy, or some other strong motivator, he must do what he does out of commitment to being right. He must believe it and so must the reader.

As you write your villain into your manuscript, remember that he is not a throwaway character. He must be accepted by the reader for what he stands for and what he believes. For most of your story, he has to be as strong a character, if not stronger, than your protag. Make him memorable.

Now your turn. Name 5 of your favorite heroes and five villains your love to hate.